There’s been a surge in environmentally-focused exhibitions in the Thai capital

Slowly but steadily, the notion sustaining so much climate crisis apathy and deferral – that the environmental impacts of our actions are remote from their causes in space and time – is being eroded. I was reminded of this, once again, when Bangkok’s serpentine river, the Chao Phraya, burst its banks on a hazy Monday morning in early November. From my 16th-floor riverside apartment, I saw torrents of mud-brown water engulf the courtyard of the local Chinese temple, fill the carpark of the Buddhist temple next door, then gush down the narrow soi (side-street) that leads to it. The waters steadily rose and rose before peaking at 1.33m above mean sea level. Yet street life barely flinched. A barefoot security guard with his trousers rolled up blew his whistle and ushered cars into the nearby hospital. Kids splashed and swam. Such is the coping mechanism in the riverside communities of the Thai metropolis – an imperilled city predicted to be below the high-tide line by 2050, and where residents who emit more carbon and greenhouse gases than those in London and Milan now wake up to smog for months each year (that same morning the air quality was ‘unhealthy for sensitive groups’: Bangkok’s haze season has dove-tailed with a heavy monsoon season that brought flooding to 32 of the country’s 76 provinces).

As the direst warnings about Bangkok unfurl with disturbing precision, it is becoming clearer that the flawed ecology of its soi – the inequalities in housing, rampant construction, soot-spewing diesel trucks, double-bagged streetfood – is partially culpable. And it is also clear that there’s not much, beyond cutting down on single-use plastics, leaving the car at home and crying foul, that the public themselves can do about it. Judging by the outrage on social media – They lied! Nothing changes! Empty promises! – stoicism in the face of the rise in extreme weather events and chronic pollution is here bound up with frustration at the lack of remedial measures and forward-thinking policy. Yet this nagging sense of precariousness and powerlessness is not unique to climate change; it also permeates commonly felt concerns about urbanism and the built environment (the recent razing of the city’s last standalone cinema, the tropical art-deco Scala, for example), as well as wider ideological misgivings about how justice and power in Thailand operate.

If there’s an upside to all this, it’s subtle: environmental (and social) degradation has triggered a groundswell in impassioned public responses. Bangkok does not have a long-range flood mitigation or clean air policy, but it does, for example, have catharsis through satire: a few hours after the flood, thousands were laughing about it thanks to Uninspired by Current Events, a Facebook page offering cartoon illustrations – some cryptic, others pointed – about Thailand’s ugly truths.

While Bangkok has not seen anything with the scale of Chiang Mai’s anti-air-pollution extravaganza Art For Air, nor the utopian or speculative ambitions of Rirkrit Tiravanija and Kamin Lertchaiprasert’s Land Foundation, exhibitions that broach the environment are also abundant. A retrospective of late Thai modernist Damrong Wong-Uparaj at the Bangkok Art Culture Centre was dominated by his idealised and sentimental depictions of simple agrarian life, while twee illustrations or paintings that pit man against wilderness and fetishise Nature have filled many a commercial gallery of late. More fruitfully, Warin Lab Contemporary, a gallery housed in the former residence of late wildlife conservationist Dr Boonsong Lekagul, launched in January with a year of environment-themed exhibitions.

Other exhibitions wear their ‘environmentalism’ more lightly. In The Ecological Thought (2010), Timothy Morton argues that a more honest and interconnected ecological art – an art that thinks beyond Nature, global warming, recycling or solar power, and includes ‘negativity and irony, ugliness and horror’ – has a distinct role to play in the climate crisis. ‘Art’s ambiguous, vague qualities will help us think things that remain difficult to put into words… art can allow us to glimpse beings that exist beyond or between our normal categories,’ he writes.

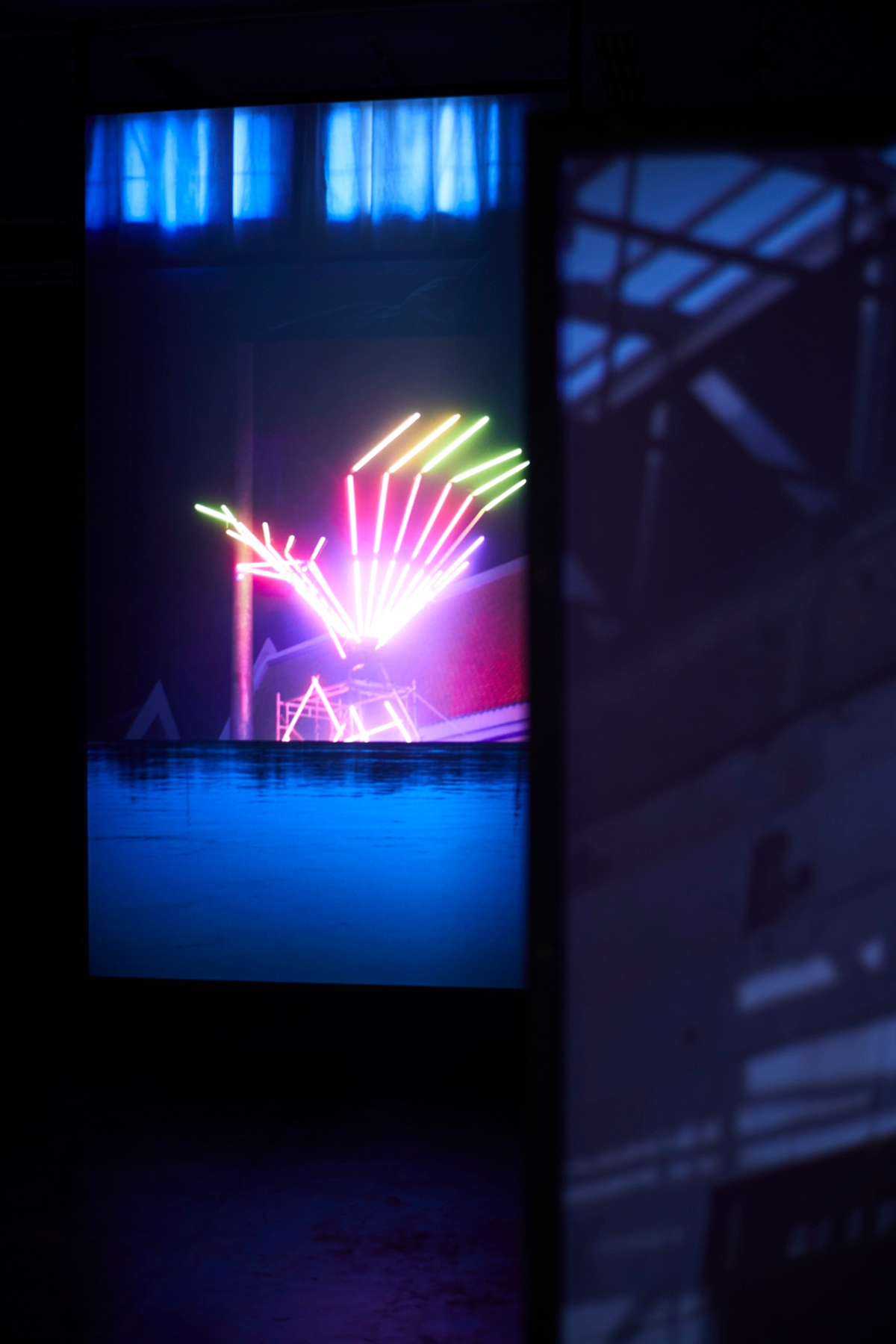

The multidisciplinary practice of, among others, Piyarat Piyapongwiwat occupies this liminal zone, as does Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s A Minor History, an ongoing two-part show at 100 Tonson Foundation that continues his decade-long study of the Mekong River, the silty brown waters of which are, due to silt-trapping dam projects funded by foreign investment, turning blue in places. Invoking both real-life extrajudicial killings and the mythical Naga serpent of northeastern folklore, A Minor History’s three-channel installation mediates northeast Thailand’s changing environment – the death of myths, activists, innocence, fragile ecosystems, ways of life – in a playful manner that defies rigid conceptual categories. Ecology is wildly layered with cosmology, politics, poetics.

That sinking feeling isn’t going away: Thailand’s lack of commitment was plain to see at COP26 in Glasgow, where it refused to sign new methane pledges and forest preservation treaties, or commit to phasing out coal power. But in Bangkok galleries, as well as besieged Bangkok streets, the ‘dark ecology’ Morton has articulated lives and breathes: ‘Things will get worse before they get better, if at all. We must create frameworks for coping with a catastrophe that, from the evidence of the hysterical announcements of its imminent arrival, has already occurred.’

From the December 2021 issue of ArtReview