Edited by Michael Part and Constanze Schweiger, Verlag für Moderne Kunst, €26 (softcover)

Reviewed by Ben Street

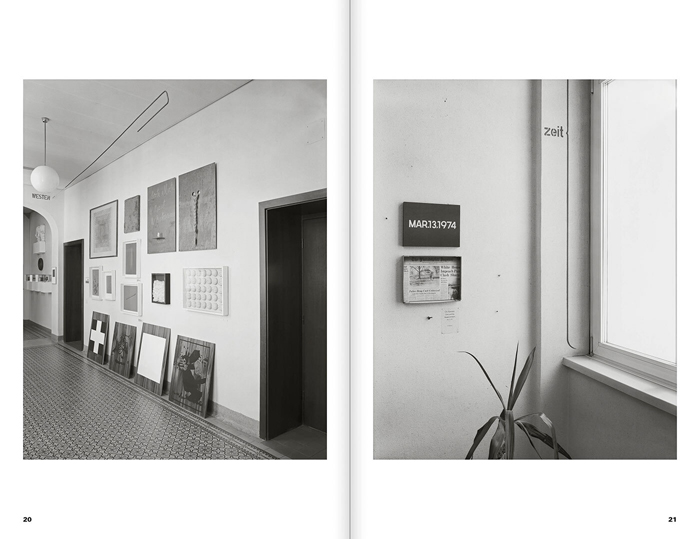

The self-reflexive new hang of London’s Royal Academy, in which the plaster casts of classical statuary used for centuries as the basis of artistic instruction are displayed as objects of interest in their own right, reveals the gulf between art education then and now. The faithful reproduction of the three-dimensional object on the page, once the route by which any artist might develop the skills needed to go professional, is now a curio of the distant past. That said, appropriation as artistic practice is itself now traditional, even academic, making Franz Parts Schule, an appraisal of artist and teacher Franz Part’s pedagogical activities, timely and potentially fruitful. The book is an assemblage of texts by artists and curators reflecting on Part’s approach, from essays by Marina Gržinic and Ilse Lafer, to two suites of photographs by Simon Starling and Hannes Böck, along with fragmentary texts by filmmaker and artist Kerstin Cmelka. Part worked as head of the art department in the Bundesgymnasium and Bundesrealgymnasium (for ages ten to eighteen) in Waidhofen an der Thaya in northern Austria for almost 30 years, starting during the late 1980s. Starling’s photographs of the school’s interior evince a double take: every wall is hung with scale reproductions of canonical twentieth-century art. Man Ray’s cloud of coat hangers swings above a stairwell; there’s a Jackson Pollock in the corridor, a Keith Haring by the ping-pong tables.

Part began the project by making reproductions of works by Marcel Duchamp, whose indifference to the value of the original, reflected in his endorsement of replicas of his own work, is the evident guiding spirit. Hung in public areas of the building, Part’s objects, displayed alongside conventional museum labels, drew interest from the students. They quickly became involved, using found materials to work with Part to produce exact replicas of works by Duchamp and his heirs (Joseph Beuys, Marcel Broodthaers), high-modernist abstract painting (Kazimir Malevich, Sophie Taeuber-Arp) and postmodern conceptual art (General Idea, Art & Language). The result, filling the staircases and corridors of the school, became known as ‘The Museum of Replicas’, and was (and is) arranged by artist or genre. The status of these collaborative reproductions – as pedagogical tools, conceptual acts or what Cmelka calls, in her writings in the book, ‘cover versions’ – remains open, but their physical context within the public spaces of the school means they speak with unexpected clarity to the actual lived experience of education. Seldom have On Kawara’s deadpan paintings recounting a specific date, or Joseph Kosuth’s presentation of the dictionary definition of a chair alongside an actual one, felt so perfectly placed, capturing as they unwittingly do that feeling of time’s endless stretch in a boring lesson. At times the ‘Museum’ seems to run alongside the life of the school as a critical commentary on the nature of learning itself.

How the students themselves engage with these works, however, is a notable absence in this book. Despite being made collaboratively, the reproductions’ authorship is always given to Part himself, thereby reviving a culture of mastery you’d assume the project existed to question. A perhaps obvious comparison with Tim Rollins’s KOS (Kids of Survival) project (founded 1982), in which Rollins and his students collaborated on works of art that grew directly from classroom discussions, sees Part’s approach, at least in the form presented in this book, fall short. Böck’s beautiful series of photographs, taken systematically on every floor of the school, show corridors zooming into the distance, each one dense with artworks – but they are empty of students, as ideally noiseless and unpeopled as an installation shot of a white cube gallery space. That aside, the implications of Part’s practice bear consideration in the current culture of anxiety around the status of the arts in education. A revival of that long-derided culture of copying might reengage students with the values of creative labour – or at least provide a realistic skillset for a career in fabrication. And in doing so, works of art might themselves benefit by being reenergised through reproduction, and gather new energies through acts of attention and transcription.

From the March 2020 issue of ArtReview