The fellowship of the West End Presbyterian Church in Richmond, Virginia, worships in a building slightly less than holy, unless you consider capitalism a clandestine religion. It used to be a catalogue showroom for Best Products, a sort of US equivalent to Argos that went bankrupt during the mid-1990s. The Presbyterians not only run the space as a church, but also as a refuge for asylum seekers and as a food bank. There used to be consumer goods here; now, thanks to the reverberations of the American Way, they’re here again. Not only that, but the building was designed – by James Wines of architecture practice SITE in a way that almost predicts this doleful trajectory, as a ‘ruin in reverse’ that was built to look weathered from the start. Such are some of the ironies that attend Scott Myles’s investigation into this specific, yet symbolic, historical continuum – which here takes the form of a series of canvases the dimensions of the artist’s studio door in Glasgow, overlaid with screen- printed ‘True-Grain’ film on which are imprinted dense confluxes of photographic material related to the Richmond church and its byzantine past.

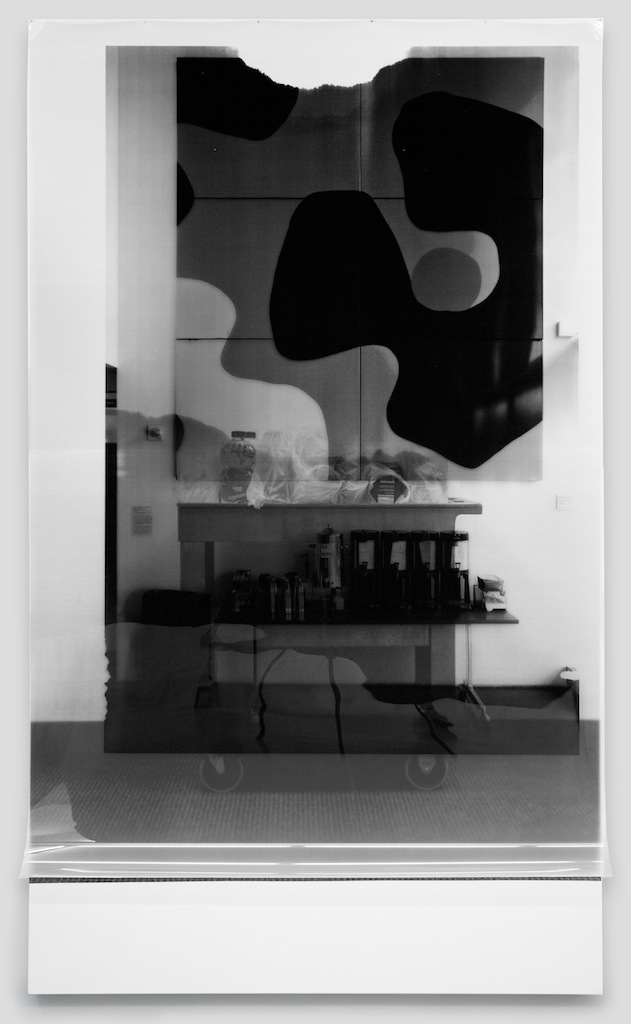

The above, though, is nevertheless just a thumbnail sketch of Myles’s research-driven process, which also involved him interviewing Wines – a moment memorialised in one of the tenebrous, wall-based works, in which we can see Myles’s hand holding the keys to the architect’s office – and, elsewhere, discovering how the Best owners were major art collectors and had sought to offer Wines, himself a former artist, Best products in return for a piece of his art. Art and commercial products, both subject to rises and falls in their fortunes, entangle strongly here. Their meshing, indeed, is suggested in the very materiality of Myles’s works, which are so dense in their multiple exposures that one can’t always see what’s going on: a fragment of architecture here, some shelves containing food-bank products there, an abstract painting that might have belonged to the Best owners, all coalescing into merging forms. We see the past, and present, through a print darkly.

There are two ways into this. You either go down the footnote-rich rabbit hole of Myles’s investigations, admiring his ability to ferret out mordant connections, or you take on the poetics of his aesthetic, which signals the complexity and unpredictability of the historical process and, particularly, the instabilities and switch-backs that attend capitalism. It’s notable that the work leads back, quite literally, to Myles’s studio door, ie, to art, and that his countermanding interest is in gift exchange. In a recent project titled Potlatch (2014), not on display, he replaced the gift-wrapping paper for Galeries Lafayette Maison with Bible paper imprinted with images of Guy Debord’s shuttered house: the inactivity of the great critic of consumerism was here reversed into mobility and circulation emanating from a centre of consumption, and pinned to the notion of the gift. One senses that Myles, when not engaged in attentive archive delving, has closely read Lewis Hyde’s classic 1983 study of art as pay-it-forward contribution, The Gift. One takeaway from Spiral Bound and its food-bank endpoint might be that if capitalism continues to unravel and spread ruination, we are bound to spiral back towards older forms of exchange and generosity – ones in which art, while currently conflated with commerce, might still be exemplary.

21 November – 19 December 2015, Meyer Riegger, Berlin

This article was first published in the January & February 2016 issue of ArtReview.