In Patternmaster, the artist entangles her viewers in a web of cultural associations that reflect their own biases back at them

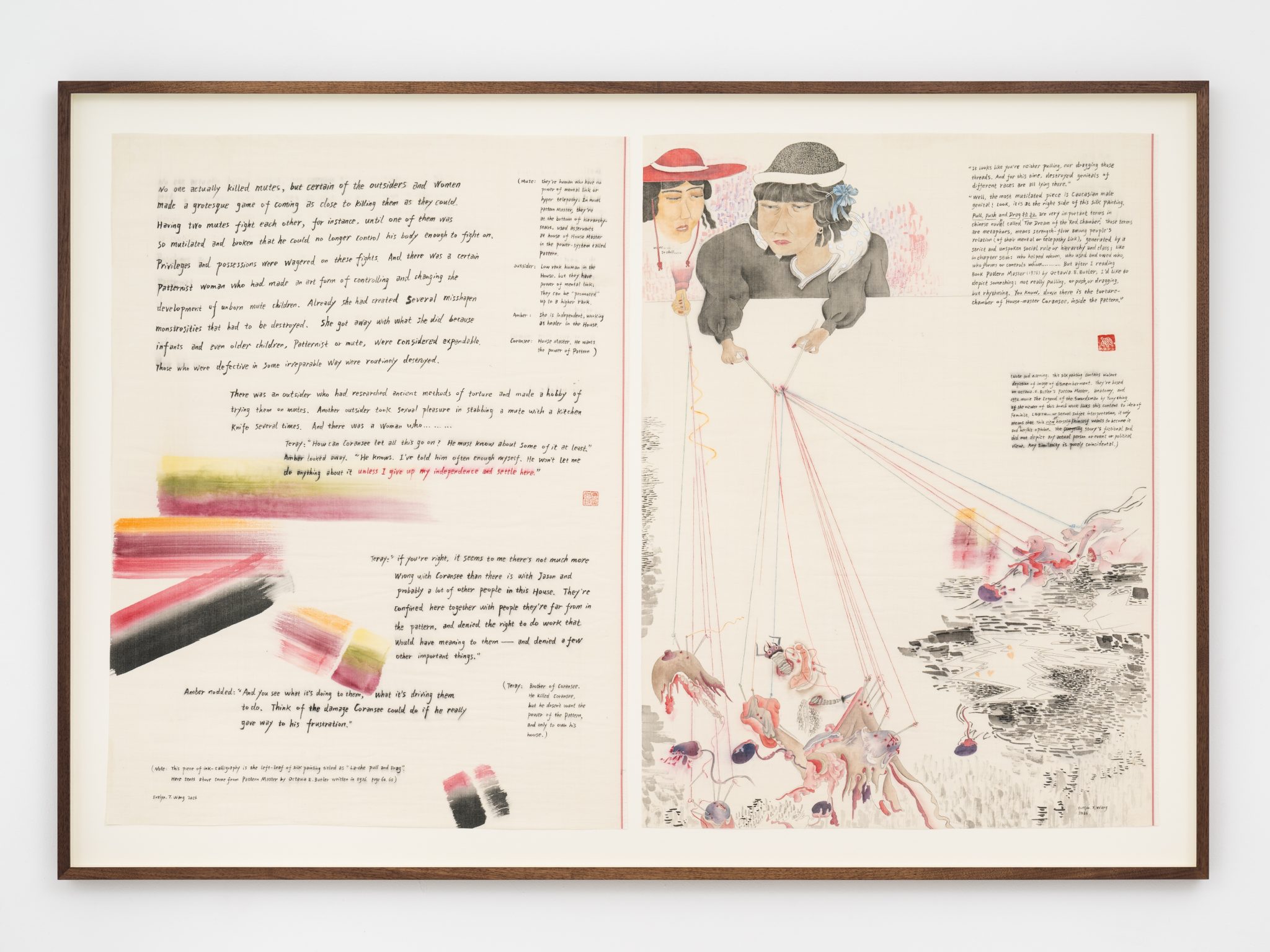

Evelyn Taocheng Wang’s Pulling Pushing Dragging (all works 2024), a diptych painted on silk, features a calligraphed extract from Octavia Butler’s 1976 novel, Patternmaster: ‘No one actually killed mutes, but certain of the outsiders and women made a grotesque game of coming as close to killing them as they could’, the quote begins, prefacing a story of control and violence. A painting of two women – at once seamstresses and puppet masters – holding mutilated creatures and organs on the end of multicoloured threads completes the work. Throughout the exhibition, a game of call and response between text and image takes place on canvas and invites us to reflect on interpretation and the power that lies in controlling meaning.

The Diagram series displays swatches of graded colours, recorded to distinguish different mixes of paint and their connotations. ‘White means… Frans Hals painting, facial powder…’, we are told. ‘Water means… Chinese ink-wash painting, tea…’ The absurdity of Wang’s statements, which create false equations between technique and meaning, questions the objectivity with which Western art-history informs our knowledge. The inclusion of national and regional categories within these word associations highlights how cultural differences between East and West become engrained in these taxonomies. Continuing to build on art-historical references, three works in paint and pencil on canvas are, their titles or annotations indicate, imitations of Agnes Martin. Yet each abstract composition is disturbed by symbolic eruptions. One work features a winged lion holding a mirror, Wang’s interpretation of a creature from Butler’s novel. Across the room, in Teray’s End, a princess frog, gender-bending the fairytale cliché, emerges from the background. These visual and textual quotations, a mix of literary and historical references, provide splattered data–points that bait us into attempting to discern the works’ meaning. But pandering to the viewer’s desire to analyse, Wang breadcrumbs interpretations that seem only to lead us back to our own knowledge and biases.

‘If the viewer of this brush work links this content to idea of feminist, LGBTQ… or sexual subject interpretation, it only means that this viewer herself/himself wants to become it and is his/her opinion’, claims the text on Pulling Pushing Dragging. The fallacious logic emphasised by the awkwardness of second-language English playfully claims to distance Wang from her role as maker-of-meaning. Simultaneously, several notes harbour content warnings parodying legal disclaimers – ‘this silk painting contains violent depiction of image of dismemberment’, for example – pointing to a more brutal aspect of the works. Most of the paintings contain a kaleidoscopic gore of animal flesh and surgically threaded genitals. What seem like mushrooms rendered in a classical Chinese style turn out, on closer inspection, to be dismembered penises strewn across the canvases. Such double takes subvert stereotypes around the artist’s identity as a Chinese woman and remind us that, despite what the warnings may lead us to believe, Wang remains fully in control of the narrative she depicts: one about the seamless violence of cultural hegemony.

Teray’s Empty World, Raw Chicken Legs leaves us with a final trick. The absurd and beautiful painting of a plate of raw chicken set against an abstract background is complete with stage instructions at the top of the canvas and, rising from the bottom edge, a pair of hands – our own? – poised as if about to clap. ‘Oh wow, let’s applaud in front of this raw chiken-legs!’ reads the artist’s text. As we read the script in our minds, we become the unwitting actors of her play. It makes us wonder: who is really pulling the strings here?

Patternmaster at Carlos/Ishikawa, London, 21 November – 21 December

From the January & February 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.