The artist and performer tore up cultural hierarchies not just as a form of political activism but as a way of making sense of who he really was

In 1980, a nineteen-year-old Leigh Bowery escaped his conservative middle-class Christian upbringing in suburban Melbourne to follow the scent of the punk and New Romantic scenes in London. Within five years he’d launched the club night Taboo in Leicester Square, which in its brief, 18-month existence developed a reputation as a raucous epicentre of queer culture. He was as beloved by the owners of Brick Lane and Southall fabric shops (from whom he bought metres of fabric on the cheap for his various nighttime costumes) as he was by British painter Lucian Freud, with whom he sparred intellectually, and for whom he became a prominent muse in the years before his death at the age of thirty-three from complications related to AIDS. Fragment of Head of Leigh (1993/94), a large painting by Freud in Tate Modern’s new exhibition Leigh Bowery!, shows Bowery from above as he lies supine; unfinished, with the exposed canvas and pencil lines still visible, it’s as if both painter and sitter ran out of time.

Early on in his London life, Bowery modified his accent and speech delivery to assimilate the local club kid inner-sanctum drawl (captured in Charles Atlas’s 1986 film, Hail the New Puritan), such that many of his friends didn’t realise he was Australian. In diary entries from the time displayed in vitrines at Tate, he questions his image, invoking Jean Cocteau and Sigmund Freud, and begins to make a fiction of himself. We learn that he constructed an inner life for himself in which he was taken to Harrods as a boy, while in a 1988 episode of BBC1’s The Clothes Show, Bowery brought this fiction to life when he appeared with a cut-glass English accent, swirling around the Harrods tea room in sequinned frills. Personally polite in private conversation with friends and strangers alike, he was publicly provocative. He named one garment collection ‘P*ki from Outer Space’ and sewed a quilt out of Lucian Freud’s old paint rags (Freud being Jewish) in which the face of Hitler can be seen. He palmed back questions regarding his use of a (reverse) swastika as a makeup motif, explaining that it originated as a Hindu peace symbol. Which is true, but still. Despite warnings from Les Child, a black collaborator and friend, he more than once adopted minstrelsy. Coming from a socially conservative background, he well knew how to shock mainstream society, and his ‘provocations’ can be seen less as an attack on marginalised groups and more an absurdist theatre of shock values. Perhaps he wanted to shock himself out of his own complacency, and to tear down anything he’d been taught by society to believe was sacrosanct.

Several of American director John Waters’s early films depict teenagers rebelling against their conservative parents and by extension the wider status quo, and Bowery was shown the way when he first saw Female Trouble (1974) just a few months after arriving in London. Female Trouble – for me a key text in understanding Bowery’s point of view – stars Baltimore-born drag queen Divine (who, like Bowery, came from a conservative middle-class family) as Dawn Davenport, a teenage runaway whose delusions of wealth, fame and beauty are enabled, catastrophically, by a high society couple who see in her an opportunity to create art. I remember watching Female Trouble on my first day in London back in 2004. The film’s melodramatic questioning of morality and perversity radicalised me to the extent that, later that July day, I accepted for the first time an offer of money in exchange for sex. I put my own body on the line in an act of rebellion against my Christian upbringing, making myself abject in search of self-knowledge. I wanted to be made physically uncomfortable, and felt drawn to the wilful bodily transgressions of the Viennese Actionists; the artist Paul McCarthy’s psychosexual ‘fluid’ videos and live performances, in which he is smeared with ketchup, mayonnaise and shit; the darkly confrontational live shows of Throbbing Gristle; Jean Genet’s ruthless pursuit of the beauty of evil in Our Lady of the Flowers (featuring a fictionalised alter ego named Divine). I wanted to be where I should not, doing forbidden things.

With the same inspiration, Bowery went out, shyly at first, and made garments to dress himself in, because he grew to understand the power of his imposing physical presence – fleshy, and well over six feet in his heeled boots – and how a unique look can make an immediate, indelible impression. He became an overt performer in all aspects of life, developing excellent comic timing and physical comedy skills in the live stage shows he would present primarily within the underbelly of London’s thriving queer nightlife. In the exhibition we see PP Hartnett’s polaroids of Taboo regulars, in which only glimpses of its interior space (chosen by Bowery and his business partner Tony Gordon because of its throwback late-70s tackiness) can be seen, although I would have preferred an immersive recreation. We do, however, get working toilets (always welcome at the midpoint in a multiroom show), and apt as Bowery was a champion cruiser. They are, at least superficially, modelled after those at Taboo, which Bowery in one of his blue ink-drip looks was photographed loitering outside of in 1986. (Here the toilets are pristinely white and functional, even when the opportunity presented itself to recreate the yellowy grime of a 1980s basement club toilet, complete with thudding beats. Going in, I felt disabused of the fantasy the exhibition was working so hard to create.)

Post-Taboo, Bowery made himself the event at other now-legendary London club nights such as Kinky Gerlinky, drawing eyes from everywhere. As a childhood Christian, he might have heard the apostle Paul’s exhortation in the Bible to ‘become all things to all people’, and instead injected his larger-than-life persona with an infectiously anarchic resistance to everyday norms. Of all, he championed through his unmissable appearance a politically charged queer visibility that was particularly polarising in a decade dominated by the AIDS crisis, widespread homophobia and, in the UK at least, Section 28, which prohibited the teaching or publishing of material with the intention of promoting homosexuality.

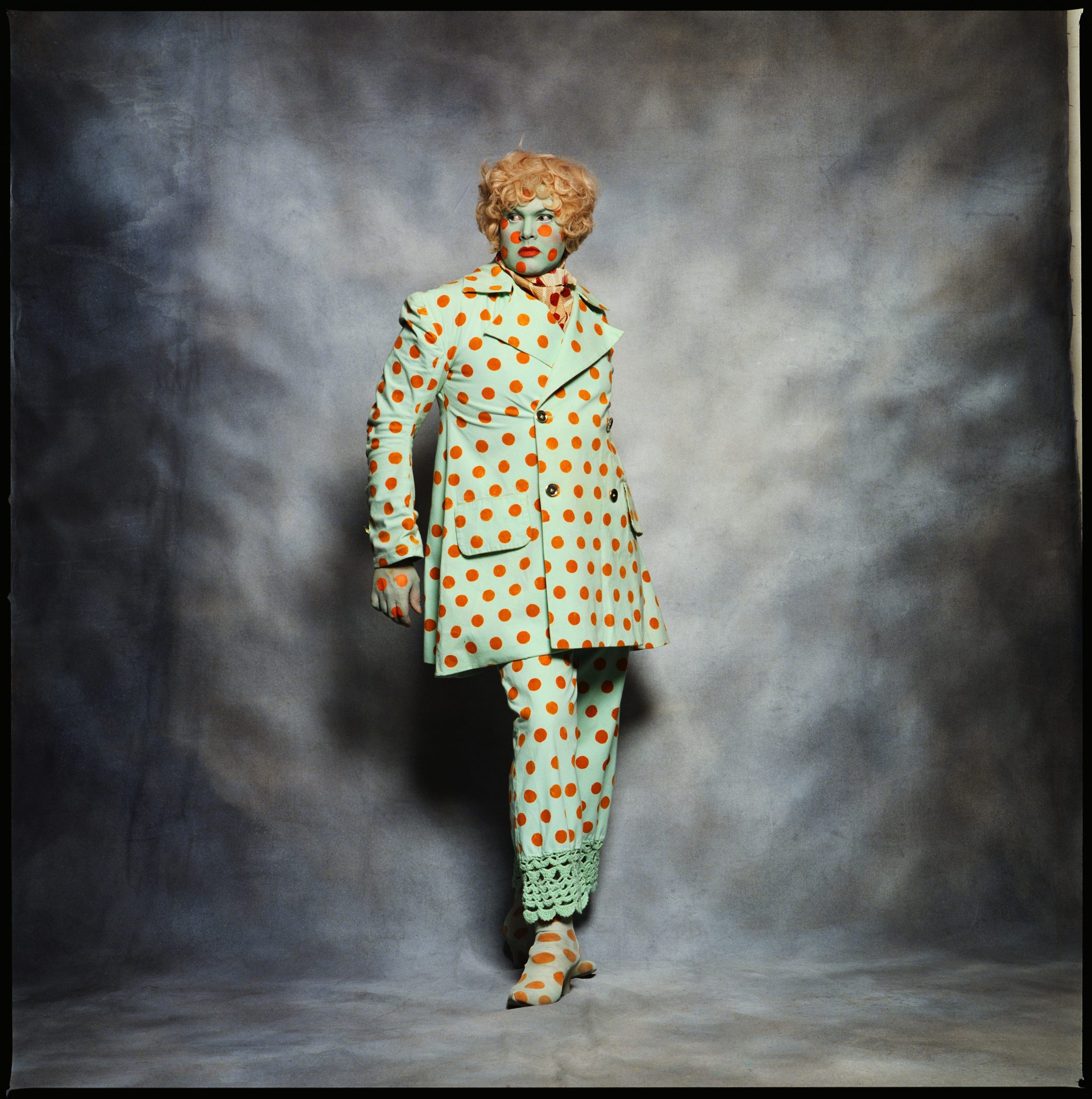

While his costumes (displayed on mannequins) and videos of performances comprise the main archive on display at Tate, also on show are works by Freud, the conceptual artist Stephen Willats, choreographer Michael Clark, filmmaker and artist John Maybury and Manchester postpunk band The Fall, many of whom Bowery directly inspired. He took codes from the perceived lowbrow cultures of exploitation cinema, maquillage and stage costumery into a high art realm, and in so doing tore up such cultural hierarchies not just as a form of political activism but as a way of making sense of who he himself really was. In live performances at Anthony d’Offay Gallery staged in 1988, Bowery appeared behind a one-way mirror that allowed the public to watch his every move while he instead saw only his reflection; he performed gently for himself for two hours each night in a different catalogued ‘look’. It is this tension in Bowery’s performative work, between self-knowledge and public provocation, that continues to make him such a compelling subject to observe. He morphed and distorted his body, often painfully and for many hours, with restrictive bindings, glues and piercings (though, notably, no tattoos, in what could be seen as a reflection of his unwavering commitment to the perpetual transformation of the self). Piercing his cheeks (so that he could wear plastic lips) helped him reclaim his body as his own, as something that belonged to and was fully accessible to him, rather than something ‘owned by [his] parents or the state’, as he wrote in one diary entry; he subjected himself to pain as a form of liberatory resistance to the strictures imposed upon him by others.

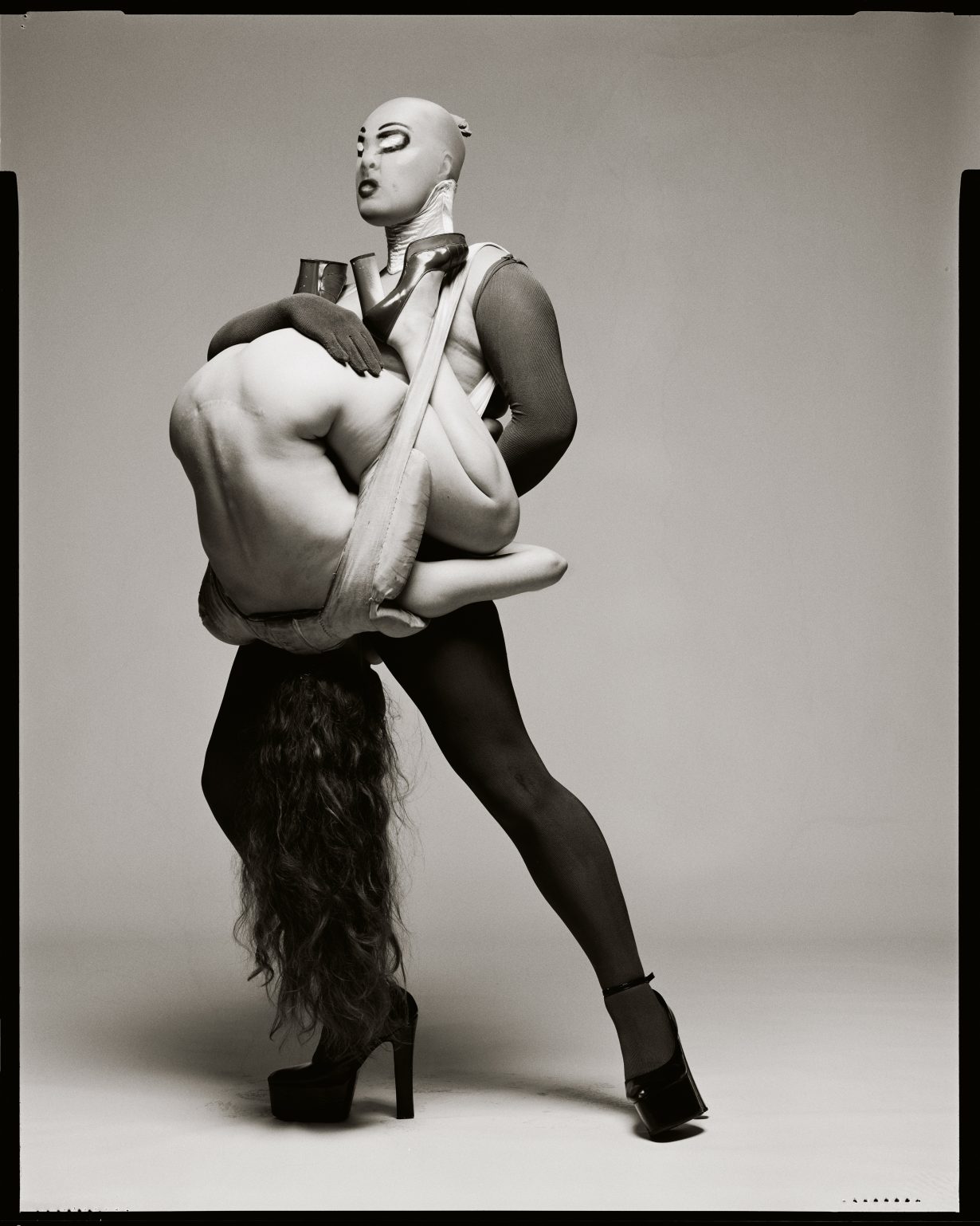

Perhaps the most painful ritual a human body routinely undergoes is childbirth, and even if Bowery (not possessing a uterus) could never facilitate a live birth, carrying the (admittedly petite) Nicola Rainbird, his best friend and later his wife, around on his torso for the duration of a musical number, while dancing and singing, at least showed his commitment to understanding the gendered nature of this pain, beyond the gag of it all. In the first of these ‘Birth’ performances, at Kinky Gerlinky in London in 1992, he wore a striped jersey dress, headscarf and sunglasses (identical to Dawn Davenport) before ‘giving birth’ to a naked Rainbird covered in red paint, who burst through his costume as he lay back simulating labour, and tearing through an umbilical chain of sausages with his teeth (in another reference to Female Trouble). The birth was later incorporated into the live act of his electronic music group Minty, for whom Rainbird, once ‘born’, would sing backing vocals. The final room of the exhibition is given solely to various of Bowery’s birth performances in London and New York, and their ephemera, including his final show at Freedom Café in Soho on 24 November 1994, five weeks before his death. Seen in the audience at this show is a young Alexander (Lee) McQueen, whose future collections bore the hallmark of Bowery’s shapeshifting, theatrical influence.

While self-identified as a gay man, Bowery had a fascination with women’s bodies. Sue Tilley recalls in her 1997 biography Bowery possessing a drawing of Saartje Bartmann (also known, pejoratively, as Hottentot Venus) on his workroom wall, for inspiration. Saartje was a South African woman with large buttocks (as is typical of her Khoekhoe community), but judged as shockingly warped and deformed according to the Western gaze. She was kidnapped and brought to Europe in 1810, where she was placed naked on public display to be gawped at in freak shows, mocked and sexually objectified. Experiments were performed on her body, and she eventually died penniless as a prostitute in Paris. Perhaps Bowery saw himself both as Saartje and as anatomist, at once the ‘freakish’ subject and the showman. Yet in his greater authority and control over his body, he knew how to display it and how it should be read (notwithstanding the AIDS virus, which he hid from even his closest friends and family, including Rainbird, until days before his death). That absolute control is evident in both Bowery’s live performances and the photographic portraits in which he starred, whether he is fully covered up, or covering up everything but what should normally be covered up; where he is fully nude, and where his body is completely absent. At Tate, a number of his garments are left conspicuously empty upon the gallery floor, in a recreation of a series of photographs by Bowery where his costumes (already damaged by the grime of the nightclub floors he so loved rolling around on) are thrown over a balcony to the street below. Perhaps he was already looking forward to a time where his work would have to exist without his physical presence.

In the 1980s, when Bowery discovered he was seropositive, life would have been about how much he could pack into it, and he went into overdrive as a creative performer and artist. He died on New Year’s Eve 1994 – just over a year before protease inhibitors, which slow the pace of viral replication, were made widely available – having left an indelible legacy on the worlds of art, fashion and club culture. It is a legacy that continues to morph and deepen as a new generation of club kids and artists discover Bowery’s life and work, although the presence at Tate Modern of this exhibition only after his death raises the question of how and why queer culture is archived in institutions only in retrospect, and usually in memoriam. His survivors from the queer London club scene of the 1980s include people I myself have danced with and to (Princess Julia and Jeffrey Hinton remain key London nightlife figures), in a through line between the scenes of then and now. They and many others feature in Leigh’s Lounge, Robert Fox and Josh Quinton’s playful documentary film that accompanies the exhibition, which revels in Bowery’s Warholian obsession with popular media and gossip. The looming public caricature of Bowery – confected in part by the artist, whose greatest work of art was arguably himself – makes an exhibition such as this, which pieces together much of what he created and inspired, key to humanising the myth.

Mendez is the author of Rainbow Milk (2020)