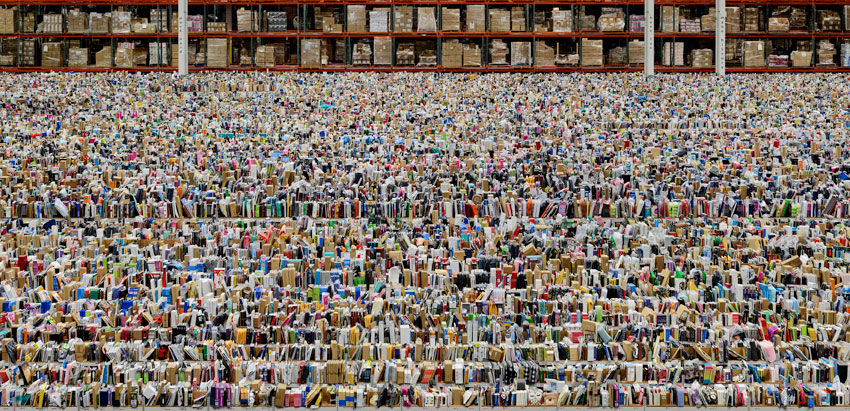

Andreas Gursky, Hayward Gallery, London, 25 January – 22 April

After a couple of years under wraps while renovating – included in that the restoration of 66 pyramidal glass skylights, formerly faulty and unusable, now allowing natural light into the building for the first time – the Hayward Gallery is reopening for its 50th anniversary. It’s doing so with a panorama of panoramas: a first UK retrospective for Andreas Gursky. The Leipzig-born artist has spent four decades working towards what he calls ‘the encyclopaedia of life’: visual evidence of the manmade in photographs that are huge, hyper-objective, panoptic and, in recent years, digitally adjusted. Some 60 works strong, Andreas Gursky will take viewers around this benighted world in a day (or couple of hours): stock exchanges to music festivals, 99-cent stores to planted fields, the 90,000sqm distribution centre in the candy-toned, product-dense Amazon (2016), the iconic empty shelving of Prada II (1997) to semifictionalised scenarios such as Review (2015), in which Angela Merkel and three former German chancellors sit before Barnett Newman’s huge Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1950–51). The artist’s ‘zips’, Gursky has said, here represent shifts in German political eras – abstract-looking images, as his own practice increasingly advocates, still stand for something. (Paging his dealer Larry Gagosian: an edition of Gursky’s oeuvre ought to be shot into space tout de suite, both as affirmation of human possibility and cry for help.)

Sam Keogh, Kerlin, Dublin, 27 January – 10 March

Somewhere up there, figuratively at least, is Sam Keogh, whose Kapton Cadaverine at Kerlin involves a grimy spaceship interior adorned with collages and sculptures. During the opening-night performance that, in a sense, activates these, an astronaut (Keogh) will emerge from his cryopod after a couple of years of suspended animation and engages with the nested creations; the scenario flipping between exploratory reorientation on a rocketeer’s part and tour of an artist’s studio, the accumulations either artworks or attempts to repair the ship. (Audio from the performance, recorded, will float over the installation for the rest of the show.) Keogh, who’s Irish himself, is interested in ‘how surface and texture can transmit narrative’, as was written in a press text for a 2016 show that used drawings under a floor of plastic sheeting, fleshy sculptural lumps and, again, a performative element to loosely consider the death of Gianni Versace. Looking back on Keogh’s earlier work – in 2012, he was making lumpy multicoloured sculptures intended as a kind of ‘species’ – what’s clear is a consistent commitment to art as processual: whatever the form, it’s in a constant, unstable state of becoming and modulation from without.

Ellen Gronemeyer, Anton Kern, New York, through 24 February

It may be that with reality fluxing so violently right now, metamorphosis is the new fixed. That’s the tenor one gets from Ellen Gronemeyer’s new paintings at Anton Kern. The Berlin-based German painter, who’s developed an out-of-time style that’s cartoonish and sour – at once mildewed in tone, grainy in texture and percolating with detail, full of round-faced child-adults and animals – here hangs up six new canvases featuring adults, children and pets either contemplating or, indeed, merging into each other. The works, we’re informed, ‘live off the contradictory energies of what is possible and what is imaginary’ – categories themselves that are unfixed; they pull us back to childhood, and childhood into adulthood. Gronemeyer’s works, murky at first but quick to get under the skin, may be, as fellow painter Daniel Richter opined in one interview about her work, ‘not zeitgeisty’, but that doesn’t mean they don’t suit the times.

New Museum Triennial, New Museum, New York, 13 February – 27 April

Unashamedly zeitgeisty and also in New York, meanwhile, is the fourth New Museum Triennial, subtitled Songs for Sabotage. Nothing to do with records by Black Sabbath or the Beastie Boys, the ‘sabotage’ here is rather a mooted process (a ‘call for action’, as the institution describes it) of engaging with media both new and traditional in order to illuminate how they fabricate, rather than mirror, our reality. This may sound like what artists do all the time; nevertheless, it’s gained urgency in an era of fake news, and the museum is being programmatic about the subject, inviting some 30 artists from 19 countries – the key issue being a global one – including a clutch of Americans but also Claudia Martínez Garay (Peru), Anupam Roy (Bengal), Zhenya Machneva (Russia) and Dalton Paula (Brazil).

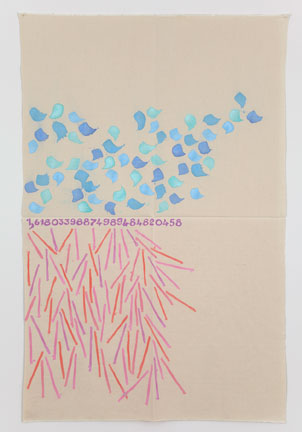

Giorgio Griffa, Camden Arts Centre, London, 26 January – 8 April

During the 1960s, as an exponent of arte povera’s lesser-known painting wing, Giorgio Griffa attenuated his medium to canvas, colour and brushstroke, laying the latter out thinly in glowing abstract battalions on exposed stretches of cloth. The result, somewhere between serialism and expressive abstraction, is at once finished – it’s on the wall – and not; something, again, in process, unfolding in concert with one’s scanning gaze. While increasingly folding in gnomic, codelike numbers, the Turinese artist, now eighty-one, has maintained his approach, and extraordinarily, as A Continuous Becoming affirms, it’s lost none of its punch or vibe of exploration. A work like 2012’s Canone Aureo 458, where a central row of digits divides an uppermost field of ultramarine and aquamarine floating commas from a lower scatter of lavender and orange pickup-sticks, is as fresh and open as Griffa’s earliest experiments in this manner: lean, sunny, mysterious, familiar, new.

Merrill Wagner, Konrad Fischer, Düsseldorf, 19 January – 10 March

Abstraction seems to be in fashion one year and out the next – last year out, probably back by now – but likely this doesn’t register for Griffa, nor for Merrill Wagner. Also in her early eighties, she began fashioning geometric abstractions during the late 1960s and has long engaged with different supports and the creative potential of their material irregularities. Lately there’s been a minirevival for her 1970s vertical-stripe works, made by painting over tape that was later removed and meticulously transferred to Plexiglas; during the 80s, she made voluminous paintings on stone, slate and steel that grew geometries around preexisting blemishes and colours, and spoke to constant natural elements: sky, desert, ocean. Recently she’s favoured salvaged steel and linen, culled inspiration from the negative spaces in scraps of cut metal and bent her composing towards, again, the natural: flowers, landscapes, deep night skies, trees. The result, melding modernist abstraction and a plainspoken love of nature, is an industrial romanticism detached from linear time in the best way.

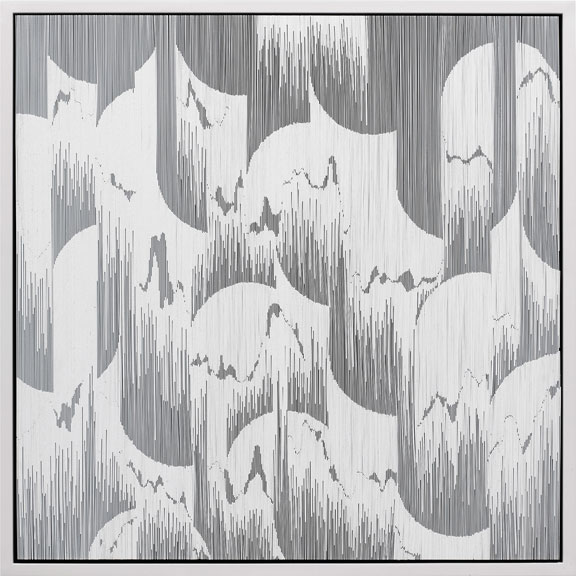

Tara Donovan, Pace, London, 24 January – 9 March

It’s hard to say if Tara Donovan’s work is abstract or not; or if that matters, really. On a macro scale the Flushing-born artist’s works tend to be biomorphic and engulfing, on the micro they’re laboriously constructed – ‘which sometimes involves an extremely tedious process’, as her Wiki unsentimentally has it – from worldly items such as toothpicks, Styrofoam cups, paper plates, tarpaper, nylon fibre, etc. Concerned, as she said recently, with ‘how the aesthetic potential of an aggregated material can be activated in ways that play with perceptual capacities’, she’s also consistently maintained a drawing practice, though her new Compositions (2017) series are only superficially part of it. Certainly they’re approximately 2D, being made of layered styrene cards, wall-mounted and framed. The results are shimmering abstractions that from a distance look like diverse graphs, close-up look like hard work and somewhere in between suggest cold mass production made consolingly charmed.

Ahmet Öğüt, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, through 18 February

In 2010, Ahmet Öğüt auctioned a self-portrait on canvas that was also designed for interaction: titled Punch This Painting, it was sold under the condition that it might be ‘punched by whoever feels like punching it every time it is exhibited’. Since then the Turkish artist has only gotten more confrontational, and less interested in the niceties of art. In 2012’s Let it be known to all persons here gathered, for the Liverpool Biennial, he had a rider on horseback, dressed as a postman, travel from Manchester to the host city, carrying a supposedly royal letter and stopping in towns along the way, not to advertise the biennale but to point up how such events don’t reach a wider public. Another side of Öğüt’s practice finds ways in which, conversely, it might yet do so, from The Silent University – a workshop-driven ‘knowledge exchange platform’ for refugees, also established in 2012 – to public sculpture. While Others Attack (2016) was a sequence of six bronze sculptures memorialising the moments when protesters during worldwide historical protests were attacked by police dogs (not shown), and another bronze shows up in No Protest Lost, his current survey in Copenhagen, commemorating hacktivist American Aaron Swartz, who committed suicide while under federal indictment in 2013, aged twenty-six.

Danh Vo, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 9 February – 9 May

A few short years ago, the title of Danh Vo’s 15-year survey at the Guggenheim, Take My Breath Away, might have scanned as light 80s nostalgia for Top Gun soundtrack fans. Fast-forward to now, though, and it chimes sombrely with #icantbreathe and activism against racial violence. All of this feels indivisible from the Vietnam-born, Berlin-based Danish artist’s consideration of power structures, colonialism, capitalism and authorship, which tends to be anchored in the twists of his biography. Capsuling Vo’s diverse practice, the show incorporates early works such as Vo Rosaco Rasmussen (2003–05), wherein the artist married and divorced friends in order to accumulate further surnames, forming a patchwork polyglot history; later pieces considering the effects of US policy in Southeast Asia, such as thank-you notes from Henry Kissinger and the chandelier that hung above the 1973 Paris Peace Accords that ended the Vietnam War; and, very probably, an element of Vo’s signature work We the People (2010–12), 30 tons of copper sheets converted into a 1:1 model of the Statue of Liberty divided into 300 discrete sections, never again to be united.

Kader Attia, The Power Plant, Toronto, 27 January – 13 May

In 1919 Abel Gance made J’Accuse, a film about the First World War in which the war-dead rise from their graves. In 1938, as the Second World War loomed on the horizon, the French director remade it, the central figure a scientist dedicated to realising a device that’d stop war forever (which, to his horror, is misused). The remake featured disfigured war veterans, playing the risen dead, as part of its aim at staving off the collective amnesia that in part permits catastrophic events to recur. And here we are again. At the Power Plant, in his show The Field of Emotions, Kader Attia channels Gance: in J’Accuse (I Accuse) (2016) he screens the later film for an array of elevated wooden busts based on the mangled men, silent witnesses to historical forgetfulness, and men who were traumatised twice: first by the war itself, then by how society reacted to their deformations. Alongside this, Attia is showing a new, untitled-at-the-time-of-writing film based on conversations with ‘various academics from the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, history and art history’ that analyses Canada’s repressed history of colonisation and slavery, the psychic wounds it has left, and how they impact the present.

Saâdane Afif , Wiels, Brussels, 1 February – 22 April

When, in 2009, Saâdane Afif won the Marcel Duchamp Prize, you couldn’t help but suspect a connection to a project he’d begun the year before, in which the French artist collects and archives every publication that uses a photo of Duchamp’s urinal. Placing another figure, or figures, in front of him is standard practice for Afif, who’s historically refused to appear in public. At Wiels, in his solo show Paroles, two core projects intertwine, each again displacing the artist: one in which, since 2004, he’s been getting people to write song lyrics inspired by his work, and a music studio where you’re invited to have a jam session, albeit under supervision and using the lyrics from Afif’s songbook (also titled Paroles). No musical skills? Develop some by listening to Black Chords (2006), an installation of automated electrical guitars playing a series of chords. Somewhere, meanwhile, Afif is sitting with his feet up, flipping through a magazine.

From the January & February 2018 issue of ArtReview