So Art Basel is over for another year, with a flurry of press releases about ‘strong sales’, ‘record footfall’ and a welcome return of something called the ‘serious collector’. But for all the self-congratulation, this writer is always a little nonplussed by the experience of this extraordinary event, with its 300 galleries inhabiting two vast floors; with ‘Unlimited’, its gargantuan curated exhibition; and with its collateral programme of talks and its subsection of younger galleries, ‘Statements’ (these last three hived off, a little forlornly, to the newly renovated Hall 1, away from the main fair stands).

There is more art than one could ever look at here, but for all the talk of strong sales, buying is only half the point. Basel is a place to meet and catch up with contacts, see what galleries are up to and hear gossip about artists and other artworlders, with the art as a sort of ever-changing colourful backdrop. And the thing is, much of the art on display isn’t there just to be looked at for its own sake. That may sound strange, admittedly. But ultimately, many of the artworks in an event such as Art Basel often exist as placeholders, stand-ins or symbols for something else – namely an artist’s wider practice, status, reputation.

Which is why I find myself looking out for those works that aren’t just behaving as calling cards for their creators’ well-known artistic brands. These are usually on gallery stands that refuse to get too cluttered, that have confidence in the few pieces they have on show. So my first stop was at Jan Mot’s militantly colourless presentation of works, and in particular those of deceased, almost-forgotten French conceptualist Philippe Thomas, whose works – issued by his invented agency Readymades Belong to Everyone – forced the critique of authorship to breaking-point: buyers of Thomas’s works would ‘become’ the authors of the works they bought, Thomas renouncing any claim to intellectual rights over them. No wonder he disappeared (Thomas died in 1995), even if he haunts the memories of a current generation of critically minded artists.

But it doesn’t have to be fugitive postconceptualist art to float this critic’s boat – though works by Liam Gillick (a huge tabletop of reading matter referring back to a number of the artist’s earlier works, at Esther Schipper) and Art & Language (one of their Background, Incident, Foreground paintings, at Juana de Aizpuru) were a reminder that artists can be successfully awkward about the system they inhabit. So the younger Alice Channer, at Approach, managed to do something strange and beguiling with an assembly of low curving stainless steel panels, on whose edges were balanced aluminium casts of truncated human fingers and meteoritelike rocks, while Shannon Ebner’s framed photoseries The Man in the White Hat Dropped It (2013), at Sadie Coles, forced you to figure out a complicated game between text, photograph and narrative: stuttering sentences, made out of cutout letters photographed propped against a wall, strung out a constantly shifting account of obscure people and places, in which the medium ultimately drowned out the message.

But now I’m distracted and I’ve gone off to chat with some curator about something or other, on the balcony overlooking the courtyard, the air thick with the smell of grilled Swiss cheese. Maybe it’s just that subdued, enigmatic works win out in the attention-seeking, slightly hysterical environs of the art fair. Strolling through the enormous exhibition hall that houses Unlimited, dotted with enormous sculptures that seemed to have been tipped out of a cargo jet, this was definitely the case. There’s a fun-fair aesthetic that has firmly taken hold of the Unlimited space. Roll up! Walk under Piotr Uklański’s huge dangling textile uvula, Open Wide (2012)! Clamber into Atelier Van Lieshout’s slightly stinky survivalist fibreglass habitation Hagioscoop (2012)! Try not to go blind looking into He An’s floodlit metal tube Hubble (2013)!

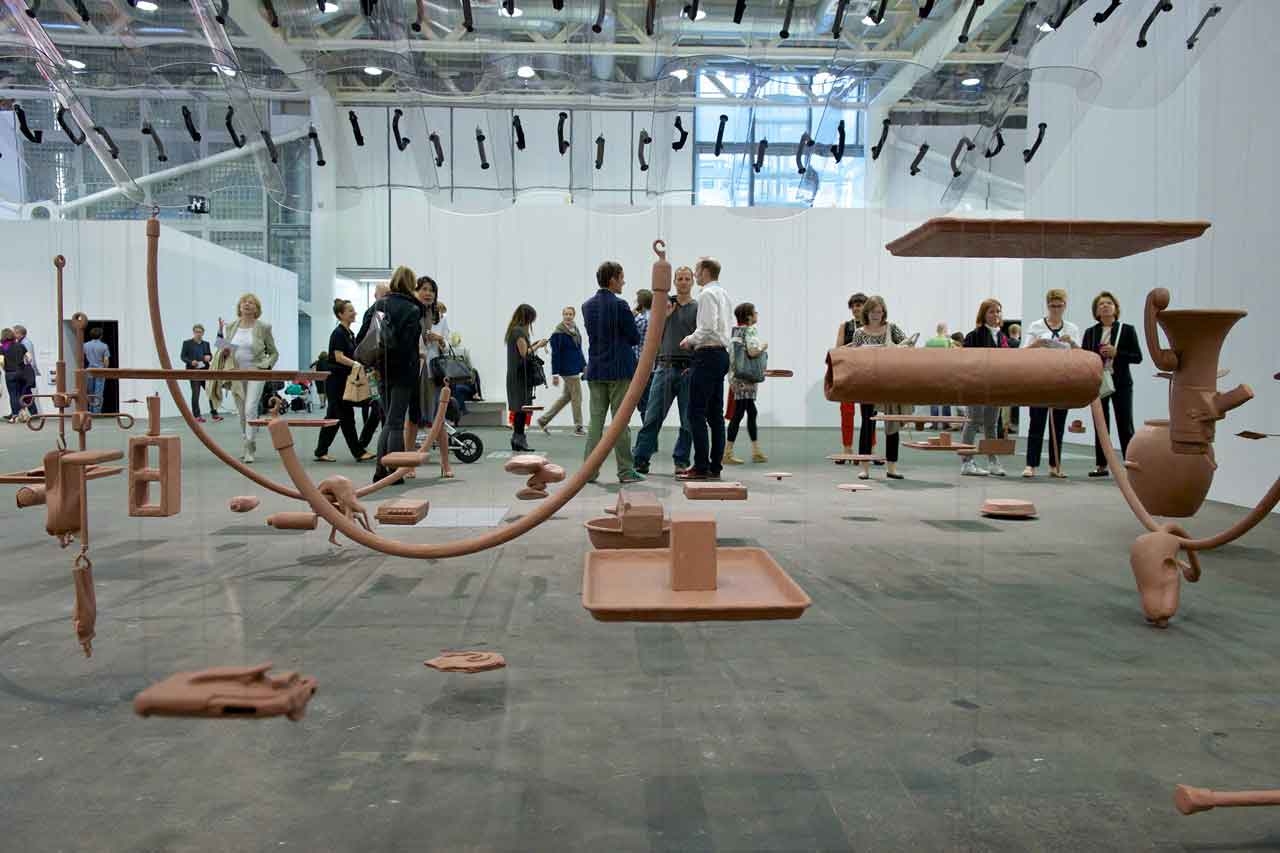

Still, such daffy rides could be ignored for long enough to enjoy Michael Joo’s poised and solemn hanging sculpture Indivisible (2012), with its shimmering canopy of transparent riot shields hovering over a cloud of suspended domestic objects and ailing animal forms, all rendered in clay-brown plasticine. And while no one seemed to be able to work out where François Curlet’s haggard undertaker was going in a black, hearse-converted E-Type Jaguar, in his film installation Speed Limit, (2013), endlessly looking for the right road in a wet landscape of dank cabbage fields (was it Belgium?), having clearly borrowed the car from 1971 black comedy movie Harold and Maude, the circular, Beckettian futility of Curlet’s video was, somehow, uplifting.

Seriousness can be a quality in short supply at Art Basel. And sometimes you find it in the funniest places.