Celebrity authors are rebranding themselves as philosophers of art; an extraordinary dumbing down of culture has occurred

This January saw the publication of musician Brian Eno’s What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory, the latest in a line of patronising books by celebrity authors who have rebranded themselves as creative gurus. Essentially a picture book for adults, What Art Does shares Eno’s limited concept of art using supposedly kooky graphic design and infantile illustrations. Pearls of wisdom include: ‘The less functional a thing is – the less it has to do something in particular – the more space for art there is in it’, an idea accompanied by a diagram comparing how much ‘art’ there is in a thing to how decorative a hat is. At one end of the spectrum is a rudimentary drawing of a man wearing the helmet of a diving suit – completely functional, according to Eno, and therefore in no way art. (Try telling that to Dalí, who came dressed in a deep sea-diving suit to the London International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936, or to adherents of the Bauhaus ‘form follows function’ motto.) But the hat with the feather in it? That definitely counts as art. No need to get bogged down in anything as bothersome as context, which the author and publisher have apparently decided is much too complex for the readership to comprehend. Eno ends the book in exemplary ‘gather round children’ style, using Giuseppe’s Penone’s series of tree sculptures to explain how creativity reveals our inner infant: ‘Inside big tree is baby tree. Inside you is little you. It’s always there.’

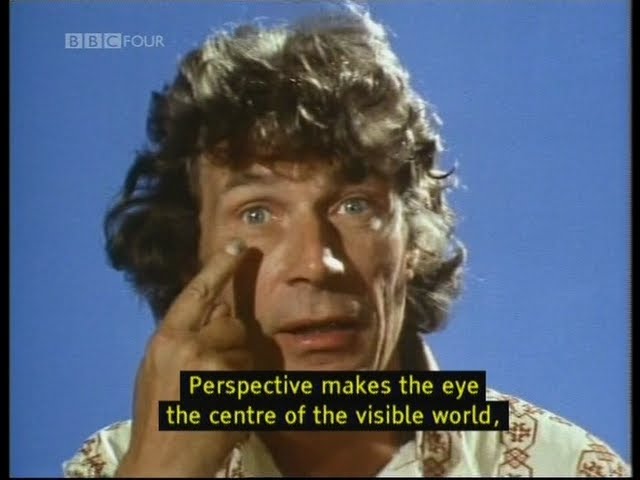

Eno is not the only music industry celebrity attempting to reposition himself as a creative guru. Enter Rick Rubin, founder of Def Jam Recordings and one of the most successful music producers of recent decades, who has helped define the sound of everyone from Lady Gaga to Johnny Cash. Rubin has decided his talents do not stop there. His 2023 book The Creative Act, which aims to reveal the quasi-spiritual mysteries of creative genius its author has unlocked, is awash in the kind of corny new-age affirmations you might expect to find on the Goop website. ‘Think of the universe as an eternal creative unfolding’, Rubin muses. ‘Just as trees grow flowers and fruits, humanity creates works of art.’ Some parts of the text are organised like poems, others in short chapters, the entire thing straining so hard to be profound that you can almost feel the piles forming on the pages. The idea of taking your audience by the hand to bring them to a higher level of understanding is certainly nothing new. We might think of the ‘kindly teacher’ tone in which John Berger wrote Ways of Seeing, or Kenneth Clark in the series Civilisation, a tweed-clad elder statesman instructing viewers on the evolution of art history. Yet unlike their forebears, Eno and Rubin assume precious little of their readers’ cognitive capacity, ignore centuries of thought, and instead opt for the lucrative language of self-help and wellness.

In this regard, both Eno and Rubin are indebted to Alain de Botton. Son of a Swiss banking magnate, De Botton fashions himself as a humble cultural shepherd benevolently guiding his pure-hearted but downtrodden flock to a more enlightened way of being. Through his business The School of Life, which has locations in London, Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam and Sao Paulo and has reportedly made De Botton millions, devotees can pay £3000 to go glamping with psychotherapists, buy £26 packs of cards printed with excruciating ideas for conversation starters – ‘describe an early sexual encounter’ is a particular toe-curler – along with books explaining everything from religion to sex and art. Expediently, given the self-help nature of his business, De Botton argues that art’s role is therapeutic, and that it should be treated as a tool for improving our day-to-day lives. He expounded upon this idea in his 2014 book Art as Therapy – and in his ‘intervention’ at the Rijksmuseum that same year, where he added giant Post-it notes to artworks, some with text presuming to speak on behalf of viewers by describing what they are thinking and feeling, others attempting to make masterpieces relatable by posing banal questions. ‘I can’t bear busy places – I wish this room were emptier’, read one placed next to Rembrandt’s The Night Watch (1642), surely a contender for the least insightful thing ever said about a work of art. ‘If the artist were making it for you, what changes would you ask for?’, read another stuck to the plinth of a cast of the Laocoön. Rather than using art to enhance our understanding of ourselves, history and the world around us, de Botton proposes a stunningly unambitious model of engagement, reducing art to a means of validating prosaic complaints and covetousness.

What can we glean from these recent additions to what, at a stretch, might be called the philosophy of art? For starters: the current dire state of the publishing industry, which continues to favour the selling power of celebrity over specialist writers and thinkers. It also indicates just how low the perceived level of popular understanding of art is – and how little is expected of an audience’s intelligence.

An extraordinary dumbing down of culture has occurred, smuggled in via the promise of inclusivity and anti-elitism. The now-commonplace association between intellectualism, seriousness and snobbishness effectively places preconceived limitations on what people are capable of understanding, a model that stymies ambition and speaks down to viewers and readers. As such, it is not really anti-elitist at all, and is only inclusive insofar as nothing much is expected of anyone. Outside of the silo of art publishing, itself often preoccupied with appealing to the luxury commercial gallery sector that helps keep it afloat, public conversation about art is almost exclusively limited to news stories about NFTs and AI, hooked to artists who have managed to break through to the mainstream by positioning themselves as media personalities, or – as is the case with Banksy – creating the kind of feverish hype and speculation whipped up by brands.

Rubin’s and Eno’s roadmaps for creativity – and De Botton’s empire – are also made possible by a wider crisis surrounding the role of art in society, and a concomitant need to justify and explain its existence. If once art was in the business of venerating God, or – as it was during the modern era – pursuing the horizon of artistic ‘progress’, today its purpose is so broad that it can be, well, anything at all. This apparent boundlessness has contributed to a panic regarding what art should do and who it should serve. Should art help solve societal problems? Should it tell the truth? Must it be for everybody? If it isn’t, does it even deserve to exist at all? Should we get rid of the art object entirely?

Into this maelstrom of doubt come the great pretenders, ready to exploit the mood of anti-intellectualism by reframing ignorance as a virtue and plump their egos by assuming the role of benevolent masters. Art, of course, is far more interesting and complex than whether or not you wear a feather in your hat. It is certainly more challenging than silly diagrams or trite self-help jargon, there to comfort us about our own shortcomings. Corny celebrity art gurus are merely a sign of the times. Until cultural intelligence is again viewed as something of value – something that (yes!) anyone can aspire to – they will continue to flourish, feasting on the corpse of public discourse.

Rosanna McLaughlin is a writer an editor. Her forthcoming book Against Morality is published by Floating Opera Press in 2025