Siributr’s textile works emerge from times of conflict and violence, setting horror and yearning in fabric

Three large tapestries open the exhibition. Each hanging on a horizontal pole like torn, despondent flags, these are made from joined uniforms worn by former Thai public service workers, we’re informed by the wall text. In one (Airborne [Klongtoey], 2022), bright orange vests worn by motorcycle taxi riders are reshaped into facemasks and stitched together, while uniforms of street sweepers are embellished with coin-shaped amulets in another (LD20, 2023). Figurines of bodhisattvas, ascetic monks, amulet lizards and other such touristic spiritual trinkets dangle from each, like loose threads hanging from a piece of worn-out cloth. Thai artist Jakkai Siributr bought these uniforms from workers who had lost their jobs during the COVID pandemic, during which time Thailand’s bustling tourism industry virtually came to a stop. (Prior to the pandemic, tourism made up a fifth of the country’s GDP) These brightly coloured jackets, designed for visibility, were rendered as invisible as the workers themselves.

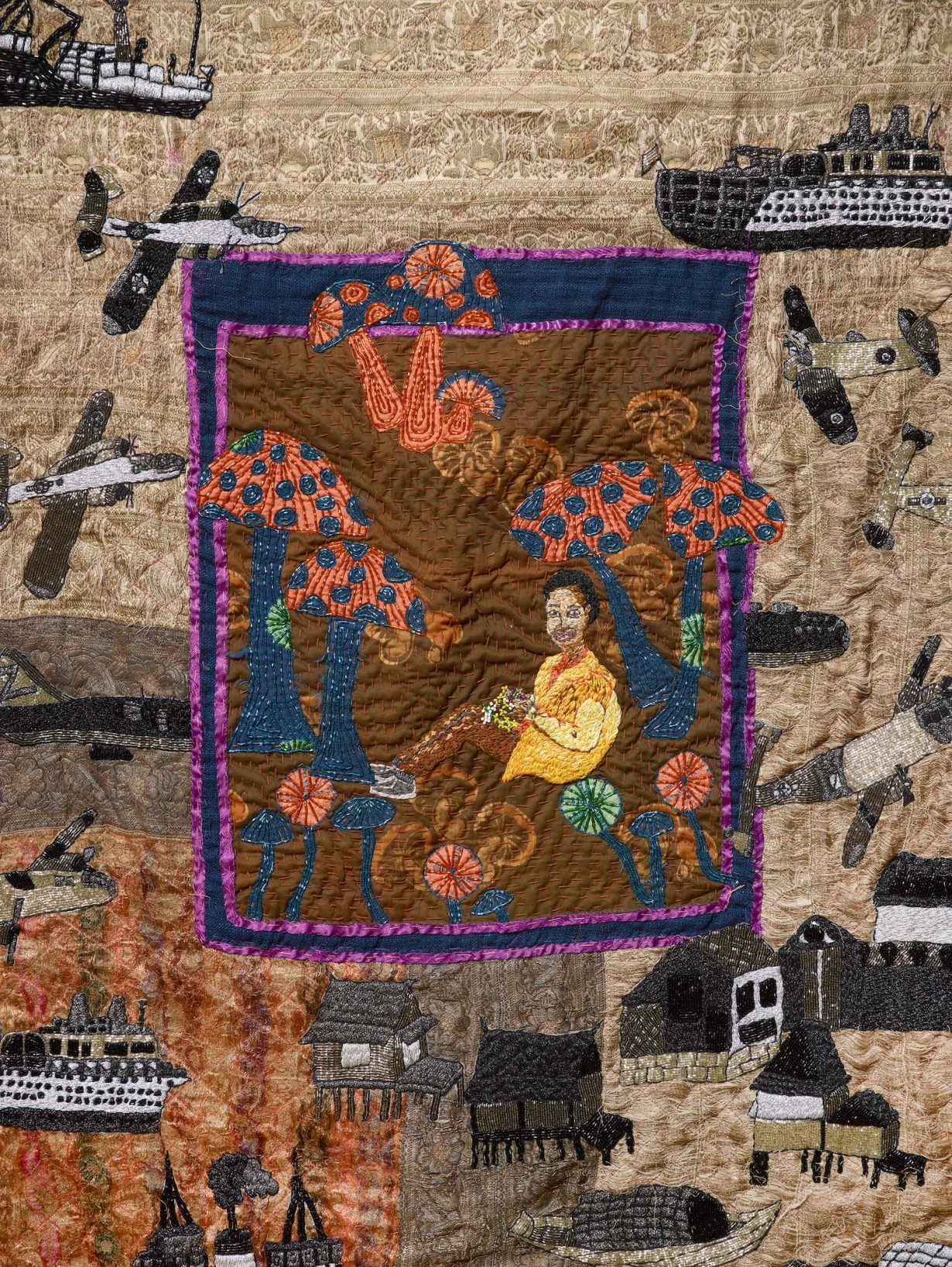

Siributr’s textile works often emerge from times of conflict and violence. His exhibition at the Whitworth, his first institutional solo in the UK, consists of a single room of works as well as a large installation, There’s no Place (2019–), in a corridor adjacent to the institution’s own fabric collection. The latest iteration of this ongoing project, which he initiated while working with Shan refugees at the Koung Jor Camp in northwestern Thailand, close to the border it shares with Myanmar, comprises rectangular pieces of cloth hanging from the ceiling, filled with words and faces. Embroidered by the young residents of the camp, the naive imagery ranges from Shan alphabets to family portraits, evoking memories of home as well as the yearning to belong.

Back in the gallery room, displayed next to the tapestries, Siributr’s Changing Room (2017) points to the violent reality of Thailand’s deep south, where clashes between the region’s Malay-Muslim separatists and the Thai military are frequent. Arranged around a full-length mirror, Changing Room consists of embroidered military uniforms and white songkok caps worn by Muslim men. The work invites members of the audience to try them on, but once you do, you discover that the caps’ inner linings are made of military fabric, on which horrific images of beheaded orange-robed monks or soldiers with machine guns are embroidered in a childlike style. Putting one on provokes the uncomfortable feeling of being in contact with these violent realities – a gesture that forces you to bear them in mind, and let the horror settle in.

The forms of absent bodies are hauntingly present in the gallery’s intimately sized room. In Broadlands (2023), made with the clothes of Siributr’s late mother, shawls and blouses in various shades of pink and beige are suspended midair, twisted and sewn together as if caught in a restless and drawn-out embrace. Jewels and pearl necklaces hang down from the fabrics like tears, mirroring the hanging figurines cascading from the service-uniform tapestries. Surrounded by the more politically informed works, Broadlands feels like an altar and evokes a sense of movement, of his mother’s figure as well as his own sewing, grieving hands. Behind it, a series of thangka-like fabric collages picture his female family members, overlaid with appliqués of drones and planes. Matrilineal (2023) depicts his family amidst the same visual vocabularies that constitute scenes of aggression in his other works. Taken together, the works give us a sense that the political and the personal are tragically intertwined. To survive loss and bereavement – and to live with trauma – is a struggle that implicates everyone.

Jakkai Siributr, There’s no Place, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 15 November – 16 March