As the Warburg Institute reopens in London, why does its founder’s star burn brighter than ever before?

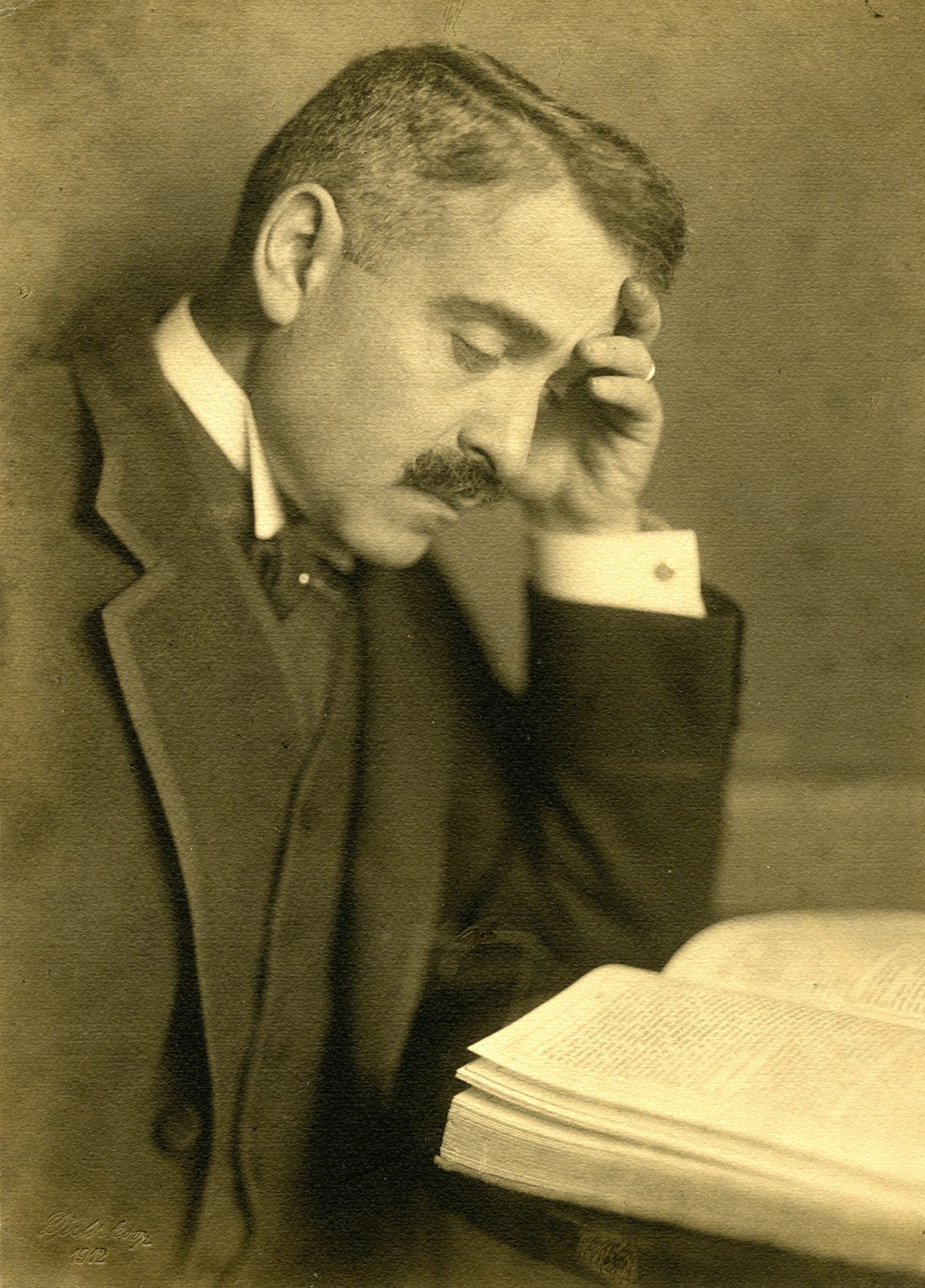

Remarkably, and unlike his contemporaries Alois Riegl and Heinrich Wölfflin, who are often credited with ‘founding’ the discipline of art history in its current form but have remained mostly of interest only to art historians, fellow art-historian Aby Warburg has become a key reference point for various contemporary artists, critics and curators. Perhaps even more so than during his lifetime. Not only is it remarkable that Warburg, who died nearly a hundred years ago, is now better known than his contemporaries, but also that his writings – which are often somewhat fragmented and incomplete, partly due to his struggles with mental health – continue to resonate. Major exhibitions such as Atlas. How to Carry the World on One’s Back? at Madrid’s Reina Sofía in 2011, curated by Georges Didi-Huberman, read artists such as Christian Boltanski, Zoe Leonard and Walid Raad through Warburg’s work and his Mnemosyne Atlas, his large collection of photographic reproductions of artefacts arranged montage-fashion on panels. The Mnemosyne Atlas was itself the subject of an exhibition at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin in 2020 and served as the foundation for the display at the Chinese Pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale. And if there has been a revival of magic and occultism in contemporary art – Alice Bucknell’s online platform ‘New Mystics’ being emblematic – then Warburg’s approach to art history, which acknowledged the function of astrology in visual culture as a viable intellectual means for apprehending the world, would seem a vital resource.

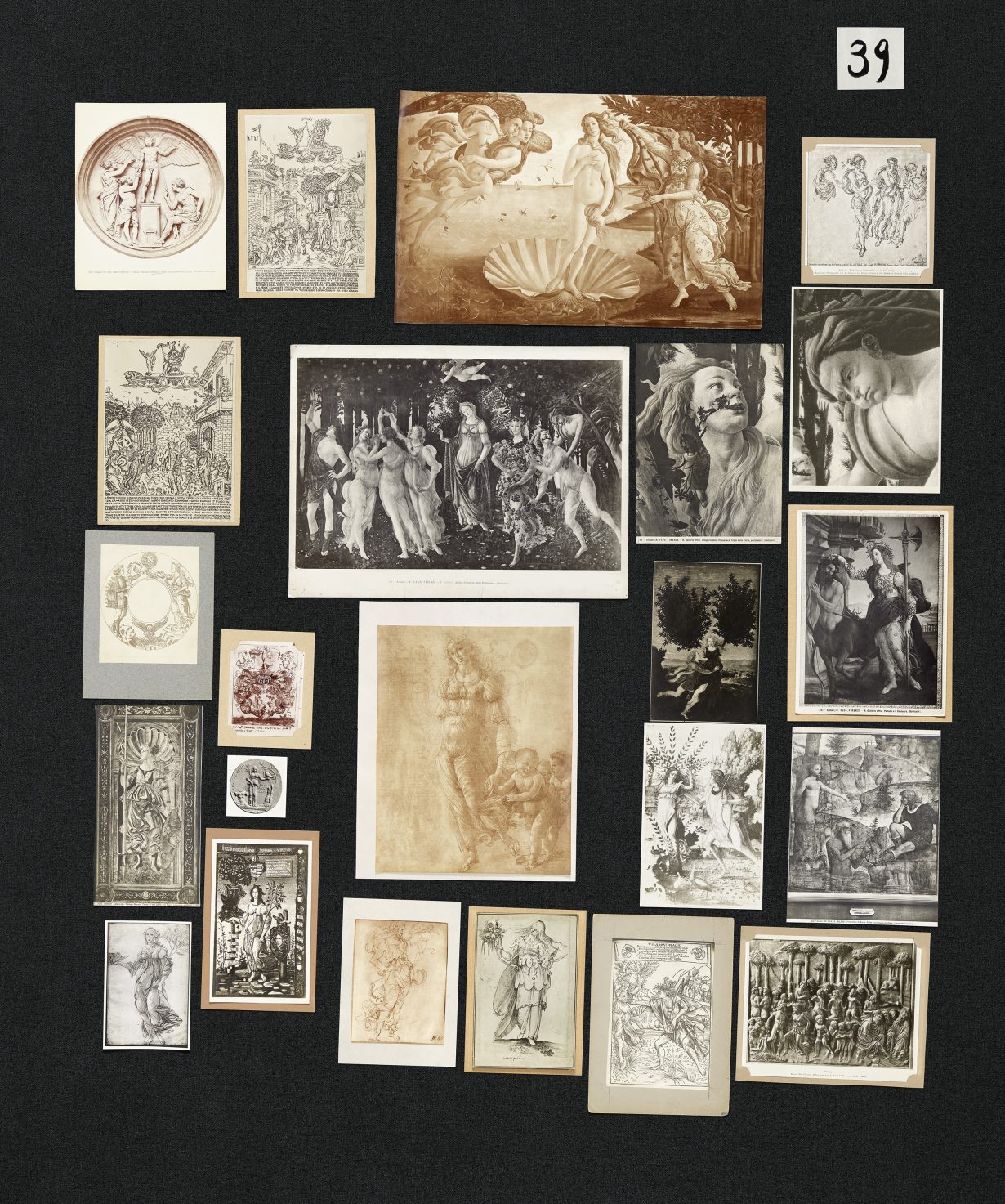

Warburg’s importance to contemporary art mostly relates to his Mnemosyne Atlas, properly begun, according to the Warburg Institute, in 1927 and unfinished at the time of his death in 1929. Consisting of some 1,000 photographic reproductions of artworks and visual artefacts provisionally arranged by Warburg on numbered panels, the Mnemosyne Atlas sought to recover and demonstrate through visual means the survival of pagan antiquity in the Renaissance. Each panel was photographed on ‘completion’, with the aim of publishing a book that documented all the panels in sequence. In October 1929 he had arranged a third iteration of the work, amounting to 63 panels, though Warburg’s numbering system suggests that another 11 were still to be added. Unfinished, and perhaps unfinishable, the Mnemosyne Atlas reflected the rise of the photobook in Weimar Germany and has been understood in terms of 1920s avant-garde montage strategies. Later artworks, such as Gerhard Richter’s Atlas and Hanne Darboven’s Cultural History 1880–1983, resemble Warburg’s work, even if made without awareness of the Mnemosyne Atlas. Its influence upon contemporary art might temptingly give the impression that Warburg’s oeuvre is more looked at than read, though Warburg’s thought troubles that very dualism. Adopting a phrase from Walter Benjamin – who can, at times, strike one as a kindred spirit – Didi-Huberman proposes ‘reading that which was never written’ as a leitmotif of Warburg’s enterprise.

Aby Warburg, Mnemosyne Atlas, 1929 (last version), Panel 39 (reconstruction by Roberto Ohrt and Axel Heil, 2020). Photo: Tobias Wootton. Courtesy Warburg Institute/Fluid, London

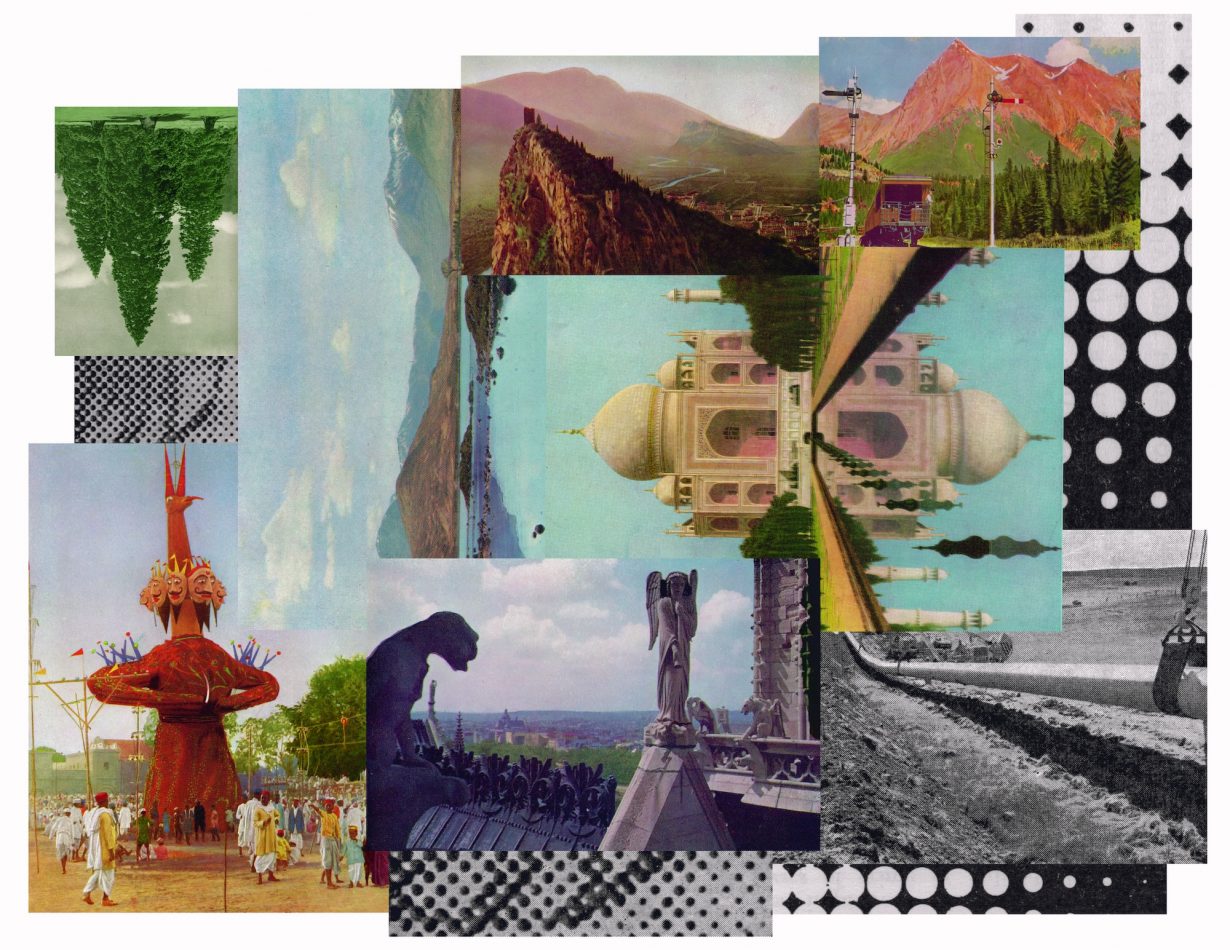

Visual literacy, dependent on perceiving images assembled with other images, reveals temporal dynamism. But this dynamism isn’t restricted to the Renaissance; it’s a feature of our present, too. Mick Finch’s Book of Knowledge project, initiated in 2014, appropriates Warburg’s montage procedures by juxtaposing readymade photographs taken from a late-1950s edition of a popular encyclopaedia; rearranged and put into new relationships, the images become less tokens of their time than prefigurations of our present – almost as if they’re tarot cards becoming meaningful via interpretation. That constellating of images generates meaning (as if no image alone can perform that function) and parallels how machine learning requires feeding multiple images deposited according to categories in order to learn how to read, sort and then produce images. The Mnemosyne Atlas, perhaps, has become a primer in how to navigate an image world, although whether that lesson is extendable to the burgeoning panoply of AI-generated images is another question. But insofar as those images are products of human desires and biases, then a Warburgian art theory might well provide a means for comprehending the ghosts in the machine.

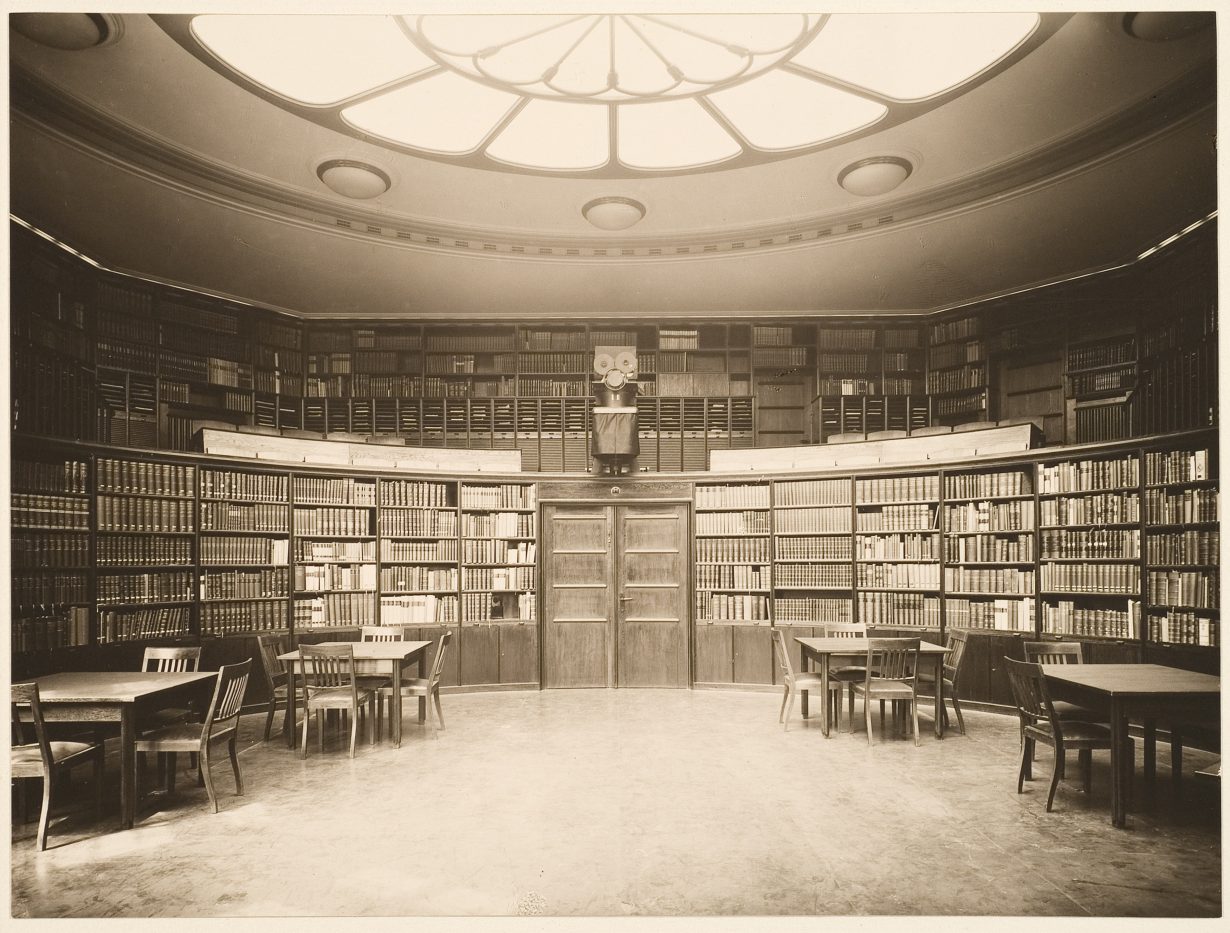

Warburg, the scion of a wealthy Jewish banking family in Hamburg, elected to train in art history rather than head the bank. As a result of a childhood deal made with his younger brother, Max, the latter would inherit the bank on condition that he purchase any book the former desired. Aby thus amassed a huge library (the foundation for what later became the Warburg Institute) that reflected his conviction that the Renaissance was not simply the birth of Christian humanism, supposedly lifting European culture out of medieval darkness into a new realm of achievement, but also the reappearance of a ‘daemonic’ worldview that was a ‘survival’ – in German, a nachleben – from pagan antiquity. For example, Warburg’s 1912 lecture on murals in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara affixed upon what he interpreted as astrological symbols taken from Ancient Greece. Art history, paraphrasing Warburg, was really a set of ghost stories for adults that disrupted linear history and showed how the past refuses to pass. Warburg’s library, organised according to his ‘law of the good neighbour’ – in which the books were not distributed on the basis of standard classification systems but through a subjective logic in which a volume on magic can sit alongside a study of Lutheran theology, thereby casting light upon each other – was a creative instrument for disclosing this hidden dialectic between Apollo and Dionysus (Warburg was a reader of Friedrich Nietzsche, in whose first book, The Birth of Tragedy, 1872, this dialectic is explored) and their untimely continuation in later cultural formations.

Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg, Reading Room, 1926. Courtesy Warburg Institute

Fritz Saxl, an art historian and librarian who had been close to Warburg, was instrumental in converting the library into a research institute and relocating it to London in 1933, four years after its founder’s death, to safeguard it from the Nazis. A decade later, it became part of the University of London. But despite the prevalence of the institute, especially in the disciplines of art and cultural history, Warburg himself has largely had a subterranean presence in those areas, partly due to the influence of art historians Erwin Panofsky in the U S A and E. H. Gombrich in England, although they were at the same time important conduits in determining Warburg’s reception in academic circles. Both Panofsky and Gombrich were Jewish émigrés fleeing Nazism. Panofsky had been directly connected to Warburg, researching in his library at Hamburg and even completing Warburg’s unfinished project on Albrecht Dürer’s mysterious print Melencolia I (1514), which depicts an array of esoteric items clustered around an angel. Gombrich left Austria in 1936, becoming, in 1959, the fourth director of the Warburg Institute and writing, in 1970, a biography of Warburg. According to both, Warburg’s research into the Renaissance demonstrated a transition from the Dionysian (the irrational, the magical) towards the Apollonian (the rational, humanist). Whatever tension existed between the Dionysian and Apollonian in Renaissance culture testified to this transition being underway. Panofsky’s essay ‘Albrecht Dürer and Classical Antiquity’ (1922) and Gombrich’s biography problematically advanced an interpretation of Warburg in which he acted as the defender of Apollonian values.

To some extent, how Panofsky and Gombrich summarised Warburg’s distinct art-historical approach held sway, especially in Anglo-American art history circles, from the mid-twentieth century until the 1990s. The complexity through which Warburg approached nonlinear time within Renaissance artworks was largely unrecognised. It was also as if the existence of the Warburg Institute was enough, and Warburg himself, or his ideas, were strictly secondary. Gombrich’s directorship, though, coincided with groundbreaking publications by scholars at the institute, Frances Yates and D. P. Walker; the former’s investigations into the reception of the Hermetic texts and the troubled career of Giordano Bruno in books such as The Art of Memory (1966), with their self-confessed speculative qualities and open-endedness, are closer to the spirit of the research methods used by Warburg than the image of the man posited by Gombrich. Like Warburg, they construed hermetic thought and occultism as compelling philosophical systems capable of illuminating facets of the Renaissance, thereby also complicating the apprehension of that period afforded by mainstream scholarship. And also like Warburg, they acknowledged the tentativeness of their research, encouraging others to continue exploring the paths they opened.

Portrait of Aby Warburg (1912). Courtesy Warburg Institute

Interest in Warburg, a fascination even, has deepened in the last few decades, allowing the complexities of his thought to become visible. Translations of continental philosophy and the rise of postmodernism during the 1980s in many ways encouraged a framework through which Warburg’s art history can be viewed anew. Art theorist Margaret Iversen was a pioneer here; her 1993 essay ‘Retrieving Warburg’s Tradition’ critiqued the timid domestication of Warburg by Gombrich and Panofsky and cogently asserted that his position could be aligned with postmodernist and feminist perspectives. Similarly, art historians such as Matthew Rampley and Georges Didi-Huberman have succeeded in recovering Warburg’s conceptual approaches, especially his belief that time was not a straight line or a progressive march towards a better future but more like a constellation in which past and present exist simultaneously and haunt one another. As such, Warburg’s writings provide tools for understanding the complex temporalities examined by artists such as Doug Aitken and Tacita Dean, among others, while it impacts upon how the art historian comprehends the artwork in its ‘present’, since the notion of the present, for Warburg, is the survival of the past. Artworks, then, are perhaps defined by Warburg as being perpetually both in and out of context, and ‘anachronism’ is no longer a condemnation but a condition of art.

Memory and Migration: The Warburg Institute 1926–2024 is on view at the Warburg Institute, London, 1 October – 20 December

Matthew Bowman is an art critic and art historian based in Colchester