A recent document reveals Israel’s ‘Gaza 2035’ vision, which aims to turn it into a manufacturing hub for the region. We’ve seen this before

Last month, The Jerusalem Post announced Benjamin Netanyahu’s postwar vision for the Gaza Strip, known as ‘Gaza 2035’. It shows a CGI rendering of a futuristic urban enclave, featuring impossibly thin skyscrapers, perfectly manicured gardens, high-speed rail and what looks like lush, arable fields that somehow extend right up to the beach. The artist has anchored a happy little oil tanker nearby, too. The plan involves keeping Gaza under long-term Israeli control, with the document openly stating the goal to ‘rebuild from nothing’ and design new cities from scratch. The renders come from ‘From Crisis to Prosperity’, a Hebrew-language presentation reportedly released by the Israeli prime minister’s office that puts forth the idea that ‘Gaza can become a significant industrial production centre for the shores of the Mediterranean with excellent access to… energy and raw materials from the Gulf while leveraging Israeli technology’.

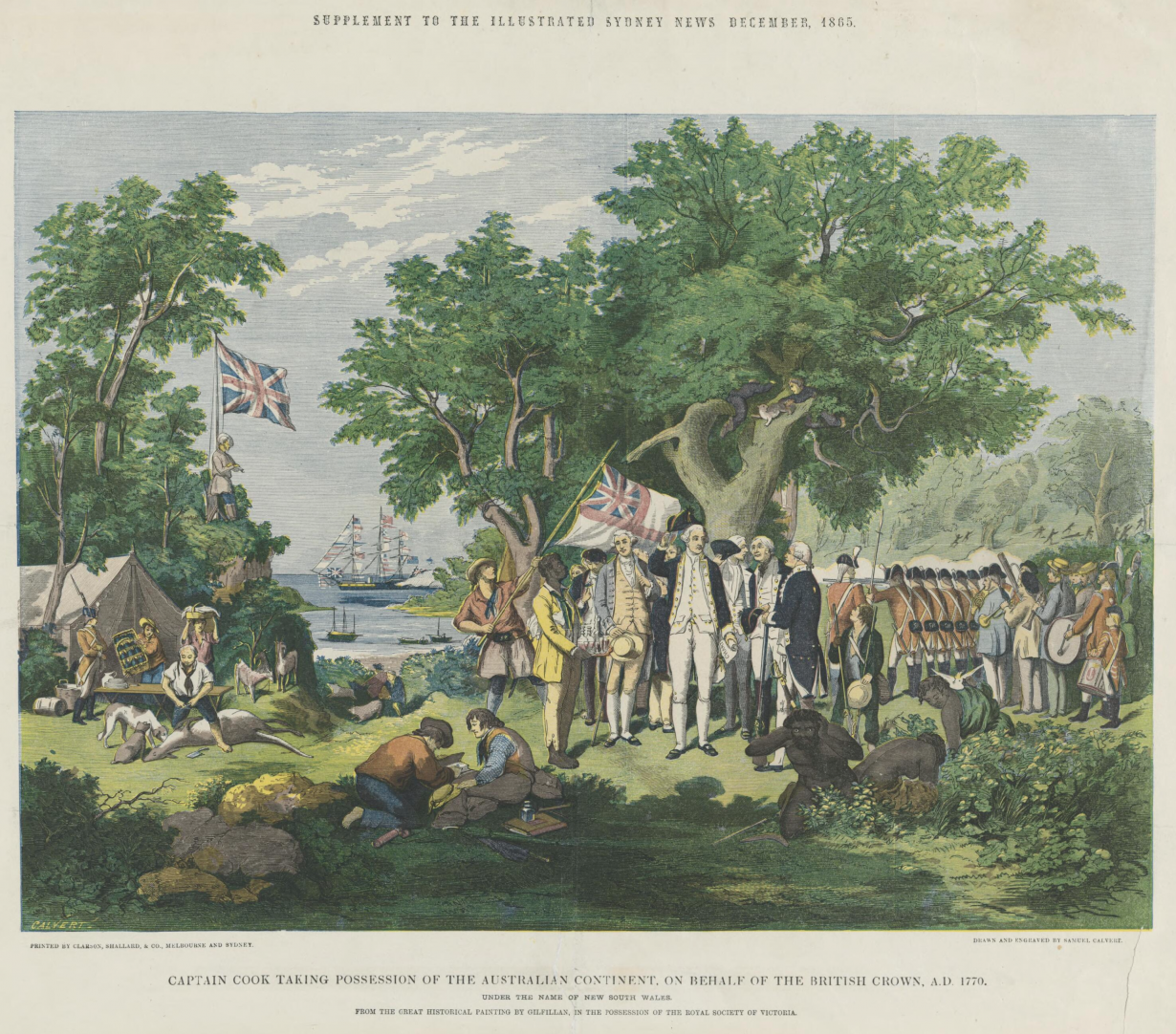

The plan reads straight out of the colonial playbook. Raw materials in, wealth out: the former are turned into commodities by the captive labour of the native population, while its fruits belong exclusively to the occupying power. Much as in 1770 when Captain James Cook landed in Botany Bay, home of the Eora people, and claimed possession of (the continent that in 1901 became known as) Australia for Britain under the doctrine of terra nullius (‘land belonging to no one’). By 1925, British newspapers were writing jubilantly that ‘Australian development’ had seen ‘the establishment of a world trade which now amounts to £300,000,000 per annum… the true spirit of ordered civilisation’.

Cook’s assumption that the land belonged to no one was detached from reality – he had encountered relatively few Aboriginal people in Botany Bay and assumed there were even fewer further inland. But the Gaza 2035 document attempts to create a new reality altogether, counting on all of us to have the memory of a goldfish. Before 8 October 2023, Gaza was already a modern, bustling city. It had a similar average density to London, a 97 percent literacy rate, 36 hospitals, 12 universities, parks, highrises, recreational beaches. If the goal is to ‘rebuild from nothing’, then it will be because Israel has razed the territory’s cities, towns and villages. The question is, who will it be rebuilt for?

A number of far-right Israeli politicians have called for all of Gaza’s 2.3 million population to be forcibly expelled to Egypt or Europe. The Gaza 2035 plan seems, at first, to accommodate some Palestinians within its vision. But throughout the three ‘phases’ explained in the document, it becomes clear that the Palestinians permitted to live among the ruins of their homeland would provide cheap labour in this new ‘regional trade and energy hub’ intended for Israeli business interests. This picture is not unlike the plight of South Asian workers in the Gulf, except Gulf governments have actually been reforming some labour laws recently (with Qatar first to begin phasing out the dubious kafala, or sponsorship, system – the legal framework that requires a local citizen or business to oversee a migrant worker’s presence in the GCC, often leaving workers vulnerable to abuse).

Displacing a population and destroying their existing social, architectural and economic fabric under the guise of modernisation harks back to colonial ideas about certain races and societies being apparently unfit or incapable of extracting the maximum profit from land – an argument favoured by nineteenth-century colonisers from South Africa to North America. Three hundred years of this thinking has landed us in our grotesquely unequal present, yet former colonial powers in Europe and settler colonies like the US continue to finance the militarisation of Israel.

There is nothing visionary about the Gaza 2035 ‘vision’. Devoid of social, ecological and historical accountability, and without even the veneer of interest in Palestinian agency, it is a futuristic facade meant to distract us from the same ambition that drove every colonial power since the nineteenth century: unfettered access to cheap labour and natural resources. To see atrocious images of Gaza being razed, while presented with shiny, state-of-the-art renders of a fictitious replacement – sanitised of everything that made Gaza a home, especially its Palestinian inhabitants – produces a harrowing cognitive dissonance that visual acrobatics cannot undo. These aesthetics seek to seduce viewers with what Israel thinks ‘the true spirit of ordered civilisation’ looks like: an open-air prison where captive labour builds Israeli products at the barrel of a gun.

But the thing with imperial hubris is that, for all of its ruthless calculations, it fails to learn not only from its historic defeats, but also from the woes of its own bedfellows. Israel has a regional ally who has already embarked on a resource-guzzling, futuristic city, but the trials and tribulations of its neighbour seem to have gone unnoticed by the minds behind Gaza 2035. Saudi Arabia’s megaproject Neom, flagged for completion in 2039 but recently scaled back, is another ‘vision’ – indeed called ‘Saudi Vision 2030’ – that rests on similar fantasies of terra nullius. Touted as an ecological prestige project that would render the (allegedly uninhabited) desert an AI-first, car-free oasis, it recently came to light that tribal peoples were displaced – and in some instances arrested – to make way for its construction. The Gaza 2035 vision includes a high-speed railway connecting it to Neom. But there is no terra nullius, and there never was.

Sarah Jilani is a lecturer in postcolonial literatures and world film at City, University of London