The organic and the mechanic come together in the artist’s DIY experiments in robotics

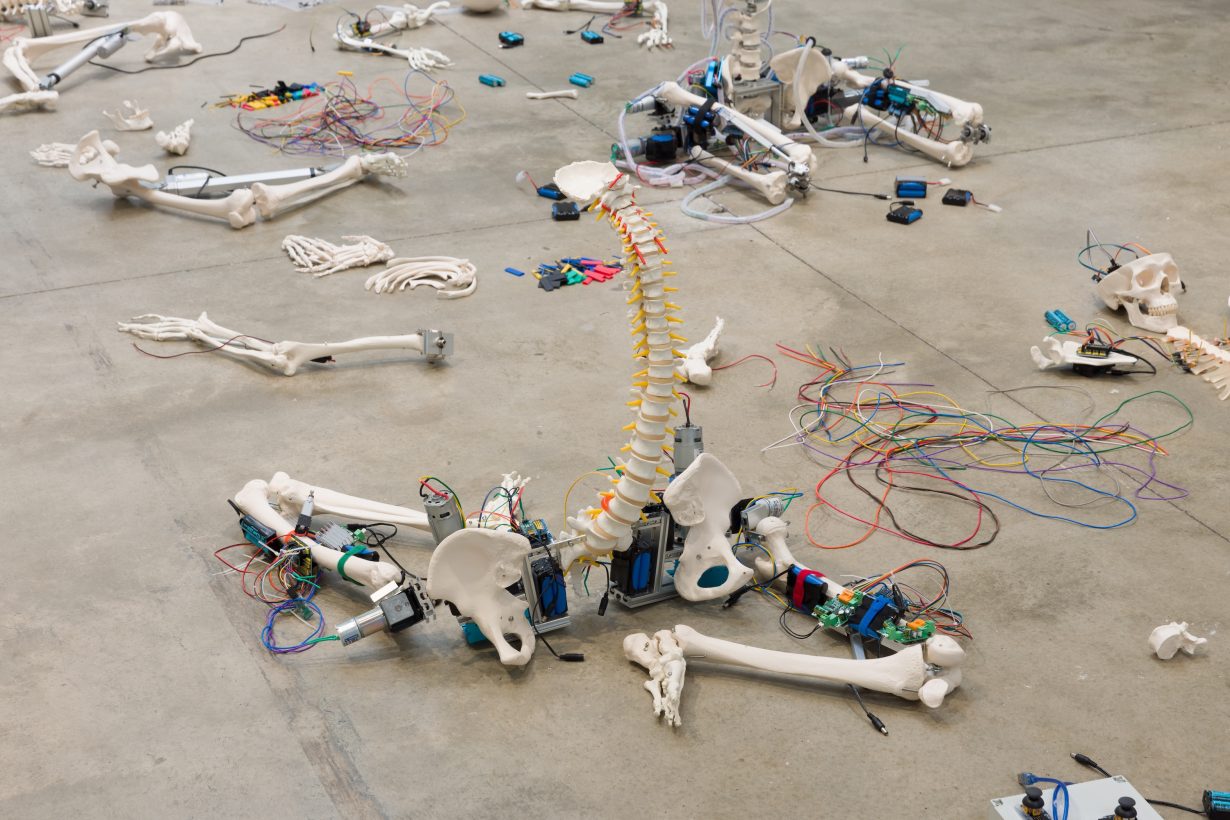

Bleached bones and electronic components are scattered across the centre of the ICA’s bare gallery. On close inspection, these skeletal remnants reveal themselves to be battery-powered humanoid automata (Under Construction (Bodies), all works 2024). South Korean artist and choreographer Geumhyung Jeong taught herself robotics, and her mechanical bodies are here arranged in various stages of completion. The space evokes a curious mix of medical clinic, robot lab and puppet theatre. Though lying motionless, the robots’ legs are extended in expressive postures, eerily suggesting the possibility of movement. Their bones are supported by metal rods and screws, joints sutured with machine panels, while cables, power banks and an array of hardware components are promiscuously entwined with skulls, spines and pelvic bones.

The aesthetic here is resoundingly homemade. Flanking the sides of the machine-skeleton mishmash, Jeong’s collection of DIY electronic components – the tools she’d use to make them as well as plastic skeleton parts – are neatly arranged on six worktables (Under Construction [Arrangement of Unassembled Body]). The setup resembles Jeong’s studio in an industrial manufacturing building in Seoul, and reflects Jeong’s long-running, almost fetishistic interest in collecting worn-out dummies, medical appliances, organlike machine parts and old sex-toys that can be seen in many of her previous works. The ICA installation, though, is the first to incorporate skeleton models. The phalanges and femurs spread across the tables are carefully categorised, reminding one of how, since the advent of clinical anatomy, the body has come to be understood as a collection of replaceable parts, and with advanced medical science, as much interchangeably electronic and mechanical as it is organic. But Jeong’s skeletal figures are hardly futuristic. Instead – crudely assembled on metal skewers and bone plates – they hark back to the genres of outmoded horror films like Frankenstein (1931) and Dr. Giggles (1992; both included in Jeong’s accompanying screening programme), bringing to mind the mad scientist and the butcherlike amateur surgeon of those films, and their obsessive love of unorthodox experiments.

![Geumhyung Jeong, Under Construction [ICA London installation], 2024. Photo: Rob Harris](https://backend.artreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/ICA-Rush-24-September-2024-High-Res-16-1230x820.jpg)

The rear gallery is staged like a sort of control room (Under Construction [Video Room]), with multiple monitors displaying video documentation of Jeong testing her robots in the studio, alongside live footage of the robot installation fed from hidden cameras in the main gallery. While this small, dark room is heavy with a feeling of unsettling intimacy, the closed-circuit video casts a voyeuristic, surveying gaze over the dormant robots and the spectators’ reactions to them. In the videos, meanwhile, we see the robots come to life as the artist assists a lifesize mechanical body, gently adjusting its spine in a gesture reminiscent of a physiotherapist guiding a patient through rehabilitation. In another scene, an automaton crawls forward with an oddly stilted gait, its joints and legs swinging out into uncomfortable positions before it plants itself unsteadily on the ground. Though powered by electronic impulses, these robotic figures’ constant faltering, falling and failing evokes a corporeal vulnerability akin to the fragile bodies of the disabled, the aged, the ailing or the newborn. Their visible struggle for coordination elicits endearing sympathy while teetering on the edge of the uncanny as they so vividly mirror states of vulnerability in the human condition –something usually not expected from machines. In today’s tech-saturated society, where artificial intelligence remains primarily digital rather than mechanical, Jeong’s outmoded automata reveal how humans and machines have become increasingly intertwined. Sophie Guo

Under Construction at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 25 September–15 December