Opening the morning mail a few months back, I found myself holding something I never expected to see: an invitation to a ‘comprehensive’ Cady Noland retrospective, at the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK) in Frankfurt. I blinked. I inwardly called bullshit. Noland – who, if you don’t know her, is the American artist who most saliently and scathingly predicted the mess her country is currently in – has not exhibited any new work since 2000. After that, and specifically after dismantling her final artwork (for a group show at New York’s Team Gallery), destroying its parts and stowing them in bins around Manhattan, she effectively quit the artworld in disgust at its hypocrisies and inequalities. She made a couple of pieces in the following decade, but only to replace damaged ones. While a practising artist and after – the ‘after’ being mostly spent blocking exhibitions, denying authorship of works made by her that had parts missing, refusing to have her photograph taken, refusing to be interviewed and being generally obstreperous – she had never sanctioned a retrospective, despite offers from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, among others. In a rare conversation with Sarah Thornton in 2014, she’d allowed that she might permit such a thing further down the line. But even if she didn’t love MoMA (she’d called them out for sexism in the past), was it going to happen in Frankfurt? Nah. Someone there was cobbling together a few loans and calling it a survey. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

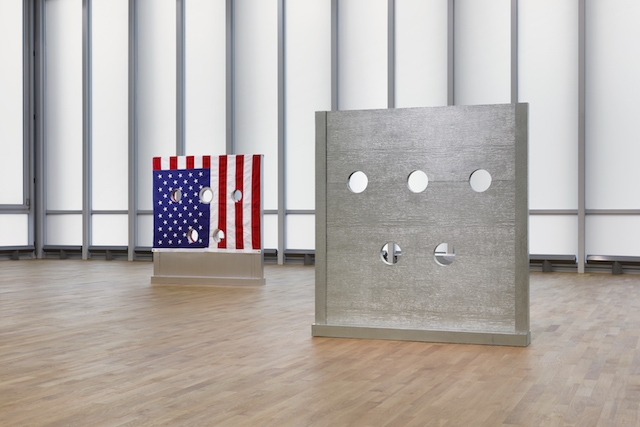

The show opened – it runs until the end of March – and images started turning up on Twitter and Instagram: signal examples, freshly exhumed and darkly sparkling, of Noland’s astringent, American-nightmare sculptural style: from menacing aluminium stocks waiting for victims to shopping baskets filled with hubcaps and firearms, to obscure 2D works that looked like restaurant logos but were blazoned with sardonic slogans like EAT YER FUCKIN FACE OFF!!! Goaded, I booked a train to Frankfurt and was confronted with, for a Noland fan, the outright ridiculous, the oh-my-stars. Eighty-four works from 1984 to 2008, three made in collaboration with the late Diana Balton, are distributed across three floors of the museum, at times spaciously positioned so that their kinaesthetic terrors and compositional smarts ring out, at others tucked away Easter-egg-style round corners and in alcoves. (According to the list of works in the accompanying booklet, a good number of these are owned by a figure you’d consider their maker’s antithesis: Larry Gagosian.)

In her 1989 essay ‘Towards a Metalanguage of Evil’, she compares entrepreneurial males and psychopaths, and analyses America as a land of barely suppressed violence, blunted by beer and voyeurism and racial and sexual enmity

Anyway, here are Noland classics like Oozewald (1989), an aluminium cutout image of Lee Harvey Oswald punctured with seven circular holes, schematic gunshot wounds, mouth plugged with a bunched-up American flag. Noland, like her painter-father Kenneth, gravitates to targets; and this work, sold at auction in 2011 for $6.6 million, made her the most expensive living female artist at the time. Here are signature assemblages that either spill their contents onto the floor like updated 1970s scatter works or contain them in consumerist frames like shopping trolleys and baskets, incorporating ephemera that seems to indict a whole culture: American celebrity magazines, weaponry, Budweiser cans, buckles, ammo, sunglasses, cameras, car polish. Here too, interspersed, are a choice handful of works by other artists, including fellow traveller Steven Parrino – whose crumpled canvases sync perfectly with Noland’s own sense of cultural ruination; Charlotte Posenenske; Joseph Beuys; and Andy Warhol, from whose Death and Disaster paintings much of Noland’s bleak, silvery mien clearly descends, as she herself cops to here. In her 1989 essay ‘Towards a Metalanguage of Evil’, she compares entrepreneurial males and psychopaths, and analyses America as a land of barely suppressed violence, blunted by beer and voyeurism and racial and sexual enmity; the exhibition testifies to this. It looks shockingly contemporary.

I wandered around half-stunned – and, in a very Noland moment, was temporarily turfed out when some kind of alarm sent the museum into a state of emergency – and then I came back, buzzed the museum’s director and the show’s curator, Susanne Pfeffer, from the desk and we sat down for a quick coffee. (And later conversed by email.) This was her first show since taking the post at the museum. How on earth had she managed this curatorial coup? Why was it here? The MMK, Pfeffer notes, had a good many works by Noland in their collection, thanks to a substantial gift from a collector. That and her understanding of Noland’s works as “extremely relevant to the present time” was the starting point, she said. “I thought now or never. Then I got hold of her telephone number” – a statement that elides this process taking a while, aided by a collector, a contact in New York and a building of trust – “I again studied her work intensively, and asked for a meeting. We met and she said yes.” More than just saying yes, Noland has been extremely hands-on with the show, from tinkering with elements of the display after the opening to personally selecting images for press coverage. “It was and still is a very intense and close collaboration,” says Pfeffer.

Noland may, after this outing, go back into seclusion, her overarching statement perfectly made, her position in art history that bit more assured

My mind made an odd connection. In 2014 the American R&B auteur D’Angelo released his first album since 2000, Black Messiah, evidently galvanised by Black Lives Matter. (On Twitter, I floated the wacky idea that this show was Noland’s equivalent: an art historian wrote back, ‘I have no idea what you mean, but I completely agree’.) To Pfeffer I wondered aloud if Noland had been similarly affected, in the decision to make this show, by current events – certainly the curator had – and whether the Frankfurt location, with Germany currently presenting some kind of relatively stable counterweight to America’s spiralling, had some deliberateness about it. While acknowledging, as if it needs saying, that “Noland’s work has always been highly political”, Pfeffer says she doesn’t know about that. The artist, apparently, is giving a lot to this show, but she’s not particularly speaking for it. Once again, she’s not doing interviews, or it seems so unlikely that she would that I didn’t even ask.

There are currently no plans for this show – which to me, if it’s not already obvious, was easily the best I saw last year, outpacing even the Bruce Nauman retrospective – to tour. If that’s the case, it’ll dismay transatlantic Noland-watchers but has her characteristic bloody-mindedness written all over it. There is no catalogue either, just the aforementioned modest booklet with an essay by heavyweight German theorist Diedrich Diederichsen. The aforementioned D’Angelo hasn’t released another record since his brief return; Noland may, after this outing, go back into seclusion, her overarching statement perfectly made, her position in art history that bit more assured. (For Pfeffer, it’s a landmark in her own profession; a friend of hers joked that, after this, ‘every artist will trust you’, and they should.) But if we don’t hear from Noland again for the foreseeable, we can feel lucky to have had this – a toxic cornucopia of chromed steel, bullets, barbecues, saddles, whitewall tyres and abundant ambient fear: the twenty-first century already known, and given form, in the twentieth.

Cady Noland is on view at the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK), Frankfurt, through 31 March