In Delusions of Grandeur at the Wallace Collection in London, the British artist and ‘national treasure’ pokes fun at the artworld’s hierarchies of class and taste. But is he really in on the joke?

If anyone in Britain can claim to be the nation’s best-known artist, it’s probably Grayson Perry. Perry, the self-avowed “transvestite potter” who popped into the national consciousness when – dressed as his alter ego Claire – he won the Turner Prize in 2003, has in the years since become what would be termed a ‘household name’, even a ‘national treasure’. His knowing and teasing approach to the media, happy to appear on popular TV panel shows while elsewhere producing thoughtful documentaries on questions such as class and masculinity, has made Perry into a ‘personality’. He knows how to pull a wider public, and for that openness he’s acknowledged and embraced by the cultural and political establishment. In 2014 he was elected to the Royal Academy of Art, while in 2019 he was appointed a trustee of the British Museum, and in 2023 he received a knighthood from the King. You could argue that Sir Grayson has figured out, better than most artists and gallery directors, how to address a public outside of the confines of the art ‘establishment’ and its gatekeepers, all while keeping the gate open just enough for himself to move easily between the two worlds. Is he an insider playing at being an outsider, or the other way around?

Perry’s latest show, Delusions of Grandeur, at London’s Wallace Collection – the mansion house which is now a museum for the collection of art and decorative art amassed by a line of English aristocrats during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – is the result of the Wallace’s invitation to the artist to respond to their collection. Inside are portraits by Rembrandt, Frans Hals’s The Laughing Cavalier and endless French baroque and rococo painting, including Francois Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour (1759) and the enduringly ridiculous but stubbornly popular The Swing (1767-68) by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. There are fancy mirrors everywhere, ornate side tables, candlesticks, all of it dripping in gold leaf, much of it from before the French Revolution. You can see why the French had a revolution. And why the English aristocracy, happily un-guillotined, should then enthusiastically buy a lot of this stuff up.

“I don’t love the collection”, Perry says, speaking in his studio a few days before the exhibition’s opening. “If I want to be inspired, I go to the British Museum or the Victoria & Albert Museum. With the Wallace Collection, it’s the stately home thing, and the writhing nudes, which don’t really do it for me.” Instead, Perry tried to find other ways into an artistic response. A book about the ‘outsider’ artist Madge Gill (born in 1882 in London’s East End) gave him the idea of inventing an artist who could be an “intermediary” between the Wallace Collection and himself, and so ‘Shirley Smith’ was born – an amalgam of Perry’s own biography, Gill and the Swiss outsider artist Aloïse Corbaz (born in 1886 in Lausanne). “‘Outsider’ art is an interesting term”, Perry says, arguing that “the artworld, being the voracious thing that it is, has dragged outsider art into its fold very much over the last few decades. So the boundaries have become a lot more blurred.” It’s a term that produces discomfort because “it throws up the question of what is insider art – how do you qualify it?”

Perry is right that the ‘outsider’ artist is not so outside the artworld anymore, having been accorded greater status by curators in recent years, as the stigma of mental illness that often framed the work of outsider artists began to be rethought – a shift confirmed by last year’s Venice Biennale, which showcased both Gill and Corbaz. Delusions of Grandeur mixes works by Gill and Corbaz with works drawn from Wallace’s collections. On display are a series of nineteenth-century aristocratic portrait miniatures; some narrative paintings of women in moments of emotional high drama such as Henri-Frédéric Schopin’s The Divorce of the Empress Josephine (1846), where the titular wife of Napoleon signs away her marriage, while the little emperor and assorted uniformed officers gaze impassively; and pieces from Wallace’s extraordinary collection of weapons and armour – a floridly decorated eastern European flintlock rifle (c. 1630) here, a horned nineteenth-century Iranian helmet there.

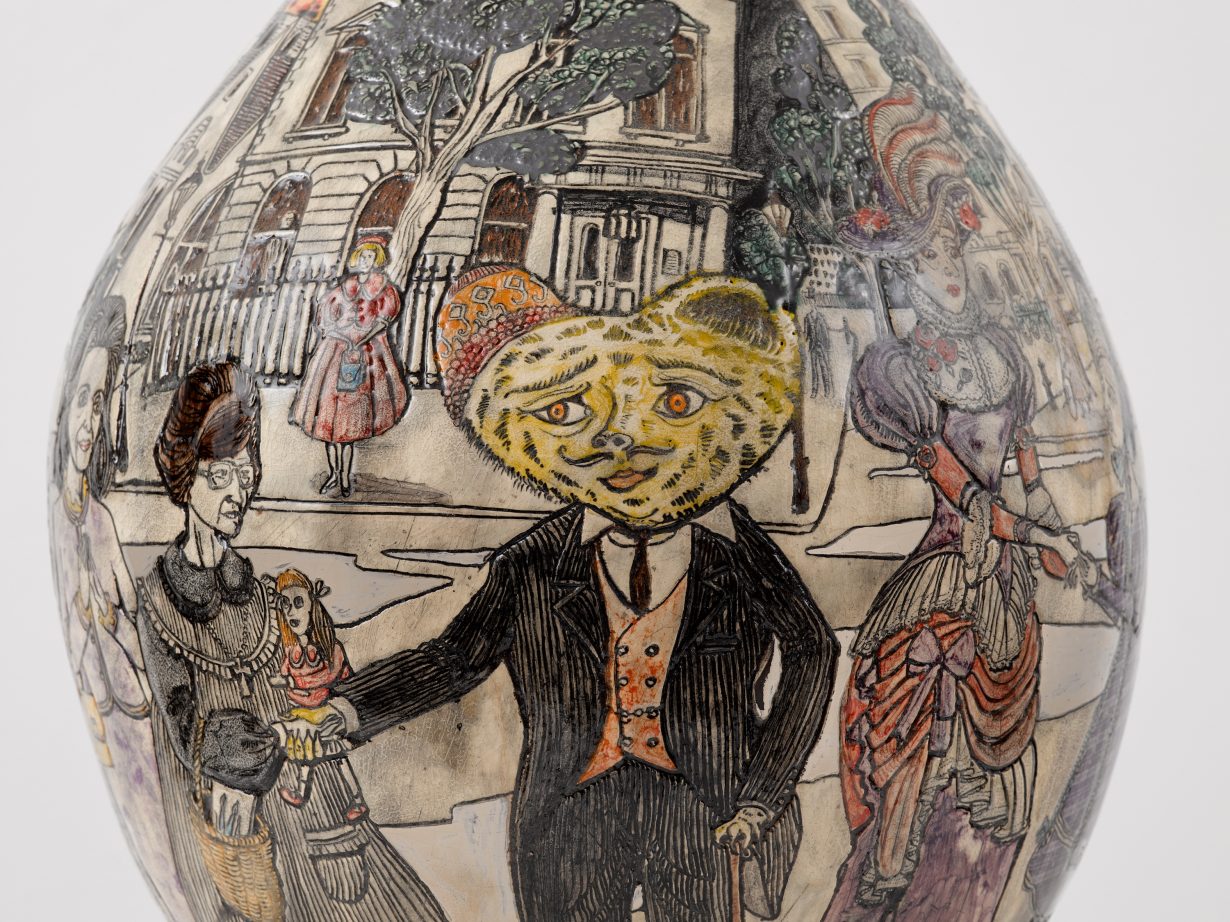

These are interspersed by a new body of work by Perry, many made as if by the fictional Smith. Perry brings in the spectre of the outsider artist, real and fictional, to scratch the itch of class distinctions and power, but, also, through the persona of Shirley, how these gets mixed up with aesthetic fascination and wish-fulfilment: born in the 1930s, we learn that Smith experienced domestic abuse, homelessness and institutionalisation, which leads to her obsessive attachment to the Wallace, believing herself to be Millicent, the disinherited illegitimate heir to the museum. An embroidered textile by Gill explodes with dazzling, haphazard geometries, while her recurring female faces appear and dissolve into the buzzing, warping checkerboard planes that overrun the artist’s drawings. Borrowing from Corbaz and Gill, Perry’s Smith draws bold and cartoonish scenes, in bright reds, pinks and greens, of her fantasy life as Millicent, the wealthy lady she believes herself to be, seen welcoming friends to her rightful home.

It’s colourful and humorous, but Perry’s impersonation and borrowing of these female artists, who were either excluded from the art establishment, patronised as eccentrics and kept at its margins, or locked away in mental institutions, uses the alternative realities of disordered mental health to unpick and satirise the norms of good taste and social order. If this seems a little exploitative on Perry’s part, it does test the fine line between empathic project and self-indulgent fantasy. The recent reintegration of the outsider artist into the artistic canon, though, isn’t of Perry’s doing, and itself points to the complicated power relations between art institutions who welcome in once peripheral and marginal practices while retaining their own power.

Elsewhere, power and marginality are framed through the trope of mental illness. A display of nineteenth-century portrait miniatures – mostly of elegantly dressed white women, and a few men – hangs next to Perry’s etching, A Tree in a Landscape (2024), in which these cameos appear on the branches of a sort of genealogical family tree, but with each cameo titled according to a different mental disorder – ‘depersonalisation disorder’, ‘bulimia’, ‘Tourette’s syndrome’, and maybe a hundred more, all feeding down to a trunk in whose bark we can make out the image of Perry. It’s perhaps a wry and ambivalent commentary on the explosion of mental health diagnosis in recent decades, and the emerging cultural institutionalisation of neurodivergence. Perry’s caption asks whether mental illness is genetically or socially determined, while noting that Smith was obsessed with her genealogy. So were the pasty aristocrats pictured, of course, not least the Seymour family who would accumulate the Wallace collection.

The ironic, sometimes caustic contrast between the outsider artist and social class, insanity and order, refracted through Perry’s own ventriloquising of female experience, makes for a slightly delirious comment on the social hierarchies of aesthetic value and institutional power. While it’s framed as a teasing interrogation of the Wallace Collection’s obsession with the high tastes of the ruling classes of a bygone era, it can’t help but draw its audience quickly back into the current moment, and the way public taste is now ordered by a different set of concerns for power and status. Modern, Beautiful and Good (2024) is a large, psychedelically rainbow-tinted tapestry reproduction of Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour (1759), but over whose empty-eyed, frilly countenance float the logos of major present-day charities – Greenpeace, RSPCA, Shelter, Samaritans. It’s a weird piece, mocking these bastions of contemporary, socially-minded causes by association with aristocratic pomp. In his caption, Perry asserts that ‘rarified culture often feels the need to justify its public funding by hitching the pursuit of beauty to benevolent social causes. Of late, these social and political campaigns have sometimes overshadowed the role of art to deliver aesthetic pleasure’. If that sounds irresponsible and maybe even reactionary, it’s maybe because it hits the nerve that Perry has always been needling: that aesthetic pleasure doesn’t always align with social virtue; that an artist can address a broader public if they find the visual language that connects with it; that opinions, especially in the age of the culture wars, are diverse and often in conflict; and that the artworld is still a place from which certain tastes, pleasures and opinions are excluded.

As Perry reflects on starting out as an artist in the early 80s, “I reacted against the over-intellectualisation of art that was gathering pace at the time, and outsider art offered a template that was away from that, because I think that that over-intellectualisation of art has been to the detriment of it.” There’s a duality in what he does, Perry argues, at once playing to the artworld and refusing to bow to it. “I’m very aware of ‘the artworld’ and its attitudes and cultures. I suppose I treat it like an anthropologist, studying a tribe. The artworld has a certain hubris, but maybe it’s only a little tribe within something bigger.”

Insider or outsider? If anything, Perry’s crisscross of the boundaries reveals that the ‘artworld’ isn’t monolithic, but that it’s made up of different groups and publics, and that some of them have more power that others in determining what gets platformed and shown. It’s perhaps telling, then, that Delusions of Grandeur should be staged at an outmoded old institution such as the Wallace Collection, whose attraction has always been the aesthetic pleasures and permissions that are often played down and sidelined in those bits of the artworld more interested in art that foregrounds particular politics and social agendas – the artworld’s own delusion of grandeur.