Culinary experiences in the artworld are on the rise, but why does food need to be framed as ‘art’ in order to be considered something special?

A bright green foam sits in the bowl; a couple of tanned potato chips are tucked tastefully to the side. Digging beneath the mostly tasteless foam (a bare hint of grassy sweetness suggests it’s made of pea) with a chip, you excavate a mound of salty ground-meat. The cumulative effect is reminiscent of the trashy hardshell tacos I ate in volume as a kid; but this, we’ve been told, is a food portrait of Claude Cahun and her partner Marcel Moore as ‘a shepherd’s pie – but deconstructed’. It is the third course in artist Sandra Knecht’s art-meal-event The Dinner Party (taking its name from Judy Chicago’s 1974–79 installation), staged at the Serpentine’s Magazine restaurant in London this past March. It’s one of a series of ‘culinary gatherings with a critical edge’ presented by the artist. Each of the meal’s eight courses presents a synaesthetic conjuring of figures who inspired Knecht, from musician PJ Harvey to artists such as Nan Goldin. The extended meal was filled with awkward chat, some tasty mouthfuls and a few delicious but oddly tasteless conceptual culinary choices: Frida Kahlo ‘as’ a chicken taco, Zanele Muholi ‘as’ vanilla ice cream.

Though by the time it all ended, what stuck out most was the repeated ‘deconstruction’ of many of the dishes. A nod, presumably, to the El Bulli-style mode of high-end cuisine, which seeks to elevate food by breaking down and altering its constituent parts. And perhaps, given that the event took place under the label of ‘art’, to the philosophical inclinations of thinkers such as Jacques Derrida. As if it wasn’t enough that it be a series of food portraits, but needed more. Although all that might have been affected by the slight buzz from the deconstructed Manhattan (Carson McCullers) with which the meal ended.

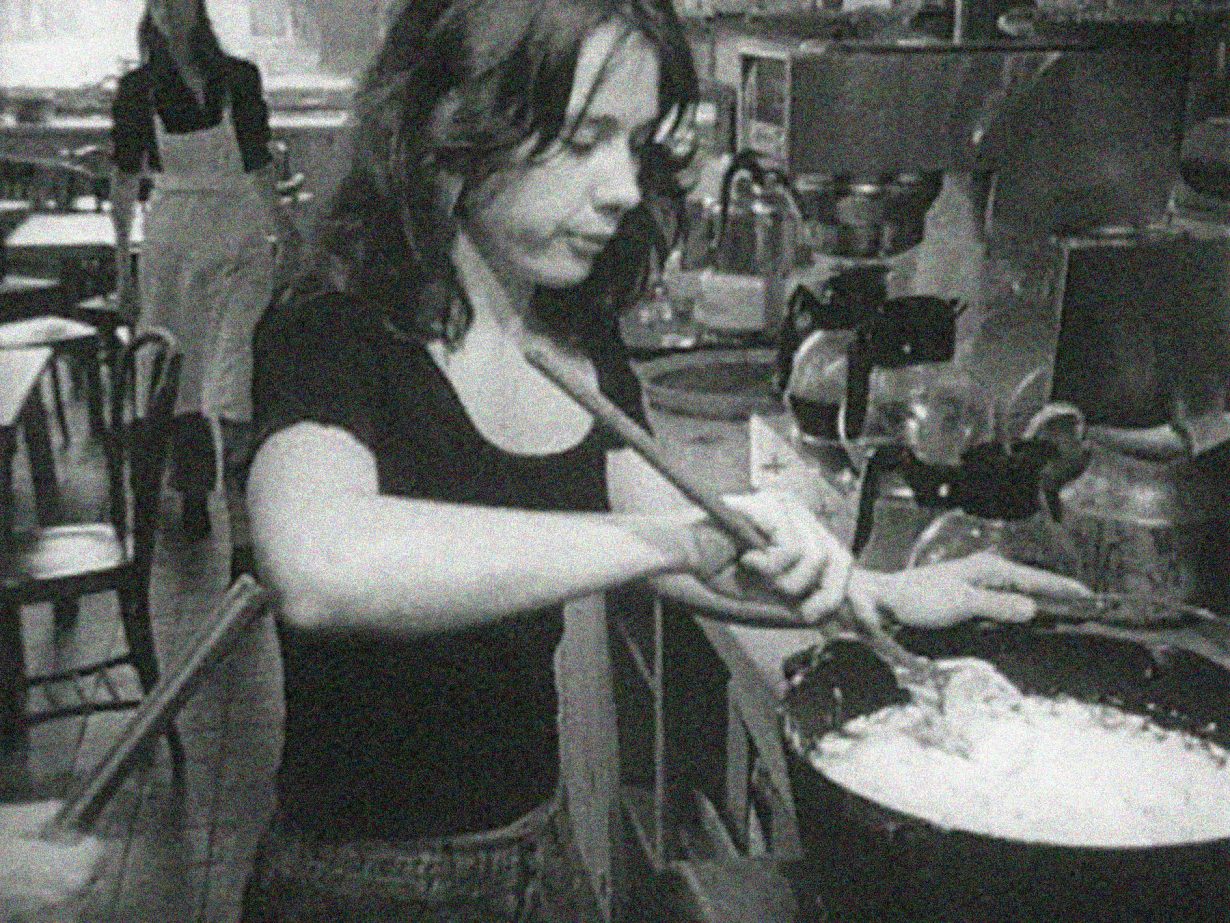

Food has often been on the table, as it were, at exhibitions recently. In the microcosm that is London alone there have been over half a dozen shows featuring food and art ‘culinary experiences’ in recent months. Ellen Mara De Wachter’s book More Than the Eyes: Art, Food and the Senses, released last December, positions food’s use in art as part of a shift away from the primacy of sight. ‘Working with food was, and still is, an unusual approach to making art,’ De Wachter tells us. The book offers a primer, profiling ten artists’ projects with food, from Carolee Schneemann’s Meat Joy (1964) to Tina Girouard, Carol Goodden and Gordon Matta-Clark’s FOOD restaurant (1971–74); though, given De Wachter’s selection, readers might get the impression that art and food was a combination cooked up only in late-twentieth-century New York City. (Right on cue, food is currently being reprised by artist Lucien Smith in NYC’s Chinatown.)

‘Artistic valorisations of the culinary are best taken with a grain of salt,’ warned writer and curator David Teh in the catalogue for the 2012 survey exhibition Feast, at the Smart Museum of Art, Chicago. Part of me wonders if it’s primarily an urban, art-centre fabulation: that food, and such gustatory events, are part of any practice and art scene, and simply aren’t packaged or marketed so overtly or extravagantly in less stratified, commodified and hierarchic locales. We choose not to see the food already involved with art (stale croissants sold at art-centre cafés; salted almonds furtively munched while wandering around a gallery; the glorifying pint and noodles sought mid-gallery run; the corner-store samosa grabbed before an opening; the flat supermarket sandwiches and crisps rushed mid-install; conspiratorial shared dinners with art friends; inane, unsatisfying opening-night dinners for those tangentially involved in an exhibition; the digestive biscuits eaten while writing this) as art food, in part because such consumptions could be part of anyone’s daily life. And, as such, they are apparently not sufficiently elevated to be placed on art’s table of contents.

But food’s always been a means, fuel or subject for art, at least since someone etched some plants and animals onto a cave wall thousands of years ago. Like sound, food is a slippery ur-media that art can embrace but can’t control: material and utilitarian, multisensory and loaded with histories and ideas, social and immersive, it can slip in and out of any arena and spill all over your shirt. It’s already its own concept and context. Food is art, great. So why does it need to be constantly reframed as something transgressive or new to art?

Perhaps it’s not a question of medium but of what is lost when food is recontextualised in the art gallery or institution, where it’s then expected to carry the weighty baggage of expectation as a novelty and boundary breaker. In his speech introducing Knecht’s event, Serpentine artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist mentioned the artist’s farm in Switzerland as an example of a ‘durational’ artwork, alongside those farms of other artists, such as Yinka Shonibare and Adrián Villar Rojas. Meanwhile, collectives such as Campo Adentro in Spain, Sakiya in Palestine or Lakshmi Nivas Collective in India are exploring the merging of art practices with agriculture and pastoral practices. Such endeavours seem geared not towards filling high-end tables, but rearranging systems of production, distribution and living. Growing food and making food are inherently communal ecological acts, political and relational. Sharing food and eating it is too – but sometimes less so. Perhaps if there’s any use to coopting food into an art context, it’s to foreground these relationships and issues. To be seated at a dinner-as-art, though, one doesn’t always feel so conscious or critical, making small talk while waiting for dessert. At that point, the art-meal’s proximity to high-end cuisine feels a little more uneasy, where we risk becoming not an art lover, just another delighted, lip-smacking gourmand.

The added layer of making exhibitions and installations about these facts is, more often than not, sterile, confusing and misguided, if not exclusionary and creepily insidery. I often think of the widely distributed imagery of Cooking Sections’s ongoing CLIMAVORE project (2017–) on the Isle of Skye, of a small group of people having a meal on a set of benches and tables made of oyster cages set in a bay’s water at low tide. I’m sure it was a lovely experience for those who were there; but if a meal is the project, exhibiting documentation of the meal is just gloating. Knecht’s inspirational meal in London was open seating at long tables for dozens of people to mix, and at £24 a head, relatively accessible – but it was also set on a March weekend daytime during Ramadan, the timing swiftly framing who in the city is welcome at the table.

The point isn’t that such events shouldn’t happen, but that they should be more proliferative and less fawned over. It doesn’t need any further deconstructing: food is already art, with or without anyone’s claims on it as such. The issues raised and at stake aren’t special, but something quotidian instead, issues taking place already, at your table.

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.