You know what? I don’t care that a painting by Modigliani – Nu couché (1917–18) – just sold for $170 million at auction. Yes, I know, I’m supposed to offer up a fierce denunciation of the out-of-control art market and its megacollectors. Because that’s all us critics seem to do these days, in a time when the critical consensus, wherever you go, tends to be a rankling frustration with the spectacle of the art market, its glittery novelties and totemic antiques, and its bizarre hold on popular consciousness. And while political debate is fixated on the excesses of the so-called one percent, on apparently ungovernable financial speculation and on growing inequality, the default response is the vaguely manic-depressive feeling that, in the end, there’s just nothing ‘we’ can do about it.

But those are the received ideas of our time, and I don’t buy them. I don’t buy them because, rather than stellar art-auction prices and torrents of financial liquidity being signs of excess, of there being too much wealth, they’re signs of the opposite: it may sound weird or even slightly heretical, but rather than too much wealth, there’s just not enough of it. Let me try to explain.

Too much of current economic debate has a schizophrenic attitude to wealth; one side of the schizophrenic attitude is that there’s plenty of wealth, but it’s just in the wrong place – too much spending by the rich, too much cash coursing through global financial markets and art markets. And then there’s not enough wealth – not enough spending on public services in an age marked by the austerity experienced by millions around the globe, too much debt loaded onto individuals and too much borrowing by states. These are the common reference points for what is usually the critique of neoliberal economics – of the one percent feathering their beds at everyone else’s expense, the cash flowing all one way.

And yet the glut of cash we see everywhere (except in our own payslips) and the glut of debt we see everywhere else is really only the financial consequence of the fact that the growth of real wealth – the production of stuff that millions of people need and want to live happy, comfortable lives – has ground to a halt. Economies in the West are barely growing, if at all, while businesses sit on cash piles they don’t want to invest to make more, better and cheaper stuff. Apple alone sits on a cash reserve of $206bn – a sum bigger than that held by some medium-size countries – yet doesn’t seem to know what to do with that money. But if one says that what we really need is more of everything, lots more of it, that everyone deserves higher living standards everywhere, more stuff and more leisure, in rich and poor economies alike, suddenly the conversation goes quiet. Suddenly, there’s too much wealth, too many people in the world, who all have too much stuff – we’re suffering from ‘stuffocation’, according to the latest antimaterialist lifecoaching bestseller, which wants us to switch from worrying about having ‘too many’ things to cherishing ‘experiences’. Search for ‘minimalism’ on Amazon and you’re as likely to find a self-help book on minimal, make-do-and-mend, learning-to-love-austerity lifestyle modification as you are a book on the boring American 1960s art movement; which emerged, ironically, at one of the highpoints of American prosperity.

There’s too much cash and not enough stuff, and we work too hard for it. And a truer critique of neoliberalism would be that the cash no longer knows where to go, so it pours into hedge funds, futures, commodities; into artworks, art foundations in gentrifying neighbourhoods, museums in the desert. Which is why I don’t care about what price someone paid for that Modigliani. It’s boring. It’s a sad sort of economics. Who cares? It’s a sign of desperation.

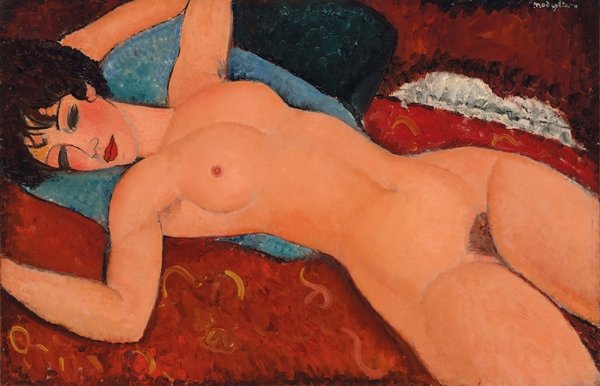

But what’s interesting to think about is what’s so interesting about Nu couché. All that blather cranked out by underpaid art historians – about its status in the history of modernist painting, its radical, even shocking take on the nude at the time it was painted, how few nudes Modigliani ever painted, and so on, which then gets converted into status markers of special quality – doesn’t actually mean, looking at it in 2015, that it’s any more or less enjoyable than a good bit of soft porn. And good soft porn is plentiful, and doesn’t cost $170m. Which is, of course, no use to the tidal wave of financial liquidity that doesn’t know where to go, and which would rather be absorbed in the ownership of a thing of extreme scarcity. So as I say, I could care less about what was paid for that painting. Criticism is a conversation, not about why something costs a lot of money, but why it’s good. And why everyone deserves more – lots more – of it. That is real value. The rest is just numbers.

This article was first published in the December 2015 issue.