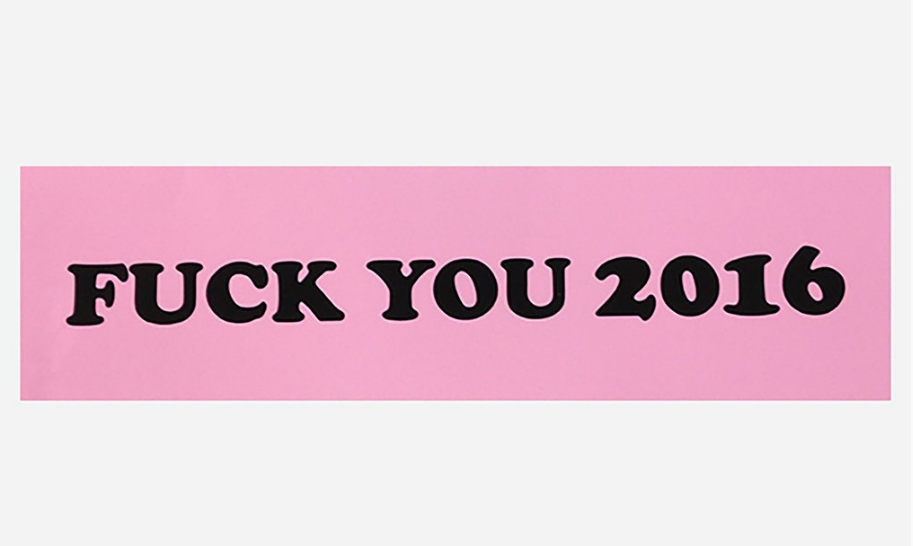

‘FUCK YOU 2016!’ The sentiment of UK artist Jeremy Deller’s bumper sticker (made for a fundraising show of artist’s works and editions at London’s House of Voltaire) pretty much sums up much of the artworld’s feelings about a year of global chaos, political upheaval and cultural antagonism. A year of Brexit and Trump, of chaos in the Middle East, of carnage on the streets of Europe. In the face of all this, the world of contemporary art found itself feeling frail and impotent, staggered by the apparently unstoppable rise of the ugly opposite of all it holds dear – intolerance over openness, nationalism, xenophobia and closed borders over internationalism and free movement, racism over multiculturalism, misogyny, homophobia and gender conservatism against the pluralism of feminism, gay rights and trans activism. In short, the rise of everything bad against everything good.

But the sense of confusion and panic among some, particularly in response to Donald Trump’s election, suggests that it’s time the artworld starts thinking a bit harder about where it sits in the bigger picture of politics and society. In a shrill and somewhat deranged editorial in January’s Frieze, co-editor (and New York resident) Dan Fox accuses anyone of having voted for Trump of helping ‘to commit an act of mental violence on millions’, blaming artworld Trump voters (‘I’ll bet there are a few of you lurking in the art world’) for the distress ‘you have helped visit upon every friend, colleague or member of my community who… has wept, shaken with anger, hidden away in depression or dread… not because they are sore losers… but because they are female, black, brown, Muslim, queer, an immigrant or too poor to pay for medical care.’

Artworld people are too polite to point fingers, but those who aren’t part of ‘our community’ are really the ‘basket of deplorables’ who Hillary Clinton chose to condescend as ‘irredeemable’ during the US election campaign

Regardless of what one thinks of whether such emotive reactions are exaggerated or justifiable (trigger warning: I’m ‘white, aged 40, male, heterosexual, and raised a Christian’, just like Fox, so don’t believe anything I’m now going to say), Fox’s identification of ‘my community’ as, by default, the province of liberals and minorities, reveals a lot more about what artworld people presume about everyone else out there – all those ignorant, racist, sexist, mostly white, probably male, blue collar types who ‘lurk’, ‘out there’, outside the cities, in the American rustbelt or northern English towns or French provinces. Artworld people are too polite to point fingers, but those who aren’t part of ‘our community’ are really the ‘basket of deplorables’ who Hillary Clinton chose to condescend as ‘irredeemable’ during the US election campaign. As Clinton found out, insulting ordinary people doesn’t tend to encourage them to vote for you.

But what’s problematic about the too-easy alignment of the ‘art world’ with a caricatured version of good liberal minorities versus the bad conservative voting masses is the way it politicises art, turning it into a space which is nothing more than the reflection and extension of a particular political perspective. In 2016, that perspective has been characterised by a particular form of identity politics, particularly in the new wave of feminism, the politics of ethnicity typified by Black Lives Matter and the ferocious controversies that have raged around gender and sexual identity. If these have anything in common, it is their hostility to ‘normative’ culture, inevitably characterised as white, male and straight. The political consequences of these perspectives aren’t conducive to building solidarity among social groups, since they identify the problem as the existence of certain social groups and the cultural attitudes those are supposed to harbour. It’s a divisive politics, at a time where what progressive politics really needs is a confrontation of the problems people – whatever their ‘identities’ – face right now; austerity, failing living standards, stagnant economies, threats to free speech (which come in the form of self-censorship demanded by so-called progressives as a much as state censorship), and the widespread rejection of democracy when that democratic process produces a result you don’t agree with. But above all these, perhaps, is the biggest that other middle-aged white male Adam Curtis has sharply identified: the society-wide sense that politics can do little more than keep society stable in the present, rather that radically transform it for the better in the future. What’s for sure is that typifying others as stupid, racist, sexist, or whatever, because they happen to have given up on a liberal ideal of society that hasn’t delivered anything for them, is no way to bring people together to take on those challenges.

But that’s all political talk, and there’s plenty of it rattling around the artworld. So what about art in 2017? If art is worth anything, maybe its value lies in representing what hasn’t already been represented, in speculating on everything that is possible rather than the currently existing. ‘How should art, artists and the artworld respond?’ asks Fox. ‘You should know that it’s crucial to keep making art and to keep talking about culture and politics.’ Yes, but what kind of culture, and what kind of politics? If, in 2017, art isn’t to be merely the echo chamber for the identity politics of those who self-identify as the ‘art community’, it might have to imagine a wider horizon of what is possible, a more expansive sense of who its speaks to, who it speaks for, and what common future we might look to.