The enigmatic graphic artist continues to open new doors in experimental comics and has sparked a legion of imitators

Broken vision quests. That’s how I’ve come to understand the comics art of American cartoonist CF – nom de plume of polymathic graphical innovator Christopher Forgues – whose impish characters and non-Euclidean panels have been unsettling expectations of what the medium might do since the early 2000s. Derailing the phallic linearities and big treasure money shots of the sword and sorcery tale, these short, often fragmentary vignettes have developed their own skewed sensualities, absurd physics, and seductive critiques of power (often choreographed through comedic S&M theatrics) over the last quarter century. As a result, they’ve not only furrowed out their own hybrid science fantasy genre, but carved a deeply-wrought fissure of individual comics practice that lies far beyond and beneath the polished slop worlds we’ve come to expect from industry titans Marvel or DC. It might seem nonsensical to talk about an ‘underground’ culture in an age of networked instantaneity, but these fissures run deep, and they harbour a multifaceted comics sensibility as wondrous and beguiling as a crystalline seam.

In the opening strip of Distant Ruptures, a new anthology of CF’s short works originally produced between 2000 and 2010, a doughy-faced traveller finds himself seeking rest at an outpost after a long trek through mysterious woodlands. The outpost’s proprietor, a cheery feather-capped gent, offers the fulsome hospitality characteristic of a fantasy tavern landlord. Things quickly go arsy-turvy however as, over a series of agonising but deeply funny panels, we realise that the traveller is only sleeping so well in this new place of respite because he’s been intentionally poisoned by his host. He wakes repeatedly, straining to see the molten face of his captor through bleary eyes, only to be told each time that he’s been asleep for thousands of days.

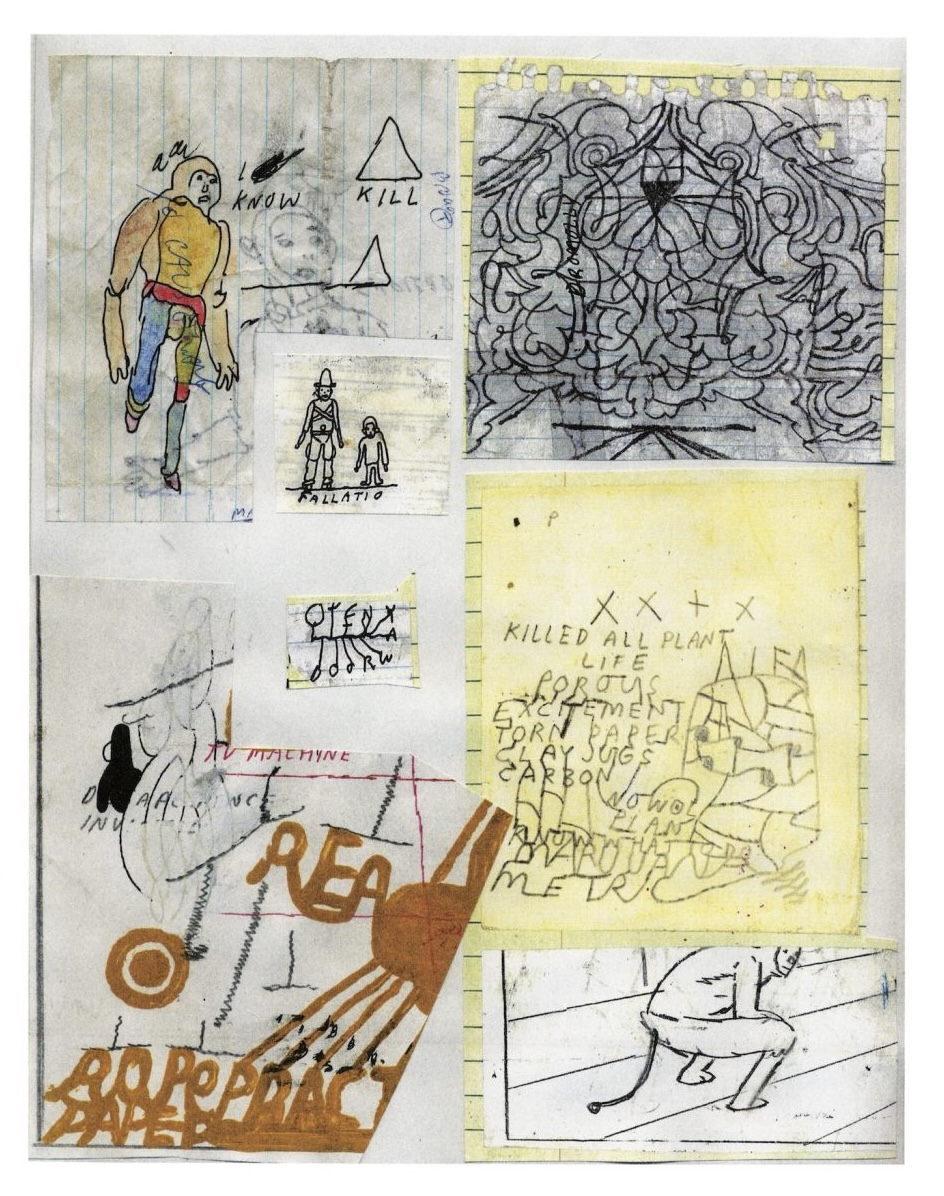

These disconnected bouts of lysergic strangeness are reminiscent of how it felt to encounter CF’s consciousness corrupting works in the period they were produced. Appearing as clusters of ephemera, photocopied chapbooks or carefully screen-printed zines, and often distributed in small curious editions to be foraged at noise gigs, sourced from certain comic bookstores, or ordered directly through the artist’s own industrious mail art schemes, these works were mysteriously authored and infrequently chanced upon. Finding them felt like a minor victory, their splinters of disconnected narrative presenting a subtle riposte to the supposed majesty and cohesion of the graphic novel that was quickly becoming the toast of broadsheet culture sections.

A key member of the now mythic community gathered at Fort Thunder, in Providence, Rhode Island – a warehouse collective that from 1995 to 2001 played home to DIY noise and renegade graphics outfits Lightning Bolt and Forcefield, and that provided a testing ground for the poisoned psychedelia of artists Brian Chippendale and Matt Brinkman – CF’s early works emerged at the turn of the millennium via collaborative imprints like Paper Radio, co-assembled with artist collective Paper Rad’s Ben Jones. Unlike Jone’s own brilliantly nihilistic THC-soaked riffs on children’s TV staples Gumby and the Muppet Babies, CF’s work presented short vignettes that smeared the apparently quotidian into the deeply epiphanic, channelling both the spirit and energy of a particular strain of independent comics, from Gary Panter’s quivering punk odyssey Cola Madness, John Porcellino’s zen confessional King-Cat, and Jenny Zervakis’ emotionally resonant Strange Growths, to the experimental postwar manga of Ebisu Yoshikazu or Yoshiharu Tsuge, into something deeply studied and yet jarringly new.

Through the mid-to-late 2000s, his strips began to punctuate era-defining alternative comics anthologies, such as indie stalwart illustrator and editor Sammy Harkham’s Kramer’s Ergot (2000-2019), Jonas Delaborde and Hendrik Hegray’s warped graphics directory Nazi Knife (2006-), and even infiltrate the pages of a Harkham-edited special edition of The Simpsons’ Comics Treehouse Of Horror (2009) with a bonkers bootleg, ‘The Slipsons’; and yet there always remained a sense of mystery to their provenance. This was due in large part to the artist’s enigmatic initials, which, when twinned with his own reluctance to embrace an online identity, often baffled search engines. When comics historian Dan Nadel opted to publish a series of interconnected strips in the three-book series Powr Mstrs (2007-2010) through his pioneering Picture Box Inc. imprint, the vagueness persisted. Where did these comics come from? Who was making them? When the hell would the next one appear? Would we ever reach the end of the story?

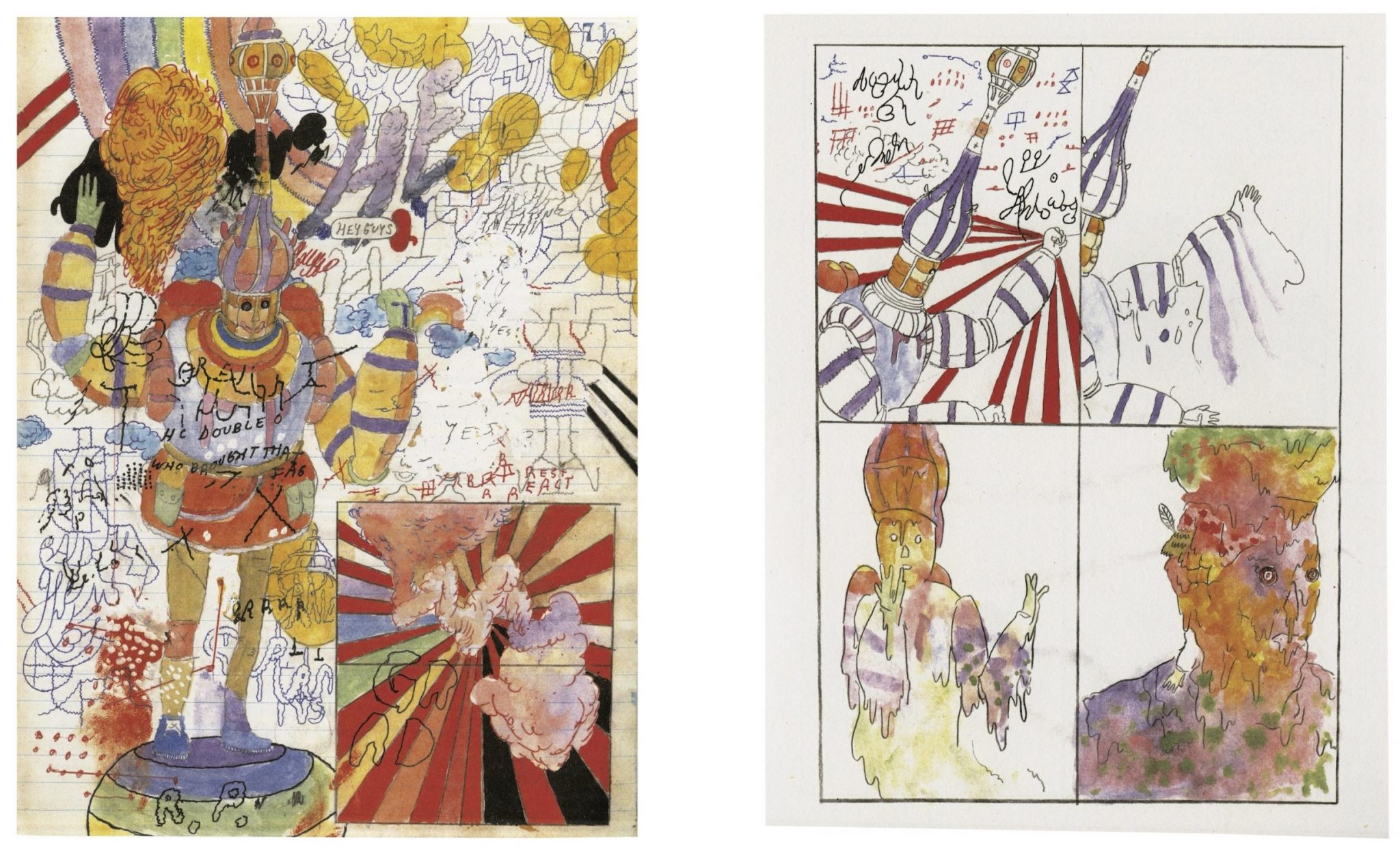

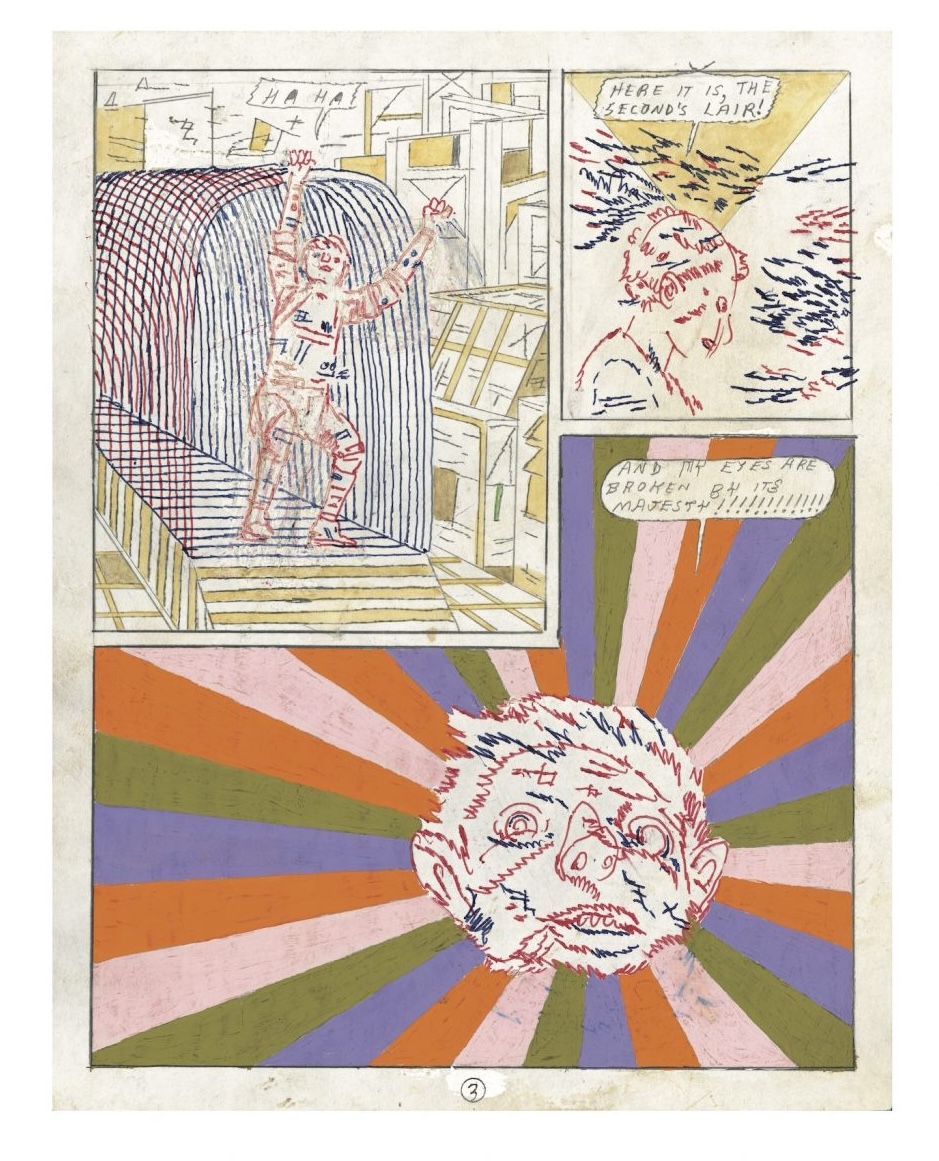

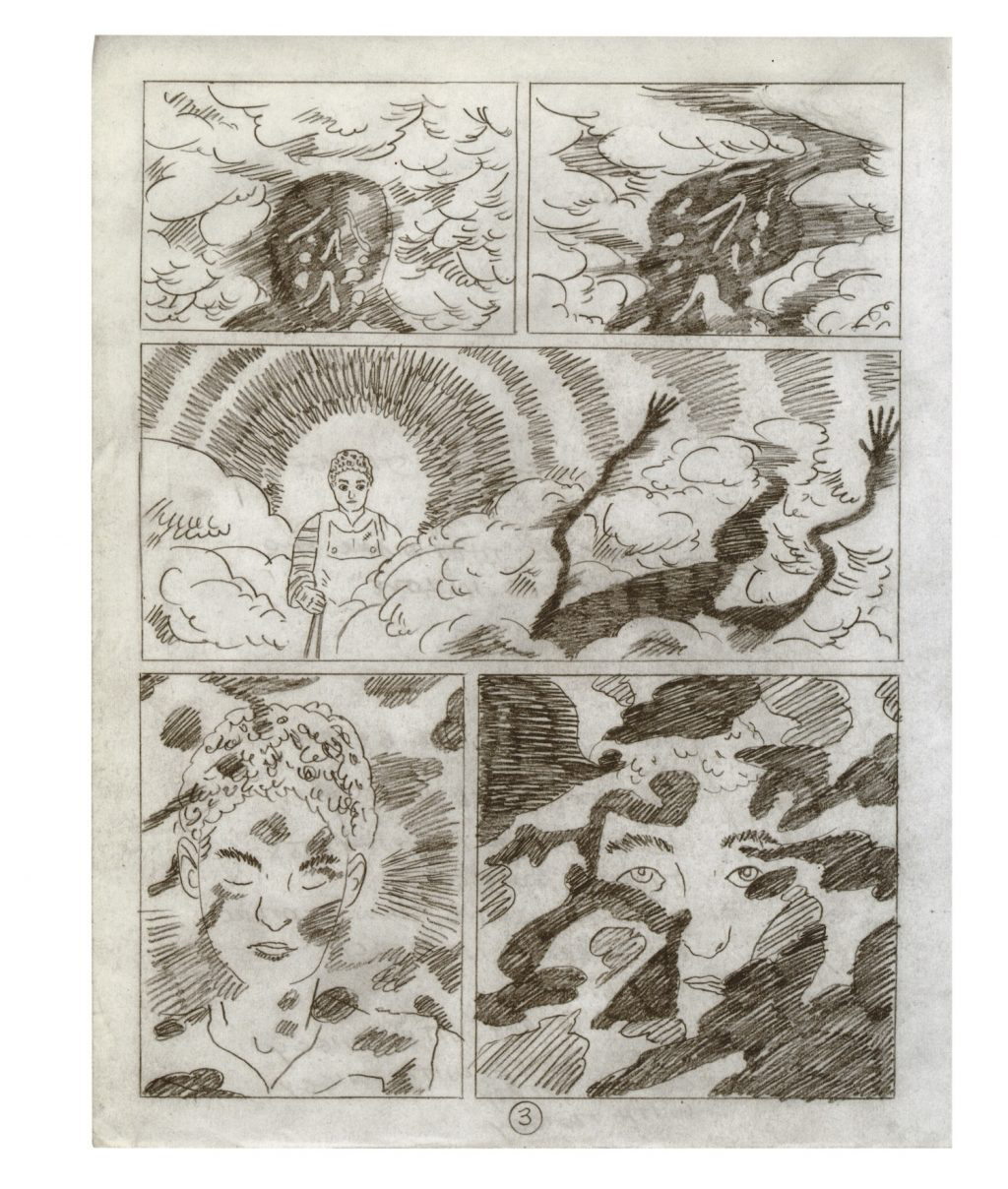

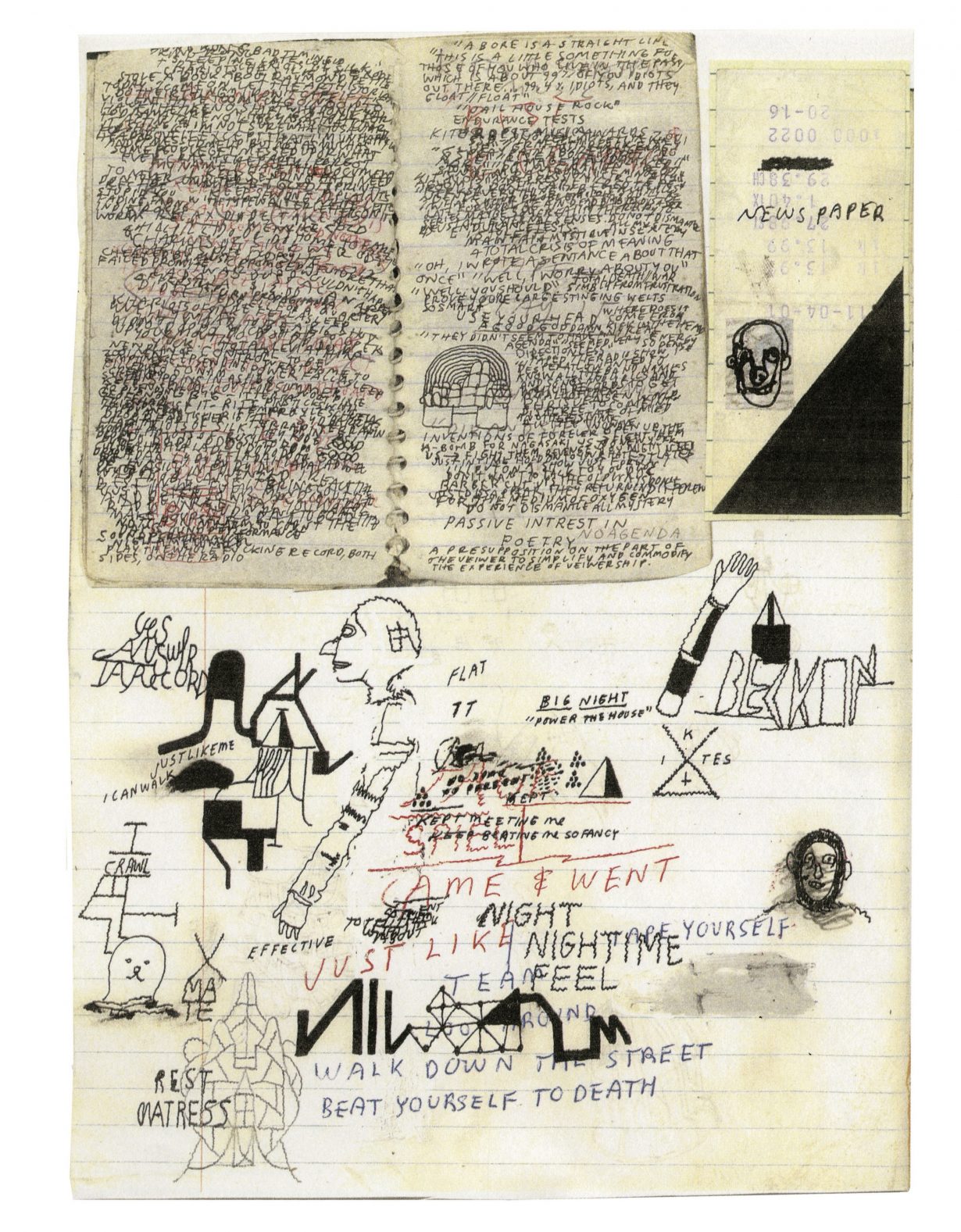

But while the author may have remained elusive, the comics, with their own tones of fey weirdness, were instantly recognisable. The deftness of their draughtsmanship, the craft of their line work (a kind of schizoid Mœbius-in-progress pencil craft that could either cut its lines plainly or feather itself into noisy obliteration), or in the notational rubble of jottings and authorial asides that coalesced around their fragmented panels as scrawled communiqués or blasted Letraset – the marginalia where the artist would announce himself as a ‘hard worker, slime freak’, call out others for ‘biting’ his style, or give brief allusions to breadth and depth of his own reading. This style was really honed throughout Powr Mstrs, which contorted his panels into resonant new expressions of liquid insanity or reflective stillness while relaying the semi-sensical story of ‘Known New China’. Whether bound in books, or occupying ephemera, CF’s works always appeared to be reinventing their own formal languages from episode to episode, often collapsing different approaches to materials or printing techniques directly into the structure of the comics themselves.

In doing so, his work would also reinvent a particular kind of storytelling, appearing to untangle the pulp heroism of Fritz Lieber, Jack Vance or Michael Moorcock with the digressive illogic of the stoner. There are rarely any villains here; just elfin avatars subject to the formal free-fall of comics experimentation. And with hindsight, it’s a little easier to see what a subversive contrast their fragmentation of fantasy tropes posed to the cinematic fever dream of Peter Jackson’s Lord of The Rings trilogy (2001-2003) as it unfolded its own cinematic mythos against the televised odyssey of an American War on Terror keen on pursuing its own vaguely defined nemesis in the East.

Edited by Harkham, and published in a prestige hardback binding by New York Review of Comics, Distant Ruptures does an incredible job of gathering together and showcasing CF’s work through a period of intense experimentation. If you were lucky enough to catch some of these works the first time round, either as anthology entries or limited editions, you’ll be aware of how risky such an exercise might be. Paper stock, irregular formats and unique paginated rhythms were always key aspects of the CF reading experience. It’s what the Mexican philosopher of artists’ books Ulises Carrión was gesturing toward when he described a book constituting its own unique ‘space-time sequence’. And CF himself has always been keen to stress the importance of time in his works, regularly imploring us in his marginalia to ‘read at a medium to slow pace please’, or not to ‘read too fast’. Distant Ruptures might flatten the varied times of these works into the measured pace of a retrospective survey, but they’re no less weird or unusual for it, as narrative comics constantly bristle against page upon page of crazed cursive, show flyers and freeform renditions of what has been called ‘psychedoolia’.

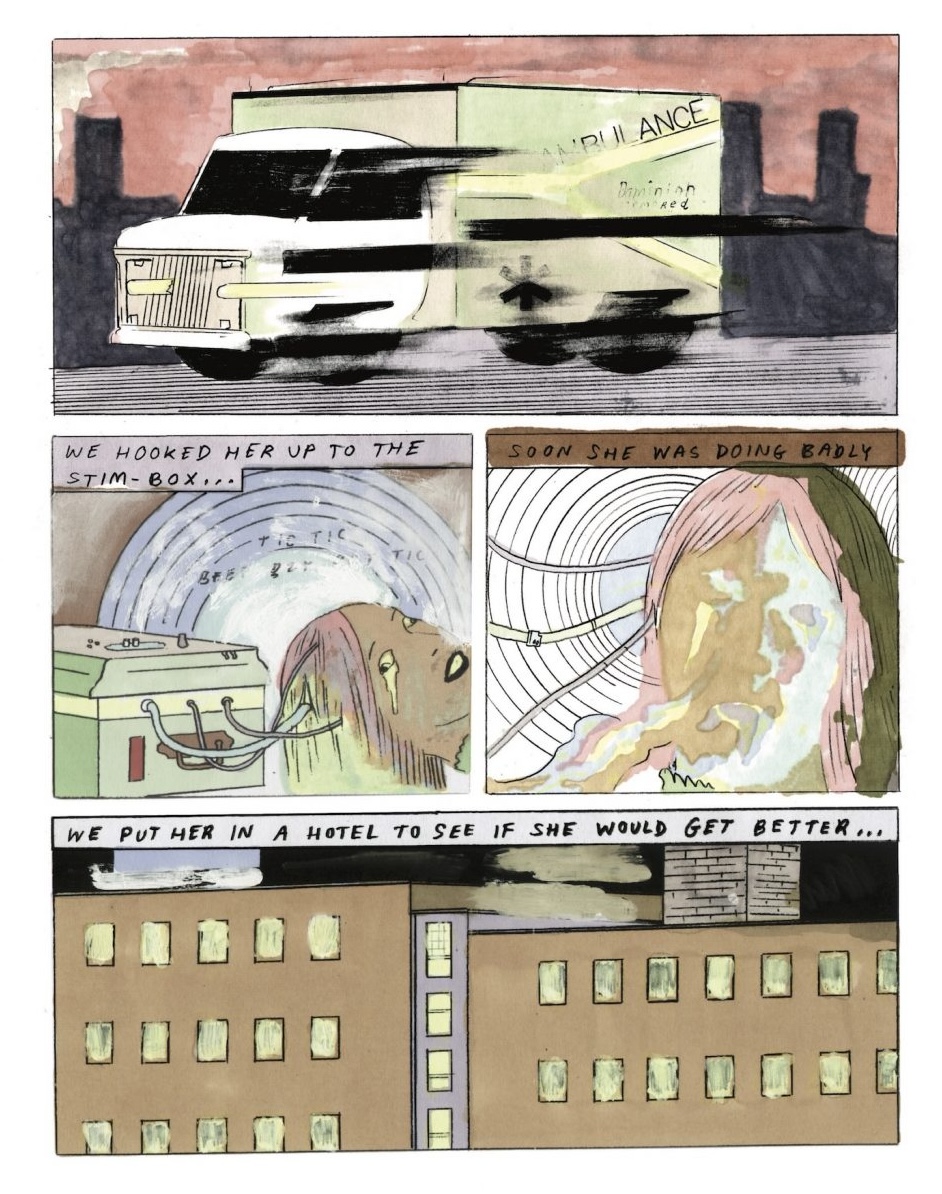

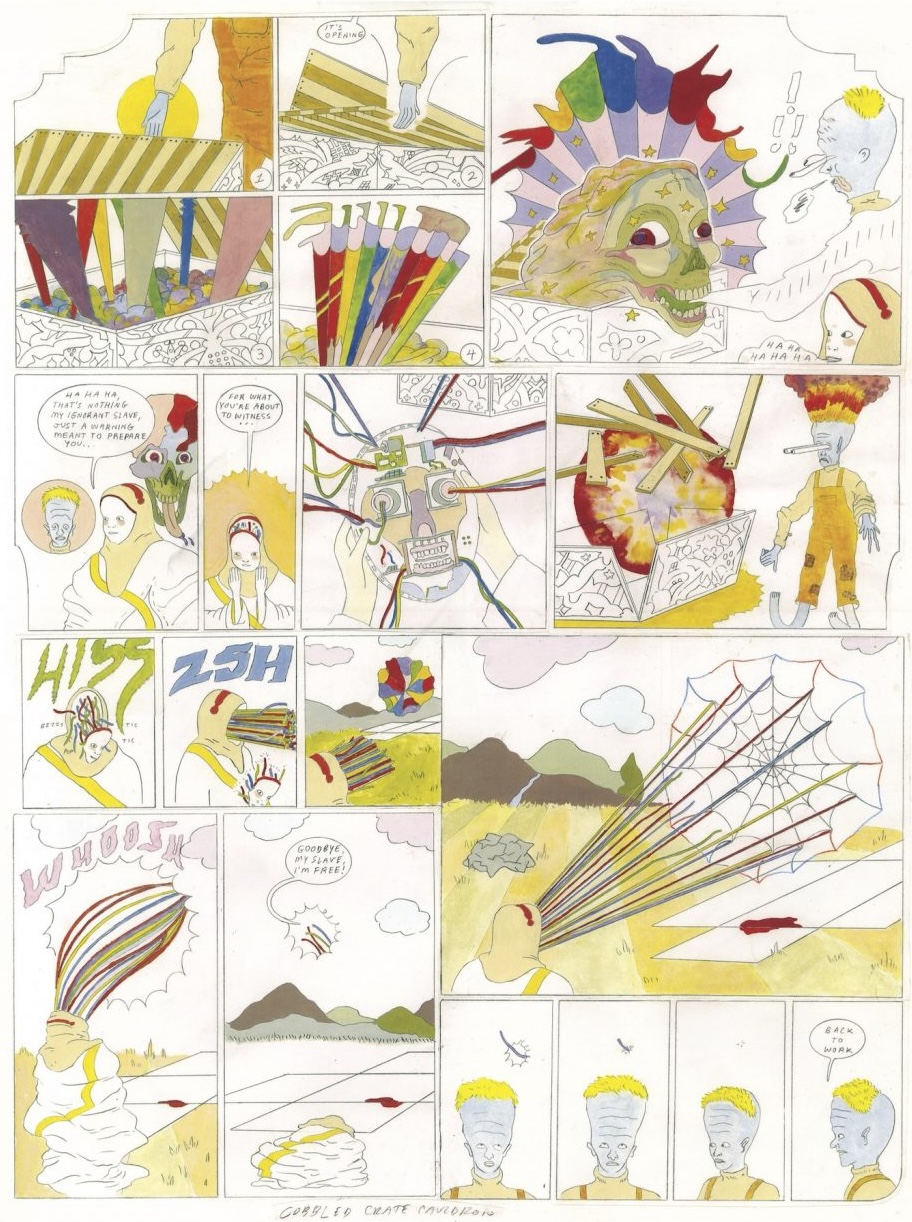

Strips like ‘Dominion Ambulance’ (stunningly inked by comics artist Leomi Sadler), ‘Crate Cauldron’, ‘In The Second’s Lair’, or ‘Del-X’ are perfect summations of CF’s key plot points: breaking and entering, going to someone’s house to collect something, opening a magic box, following your curiosity and doing the wrong thing. And their action always turns on the activation of a strange machine, the unleashing of a psychoactive gas or the projection of metamorphosing energies, vectors of transformation that don’t just change the comic’s characters but the tone and structure of the comics themselves. If there’s a legacy of surrealism at play here it’s of the most dissident, excessive kind: the libidinal line of André Masson perhaps, or the sadomasochistic contortions of Hans Bellmer, even the nonsense apparatus of Raymond Roussel. These comics aren’t just weird, they’re ‘weird, weird’ as Pico Farad, one of Powr Mstrs recurring characters, might say.

In ‘Punk & Hippie’, a 2016 essay for Art in America, Nadel would site the potent yet often unacknowledged influence of CF and Jones’s peculiar aesthetic on a broader popular culture, from TV commercials to pop videos. CF would even lampoon his legion of imitators in the third volume of Powr Msters, writing, ‘I see you people trying to bite my work – disappointing – follow your own star!’, clearly recognising that his approach had been diluted into a new kind of commercialised illustration that tended to misread his deeply considered comics as opportunities for zany graphical one-liners, often pairing science-fiction tropes with deflating normcore captions. It’s the kind of thing we’d eventually come to see in the blandly alternative branding of Urban Outfitters T-shirts, for example, but it’s also possible to see a deeper and perhaps more informed influence in animated shows such as Netflix’s Midnight Gospel (2020), or video games like Sable (2021) or Mouthwashing (2024).

Perhaps Distant Ruptures also marks a good opportunity then to assess CF’s deep legacy and influence in experimental comics, where impressive work by Margot Ferrick (Half Gold/Half Dung, 2024) or Zoë Taylor (Mirror Vault Secret Door, 2024), for example, appear to carry the sensibility of mystery, allusive mark-making and half-hidden references into their mercurial and often wordless panels without toeing any stylistic line. Such exercises are more in keeping with the comics languages developed by CF than any superficial attempt to ‘bite’ his pre-formed style. Indeed, the artist is still as industrious as ever, finding new ways to self-publish through a remarkable Patreon subscription, where comics are printed on endless reams of till roll, hastily scratched out on a monthly basis and thrown straight in the mail. ‘Distant Ruptures’ these works may be, but they set the depth charges that continue to explode our ideas of what comics might be.

Jamie Sutcliffe is a London-based writer, codirector of Strange Attractor Press and editor of Documents of Contemporary Art: Magic (2021)