“Too many loonies” drawled the careworn veteran art critic to ArtReview, as he quaffed his Bellini and gazed out towards the battlements of the Arsenale. ArtReview of course prefers the term ‘persons of challenged reality’ to ‘loonies’, but it could see the venerable ancient’s point: curator Massimiliano Gioni’s sprawling exhibition The Encyclopedic Palace lays on art by ‘outsider’ artists with a trowel, in order to suggest that art isn’t just a product of the ‘artworld’, but is a more fundamental human drive for knowledge and discovery, which often drives artists to eccentric and delusional extremes.

Now, ArtReview doesn’t always buy the whole outsider art thing, given that it’s often manifested in works on paper with every inch filled with intricate and laboriously obsessive doodles whose meaning is only really accessible to the outsider artist themselves, and ArtReview suffers from ADHD. But attention deficit is itself a sort of underlying theme of Gioni’s show, in as much as The Encyclopedic Palace – referring to a project by an obscure Italian-American for a skyscraper that would house all of humanity’s creative achievements – points to a sense of contemporary excess and overload, and our apparently increasingly futile attempt to make sense of everything. Cue a lot of forgotten historical art and the now-obligatory nod to ethnographic modes of curating, and The Encyclopedic Palace’s doors creaked open. So, primed for maximum delirium, ArtReview left the ancient scribe to his fifth Bellini, and plunged into the labyrinth of Gioni’s sprawling wunderkammer. Here’s a few highlights of what it found…

Chock-a-block

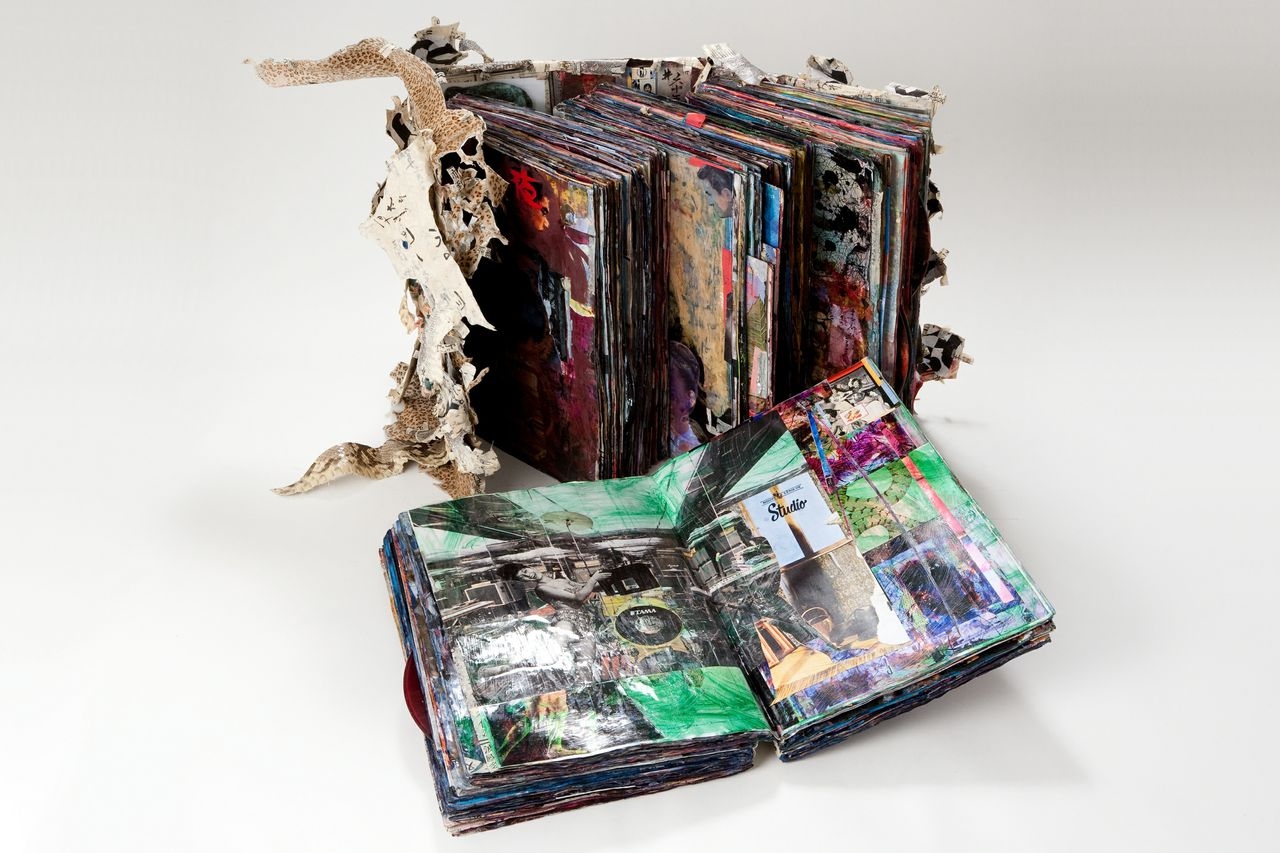

Out of all the meticulous displays of borderline-crazy visual obsession on show, ArtReview lingered on the jammed-to-their-covers Scrapbooks of Japanese artist Shinro Ohtake. A roomful of glass display cases presented over thirty years of Ohtake’s relentless pasting-in and decorating of ephemeral stuff – bus tickets, photographs, old pornography, receipts, food packaging – that most of us would just throw away. Exuberant accumulations of the flotsam of everyday life, piled-on with a kind of dispassionate carelessness that celebrates but doesn’t fetishise its material – Ohtake’s Scrapbooks make consumer overload something to revel in.

Girl Talk

There’s a lot of steamy eroticism in this show, ArtReview noted; from Hans Bellmer’s creepily fleshy drawings of perverse and mutant entanglements, through Soviet-era Russian Evgenij Kozlov’s adolescent erotic fantasies of what he’d get up to with his female neighbours, to the self-gratifying transvestisism of photographer Pierre Molinier; but American eccentric Morton Bartlett’s dolls – pubescent girls in exquisitely tailored outfits which the wall text insisted were ‘anatomically correct’ (ArtReview didn’t feel inclined to break the glass cases to check) – have all the precise strangeness of a true product of a lifelong private desire. Somehow charming and creepy, Bartlett’s dolls played on the other side of a line that makes outsiders of all who cross it.

Frank Talk

A lot of sex and eroticism, but most of it by men, harrumphed ArtReview, noting that maybe only a quarter of the show’s roster were women. So American Sharon Hayes’s deft social documentary video Ricerche: Three, in which she interviews various groups of ordinary Americans about their attitudes to sexuality, was a refreshing step out of all the cloistered obsessions of weirdo guys, into the more plural, tolerant, and yet perhaps even more complicated politics of sex in the twenty-first century. Intimate, yet never really a private matter, sex in Hayes’s video is shown to be a matter of social identity as much as personal preference.

Dig the Digital

No show about the contemporary condition would be complete without High Definition musings on how everything digital and ‘internet-y’ is making the real unreal, turning matter virtual, obliterating individuality or turning knowledge into a great big Wikipedia stew of info-babble. So while visitors could get hooked on Silver Lion winner (for a promising young artist in the International Exhibition) Camille Henrot’s dizzyingly edited digital ramble through the various narratives of the world’s origin and history, or Mark Leckey’s oracular, multi-media meditation on the soon-to-dissolve distinction between inanimate objects and an image-world full of animate things, ArtReview found itself pondering German Hito Steyerl’s quirky and amusing video on pixel resolution and the political act of disappearing or being ‘disappeared’. It takes a lot to get from a USAF camera calibration pattern in the Mojave desert to the Three Degrees singing When Will I see You Again, but Steyerl made it all crystal-clear, sort of.

Alter Boy

All this talk of virtualisation was making ArtReview yearn for something more tangible, at which point it trudged distractedly into the pile of fine grey dust that someone had scattered across the gallery floor, only to be told that this was in fact British artist Roger Hiorns’s ‘atomised’ marble church altar. Surrounded by the abstract-spiritual paintings of Hilma Af Klint, Hiorns’s pulverised piece of sacred architecture seemed to mock much of the spiritualist ramblings that dotted the exhibition – from Rudolf Steiner’s ‘anthroposophical’ blackboard diagrams to Aleister Crowley’s occult reimagining of the tarot deck – while also calling into question the failing rationality of modern-day secularism…