Six months after the June referendum result in which British voters surprised the world by voting to leave the European Union, nothing much has, in fact, actually happened, other than a slumping currency. The initial panic of the political establishment has now settled into a pattern of awkward procrastination by prime minister Theresa May’s conservative administration, much of it down to dragging out the schedule for the enactment of Article 50, the treaty mechanism which will trigger the process of terminating the UK’s membership in the EU.

Many in the creative sector were loudly dismayed by the Brexit result, fearing, like many pro-remain supporters, that it signalled the return of a xenophobic, even racist Little-Englander retrenchment. Others were fearful that it heralded an unprecedented and risk-filled leap into the unknown, with unforeseeable consequences for the economy and European stability itself. But since the initial upset, the art community seems to have had little more to say. A muted gloom now seems to hang over much of the cultural sector, while the most vocal responses have been pragmatic declarations focused on making the most of the situation, largely coming out of the commercial side of the creative industries. So the UK’s Creative Industries Federation has issued a report of recommendations about free movement of skilled workers and students, and protecting intellectual property; elsewhere a ‘Brexit design manifesto’ has been announced, signed by dozens of leading British names in commercial design and art, making similar demands.

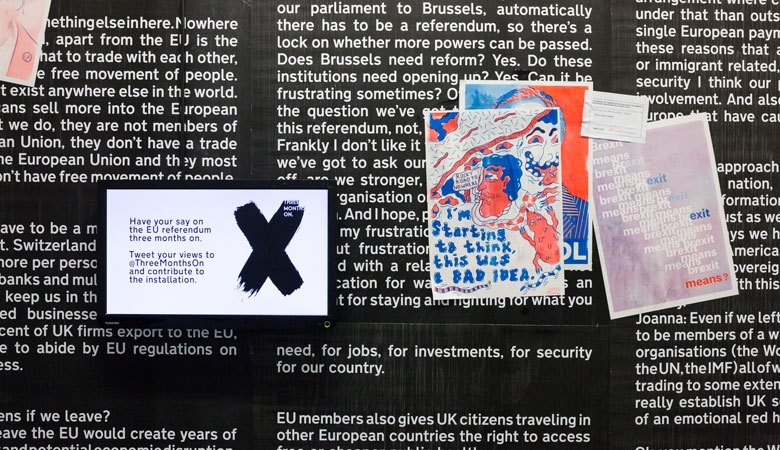

But as for coming to terms with why more than half the country voted to leave, few seem willing to really go beyond the earlier clichés about a ‘deluded’ or misinformed British public, or how to relate to the 52 percent of the country who appear indifferent or hostile to the European project. It’s perhaps not surprising that the most open response has come from those parts of the cultural world with the biggest stake in the idea of a national culture; Rufus Norris, artistic director of the National Theatre, pioneer of ‘verbatim’ theatre, announced in September a major ‘listening project’ for the National titled ‘Missing Conversations’. Interviewers will record the opinions of ordinary people across the UK, and writers and theatre-makers will be commissioned to work with the resulting material. As Norris put it bluntly in September, “I don’t believe 17.5 million people are racists or idiots… I think we’ve got to listen.” Among contemporary artists and institutions, there have been a few halting responses, again outside London, where artists and institutions have to deal with the reality of their local public having largely voted leave. Derby’s QUAD art centre, for example, invited a print workshop, Dizzy Ink from neighbouring Nottingham, to produce an evolving exhibition of posters, designed in collaboration with members of the public. But such initiatives are few and far between.

The problem of trying to figure out how to develop a dialogue with the leave-voting public has put into stark contrast the remoteness of contemporary art from a wider public, which, especially outside the big metropolitan centres, gets served a certain view of art and the world emanating from metropolitan art culture, with little exchange of views. As artist Liam Gillick, writing in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in July, observed of the slogans generated by pro-remain artists such as Wolfgang Tillmans, ‘in retrospect, however well-intentioned these slogans may have been, they seem weak in the face of an entrenched suspicion of bureaucratic Federalism and a distrust of warm statements of togetherness emanating from a metropolitan elite.’

That voters in the referendum upset the mainstream narrative favoured by those who see Europe as a ‘warm statement of togetherness’ at the very least shows up that contemporary art, even if it sees itself as politically and socially engaged, nevertheless does so from the perspective of a relatively narrow cultural and social demographic. Dismissing half the country as misguided or ignorant doesn’t make you a lot of friends. That artists and ‘creatives’ should all uniformly agree on an issue seems more like an exercise in group-think than creative thinking, or an openness to dialogue which art is supposed to celebrate. If art’s engagement with society is to mean something credible, it’s time to have a conversation – to speak, and to listen.

This article first appeared in the December 2016 issue of ArtReview