Daido Moriyama’s Retrospective at C/O Berlin shows how the real world is scarier than photographs

Now eighty-four, Daido Moriyama has a good claim to being postwar Japan’s greatest photographer. It might, then, seem like a surprisingly cheapskate move on C/O Berlin’s part that many of the images included in his circa-250-work Retrospective aren’t photographic prints at all, but reproductions pasted to the walls. Still, given that the Osakan lensman founded his reputation via widely circulating, gritty photostories for Japanese photography magazines like Camera Mainichi during the mid-1960s, it makes formal sense. (His first major project, for Gendai no Me, in 1965: glimmering chiaroscuro images of preserved human foetuses in a former gynaecological hospital.) Inspired early on by William Klein’s hypercontrasty metropolitan reportage and by Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster silkscreens – see Moriyama’s fondness for photocopied images as well as his gravitation towards death scenes – he has always been a street-level observer, keen on obliterating layers of decorum or concealment to present modern-day Japan in its most insalubrious light.

Here, that’s established by the time we reach the second room, through a bevy of works from the series Accident: Premeditated or Not (1969) that Moriyama unfurled in monthly ‘chapters’ in Asahi Camera. Rephotographed media images of Robert F. Kennedy, whose ambiguous shooting inaugurated the series, are so murky and lossy that they question their own claim to any kind of truth. Trying to get past media obfuscation, Moriyama went on to accompany police officers on patrol around Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, but only saw minor incidents and so, fortuitously, came back with not much; a month or two later he repeatedly returned to the scene of a shipwreck, and he visited ‘ghost villages’ abandoned in the country’s rush towards industrialisation. A potentially upbeat exception in terms of subject matter, Zushi Beach near where Moriyama lived in Tokyo, begets a dank image of figures sardined together on what the artist, referencing high levels of pollution, called ‘a sea equivalent to a sewer’. What’s there instead of detail, in many of these grainy, near abstract yet muscular images, is a depressive sense of slow-motion omnidirectional catastrophe that can barely be grappled with or pictured.

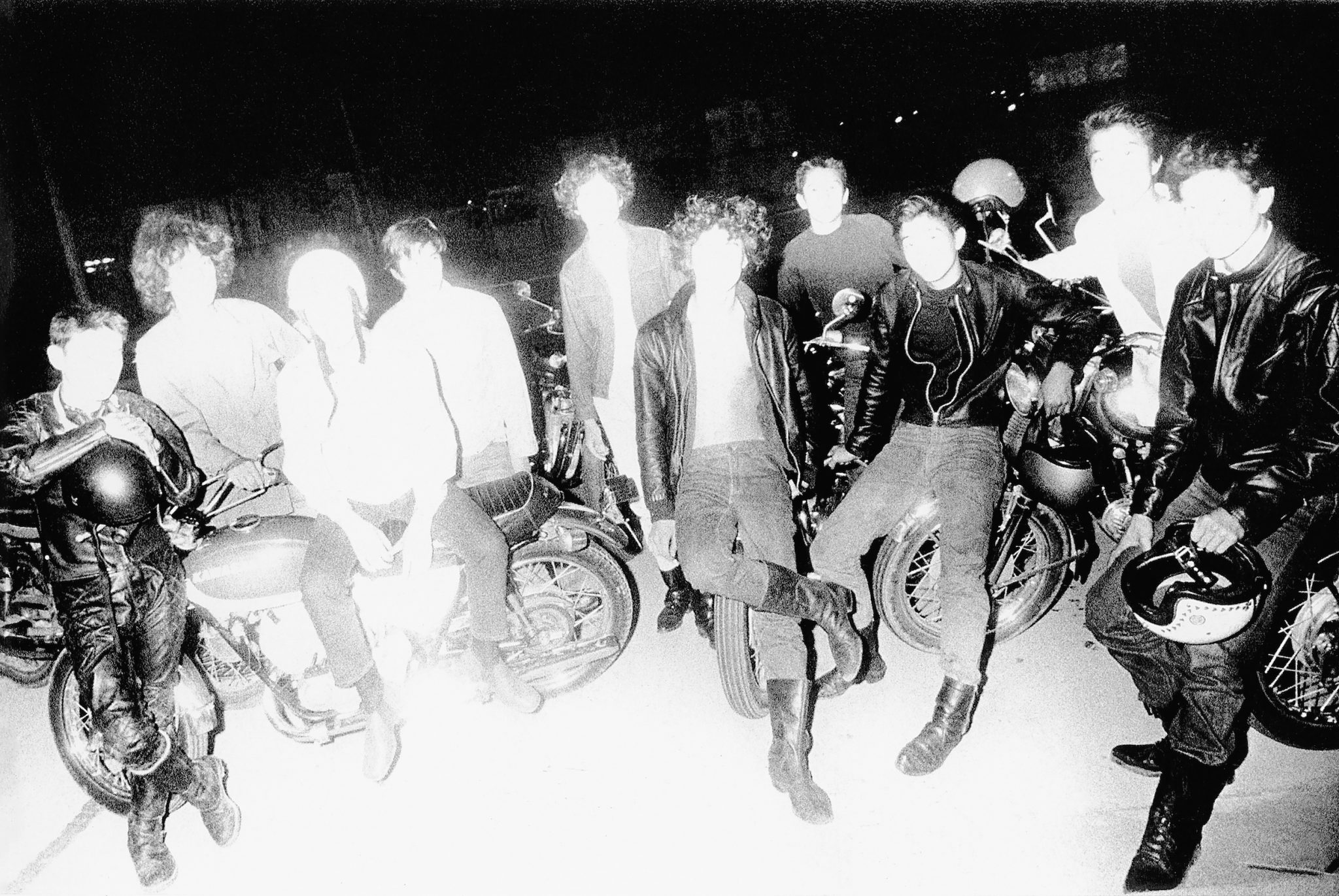

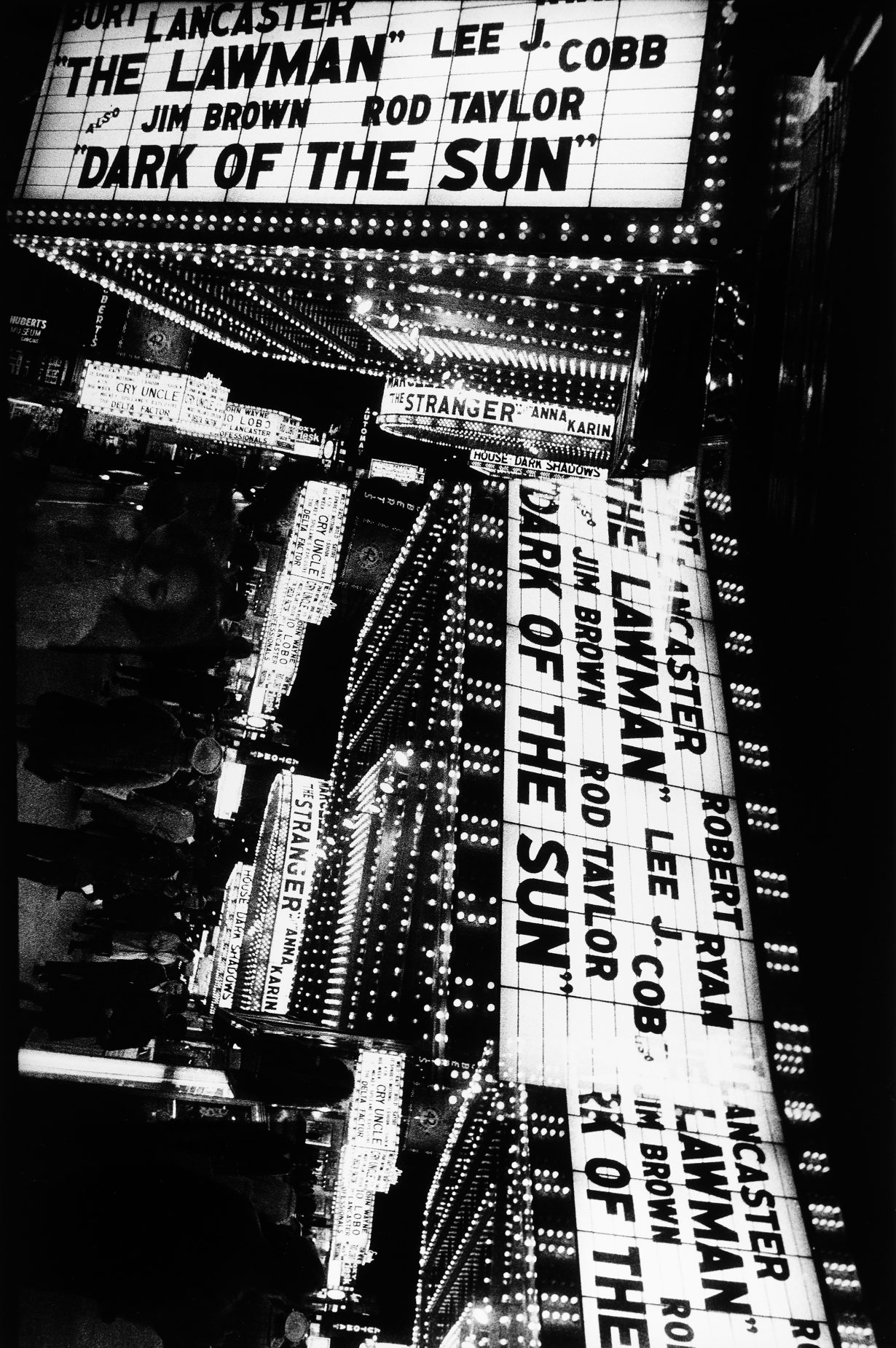

Evidently restless by nature, Moriyama next hit the road for several years, inspired by Jack Kerouac and the disconnected narrative episodes that constitute On the Road (1957). Across Japan, he established a variable poetics of threat: he photographed biker gangs, bears, rain-smeared windshields, soldiers, terrifying rows of strungup cephalopods – the show, though, mostly steers away from this. After going to America itself during the early 1970s and photographing, like Klein, directly on the sidewalks – a body of work that feels a bit of an indulgence and to be in the American photographer’s shadow – Moriyama said a premature goodbye to his medium with 1972’s Farewell Photography, a breathtakingly incoherent book-length collage of scratched negatives and near-abstract leftovers that outwardly abandons all belief in photography having the ability to say anything worthwhile at all. The rest of his 1970s are a blur; he seems to have been beset by anxiety and, relatedly, to have developed a sleepingpill addiction. The last major work of his prime years is Memories of a Dog (1981–82), in which Moriyama returned to his childhood haunts, trying to repossess his past.

Since then, he’s attended to his legacy in bodies of work like Labyrinth (2012), which uses his old contact sheets to scramble chronology, and – especially in the ongoing series Cities (1980; but again passed over here) – reestablished himself as a city photographer, expanding his remit to places like São Paulo. Moriyama asserts that metropolises are inexhaustible to someone with a keen semiotic eye and the stomach for constant change, sometimes zooming in on one aspect of the urban texture in a way that hives off into another body of work. Pretty Woman (2017), for example, tots up instances of images of the titular subject – youthful and fulsome and distracting, both in reality and in reproduction – and while there’s the lineaments of a critique of seductive distraction in there somewhere, it smacks of old man’s art. No matter. Having reached this point, and admired the guy’s stamina, you can then return to the show’s early phases, wherein Moriyama repeatedly uses photography to demonstrate that photography can’t tell you much – that the real world is much scarier than can be wholly depicted – and thrills you as he does it.

Retrospective at C/O Berlin 13 May – 6 September