Selected by Martin Herbert, associate editor, ArtReview

A repeated motif in Samuel Hindolo’s 2023 exhibition of (mostly) paintings at Galerie Buchholz in Berlin was a figure facing away: refusing, not unlike their maker, to be known. In NUQUE (Neck, 2023), a dark-skinned, ambiguously gendered, beanie-hatted human, a bit mannequinlike, gazes into a tunnel-shaped bit of architecture that other works clarified as the entrance to a subway, part of it seemingly bloodied. In THIRTY PIECES OF SILVER (2023), whose title refers to Judas’s betrayal of Jesus, a grey-skinned character peers rightward into a sylvan landscape at a posing man, while on the left is a ghostly insert of some obscure machinery or mechanism. This dynamic – veiled threat, vulnerable bodies in space, occasional hints of racial violence, the human and the inhuman – is one that the Maryland-born, Bard College-educated, Berlin- and Brussels-based Hindolo already confidently owns, four years after graduation and four solo shows into his career.

Even characterising him as a figurative painter is tricky, since Hindolo paired the gauzily layered, tertiary-rich paintings and delicate drawings in his Buchholz debut with – in the gallery’s adjacent project space – a collaboration with London-based artist Solomon Garçon. This consisted of ominous C-prints of scuzzy rooms (one dirty wall featured the whiter silhouette of a recently removed crucifix; an empty transparent bodysuit lay, phantasmal, on a flight of stairs) and a soundwork comprising ghostly knocking. Religion and the spirit world might thus begin to suggest themselves as supplementary themes, but – as in the story of Jesus and Judas – what here seemed to count more for Hindolo was the figuring of incoming, unpredictable turmoil, in a manner that speaks to a world on edge, holding its breath. His default is allusive, inhabitable suspense, constantly dropping the viewer into an unclarified narrative. So far, Hindolo appears to have done no explicating interviews, and I’ve only found a single, unofficial photograph of him. But he does write his own handouts. In the one for this show, he grounded his practice inferentially in the present and near future: of PETER, JAMES AND JOHN SLEEPING (2023), a painting of Christ’s disciples drowsing while military figures move past them, he noted that ‘being adrift gives them the sense that they’re elsewhere in some prolonged retreat from the present when in fact looming in the distance is something else’.

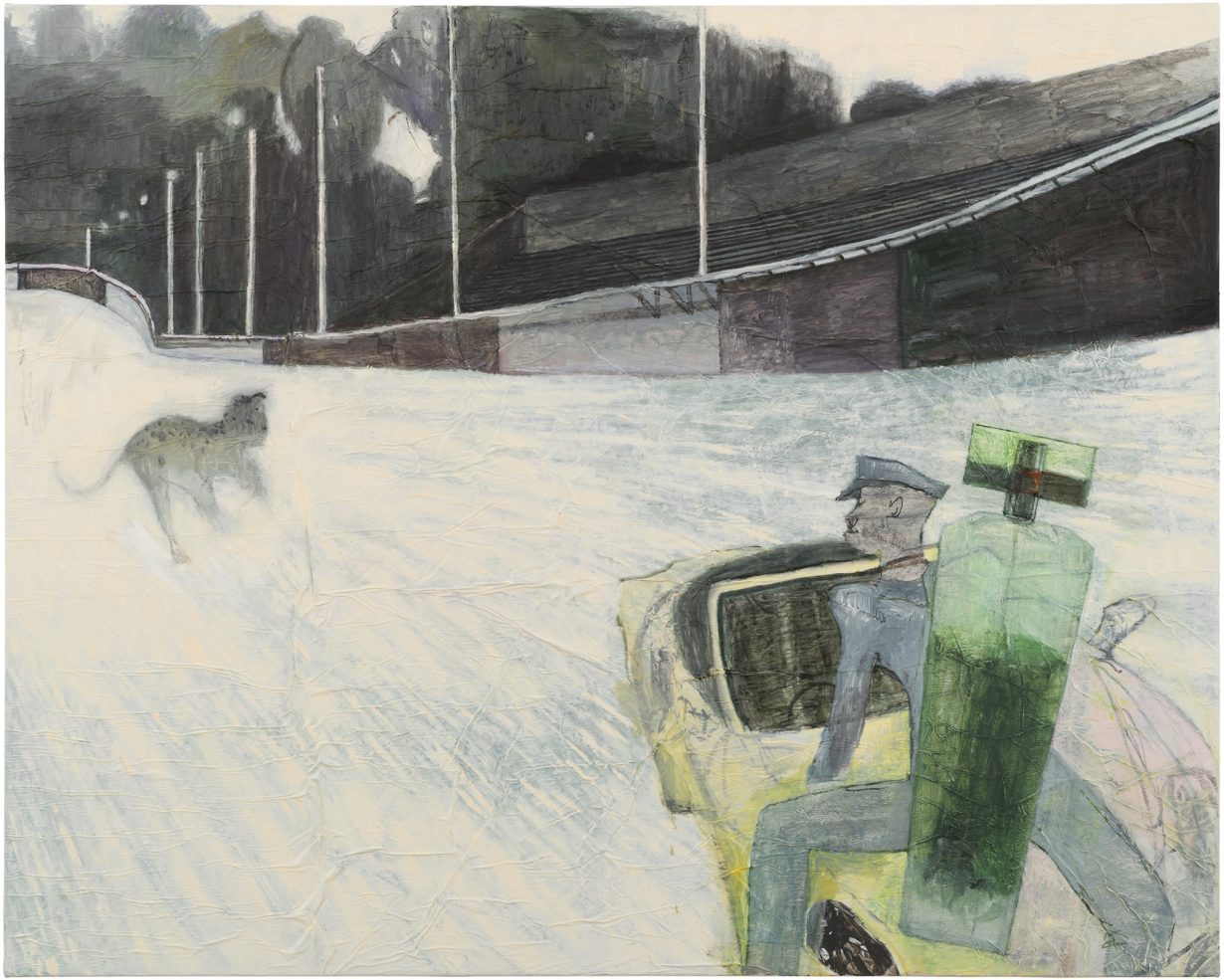

For the 2024 exhibition EUROSTAR in New York – split between Buchholz’s Upper East Side gallery and Tribeca space 15 Orient – Hindolo referenced SAÏDA MAKES OFF WITH THE MANNEKEN PIS, Alfred Machin’s 1913 short silent comedy about a leopard that escapes from a circus in Brussels, causes havoc and knocks down the eponymous statue, Belgium’s national symbol. Authority, implicit Africanness and toppled statuary are in the mix – one drawing depicts the big cat smothering the pissing boy – pulling the film forward a century and more, albeit in scrambled fashion. In one scenario that recurs insistently as collaged photocopy studies, drawings and the oil-on-paper SAÏDA (TWO SCENES, ONE PREDICAMENT) (2024), the leopard is pursued on a velodrome by police. There’s also a giant bottle of perfume in there, and social-media postings by Buchholz when the show opened suggested (as Hindolo’s press release didn’t) that perfume mattered here because of its ephemerality, the artist specifically bending it to speak of Empire: one collage displayed perfumes named for Napoleon and for Léopold Sédar Senghor, the first president of newly independent Senegal.

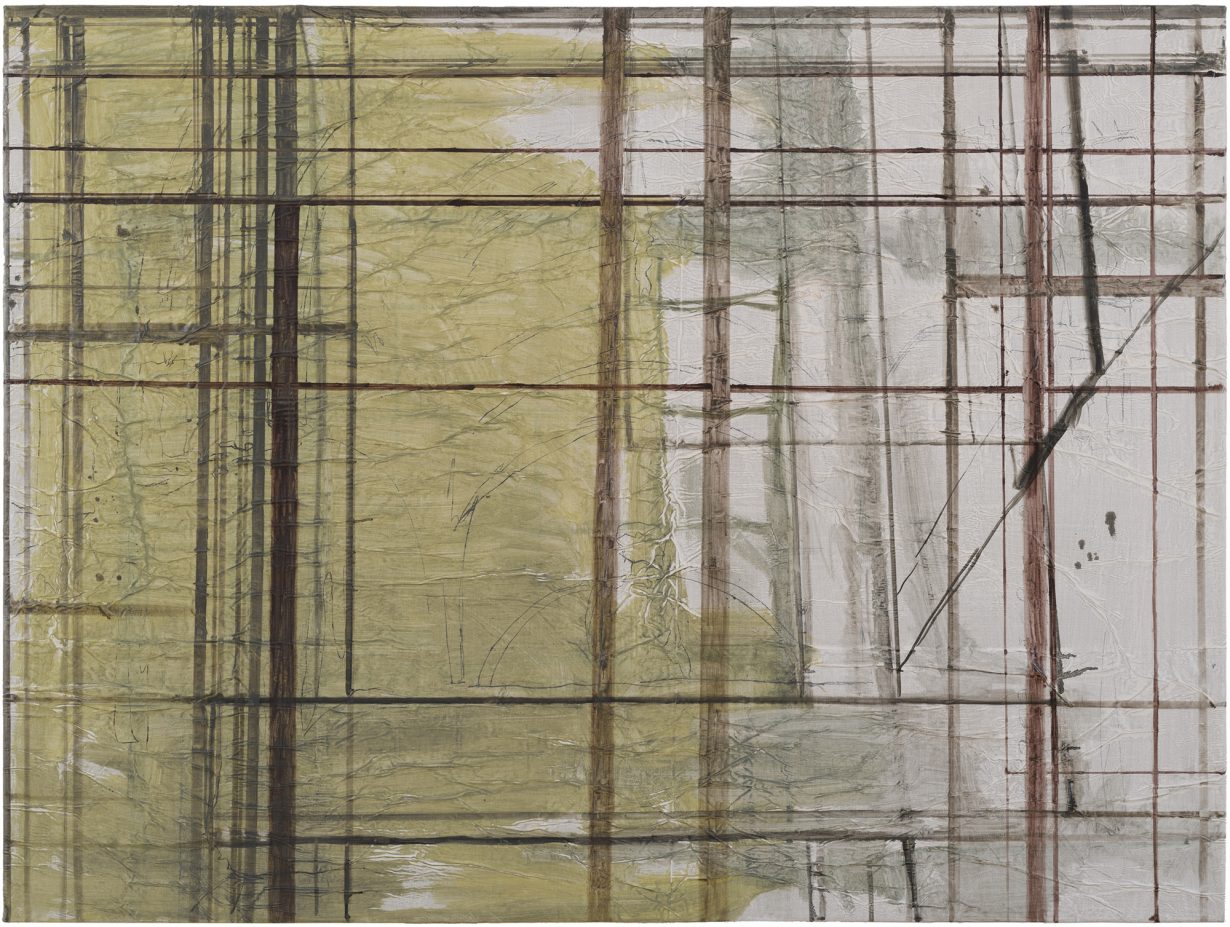

Meanwhile, adding to this halfway-decodable poetics, abstract canvases composed of wobbly layered grids referred in their titles to science-fiction writer Bob Shaw’s 1966 notion (in his short story ‘Light of Other Days’) of ‘slow glass’, through which light takes years to travel. In the context of EUROSTAR, the notion of something happening slowly (and of things that fade like old perfume) might be read a few ways: through the history of imperialism undone and of postcolonialism’s evolution, but also through how that narrative’s threads are themselves subject, here, to a delayed braiding-together, since Hindolo is not about to make his art easily consumable. Rather, in an era of often issue-driven figurative painting that hits quickly and expends itself, he builds unhurried, probing, effort-requiring scenarios and to an extent seems to be reinventing, show by show, himself and his work’s codifications. Both his art and his career accordingly raise the same insistent question (and make this viewer, at least, keen to know the answer): what happens next?

Samuel Hindolo is an artist based between Berlin and Brussels, working across painting, video and sculpture. He obtained a BA in Studio Art from the University of Maryland in 2012 and an MFA from Bard College in 2021. He recently had a solo exhibition at 15 Orient and Galerie Buchholz in New York.