‘Dostoevsky, I thought, had maybe changed him and, to a person as dissatisfied with their own personality as I am, might rewrite me’

On a sultry May evening in the vanished world of 2008, I was sat in the garden of a collector’s house in Bergamo, Italy, after a private view at the city’s art museum of an exhibition by Kris Martin. As dusk fell and the far end of the lawn lit up magically with fireflies, the Belgian artist told me about a work he’d made three years earlier in which he’d hand-copied Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1874 novel, The Idiot. Actually, he didn’t specify at the time that it was a work (as opposed to an ascetic pastime), but there were several sculptural works in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea (GAMeC) show related to the same literary masterpiece. This project, however, even in hearsay or perhaps because of that, struck me more deeply. It made me wonder what kind of person Martin was. Because he’d done the copying, he said – a daily act for months, one that sounded monastic, penitent – as an act of overt identification with the title character, the holy fool Prince Myshkin, and indeed had replaced every iteration of Myshkin’s name with ‘Martin’. And maybe it had worked, because the artist, at least on that one encounter, seemed an uncommonly kind, soft-spoken, courteous type, his character later thrown into relief when I guzzled too much chilled Trebbiano and my tongue sharpened into random bitchiness. “You were being so nice,” said Martin, dismayed.

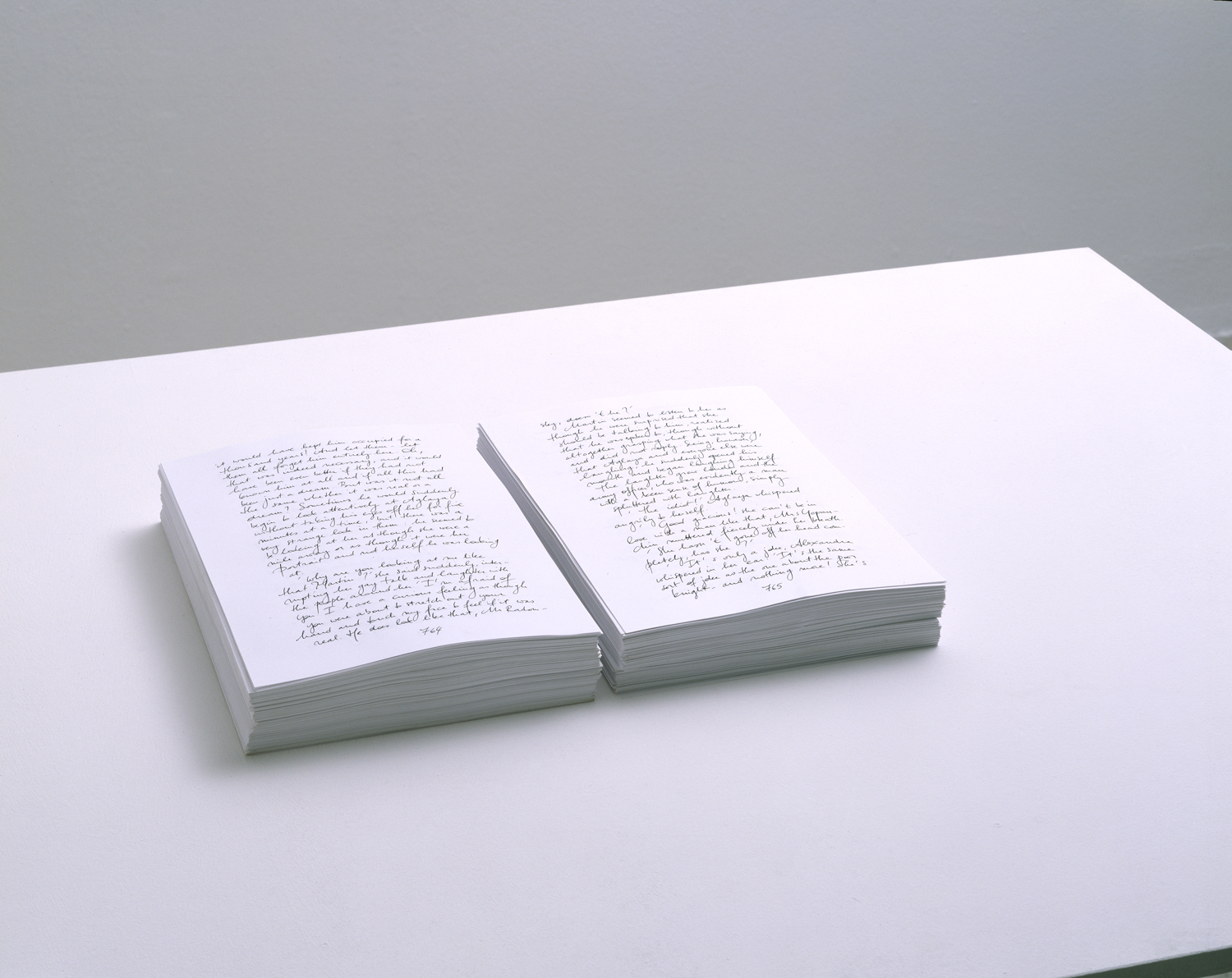

The next day I got up, hungover, and, reading in a guidebook that Le Corbusier had described a particular square in Bergamo’s old town as the most beautiful in Europe, walked to the Piazza Vecchia. It was covered in scaffolding; I felt toxic, ousted from goodness. When I got home I swiftly bought a copy of The Idiot. I thought about copying it out – I could write ‘Martin’ too, I suppose – but settled for just reading. I loved it, and had some kind of afterglow; I became, for a while, gentler, kinder, if nowhere near saintly. The effect was a mixture of Myshkin and the memory of how Martin had conducted himself that evening. And how I’d conducted myself, too. By a weird process of displacement and mirror neurons firing, I’d been inspired not by an artwork but a verbal description of one allied to a notion of its maker’s mien, which in this case is maybe as much as you need, because even when you see Martin’s Idiot (2005) – which is currently on view in his show at S.M.A.K. in Ghent – you can’t read it. You can’t even know, aside from the description, that there is writing on all the 1,494 A4 pages stacked inside a vitrine. But Dostoevsky, I thought, had maybe changed him and, to a person as dissatisfied with their own personality as I am, might rewrite me: a sucker’s game that, historically, I’ve somehow never completely tired of.

Now, I don’t really know Kris Martin. From others who’ve met him I’ve heard conflicting reports, and arguably you don’t copy out the whole of The Idiot because you already think you’re like Myshkin; you might more likely make the commitment if you feel you’re very much not, maybe if you’re seeking some stabilising, positive, ritualistic force in your life. (Martin is nevertheless, I should note, the only artist I’ve ever met just once who, months later, phoned out of the blue to see how I and my family were getting along. After that, we somehow lost touch.) I’ve never seen his Idiot in real life; and yet it affected me as an idea, filtered through circumstance, more deeply than many works I have seen. It’s an artwork with a performative level built into it, and there is nothing to stop you, the viewer, aspiring to that same level. Its maker, I would guess, didn’t intend his artwork or his behaviour on one evening in which he had every reason to be in a good mood to be a vehicle for a viewer’s soul-searching about their character flaws, but art ends where it ends, and I can laugh about it now, sort of.

What was at work here, perhaps, was what Harold Bloom called ‘creative misprision’: misinterpretation that becomes productive. And then it goes away, the transfiguring and vitalising effect; and you need something else, or you get tired of bending your personality into a caricature. I said reading The Idiot via Idiot changed me for a while, but it’s in the nature of afterglows to fade. One day you find the thing that inflected you doesn’t work anymore. To the extent that art is functional, one function of it might be to irradiate and intoxicate the viewer – I see the world differently after visiting the work of certain photographers, becoming attuned to the potential for beauty and grace in the everyday – but, to mix metaphors, you have to keep going back to the well, failing better.

When I do studio visits, I often ask artists if they feel they learn things from looking at their own work. Many of them say yes, which illuminates, I think, an underrecognised aspect of artmaking: that it can be physiologically transformative for the artist, too. Hiroshi Sugimoto once told me that every time he looked at a seascape he was “powering up [his] eye”, that the act of looking improved his vision. There are numerous examples of artists who, at some point, have gone tabula rasa – emptied their studio and built up again from nothing. In his 1982 book about Robert Irwin, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, Lawrence Weschler describes how Irwin, previously an abstract expressionist, stripped his art back to a single line on canvas, which he would stare at and occasionally delete and reposition, for hours and days. Tom Friedman once cleared his workspace, painted everything white and stayed in there doing nothing until, finally, he poured a pool of honey on the floor. He then started a jigsaw puzzle, which he spaced out into a grid; from there, having reset himself inwardly, he could move on, reboot his practice. Agnes Martin meditated before painting, which presumably led to a lot of meditation and the somatic benefits of same.

So probably I should have asked Kris Martin if writing Idiot changed him, though I think I didn’t want to hear if it didn’t; that there was no mechanical bridge, no shortcut, from one mode of selfhood to another, calmer one. But selfood is also flux, a fact that we don’t always like to face. In one study, people were asked if they thought they’d changed a lot in the past, and they mostly said yes, but when asked if they thought they would change a lot in the future, they mostly said no. We think we’ve arrived at our final self, just as we think human evolution has ended. In 2010 Martin made a work titled I Am Not an Idiot, a row of found pebbles whose markings looked enough like letters to spell out the title. Maybe Idiot was a stabilising act, because another thing artists often have is a process that they can do almost mindlessly that keeps them ticking over in the studio. Maybe it was all of this or none of it. But this text is about what, and how much, it might be for someone else, once it enters the vicissitudes of reception. Art shouldn’t be self-help, but among the things it can be is a temporary course correction – even if, ironically, it deflects attention away from itself and onto a deeply humane work of nineteenth-century literature – or one of a lifetime of them. Which reminds me, I need to read The Idiot again. It’s been years, and I can’t remember a word of it.