Black Box at Ames Yavuz Gallery, Singapore probes a growing cynicism towards China’s authoritarian regime

In Yang Xiao’s video Goodbye Language (2023), the artist has filmed rare – and, in the Chinese mainland, probably banned – footage of Chinese officials in protective suits walking through the empty streets of Shanghai during the city’s lockdown in 2022, when the Chinese government was stubbornly pursuing its zero-COVID-19 policy, even while other countries were opening up. Slogans blare in Mandarin through the neighbourhoods: ‘Strictly implement new progress functions, be cohesive and adhere to core consciousness, demonstrate focus on aligning awareness…’, and so on, nonsensically. The propagandistic, Newspeak-ish text was generated by an AI programme with words inputted by Yang, which he then played on a speaker from his apartment window.

Empty bureaucratese is not new to the Chinese and cynicism towards China’s authoritarian regime informs this important and fascinating exhibition of work by 12 Chinese artists that was mostly created during the pandemic. Due to the nature of the content most of it would be impossible to show at home. The show is a record of the psychological and physical toll of living through the pandemic and how it intensified a longstanding mood of distrust of and disappointment with those in power. This jadedness can be traced back to the post-Tiananmen, 1990s avant-garde art movement described as ‘cynical realism’ and those artists disillusioned by Deng Xiaoping’s promises of modernisation and liberalisation. Now, the CCP, with even more sophisticated organs of control and discipline, disappoints a new generation of artists. But while Black Box is bleak, it is also funny, cruel, sad, sweet and defiant. It looks at power and its abuses unflinchingly, while acknowledging our yearning for pleasure and connection.

In fact, the more brutal the abuse, the more beautiful is the work. In Tong Tianqing’s large, mural-sized ink painting Wrest (2022), two greyhounds fight over a rabbit, recalling a bloodsport that was popular during the pandemic in the outskirts of Beijing. Its graceful lines, with the greyhounds’ bodies and tails joined together to form the shape of a heart, only brings the sadism into greater relief. Meanwhile, Wu Chen’s Gold, Flies, Gems, Bowling Ball (2024) depicts a symbol of power – a crown – in gilded vulgarity. Painted in the flat, stylised graphic style of a crest or insignia, it is studded with jewels, skulls, houseflies and disembodied female legs, parted to expose the genitals.

Some works evoke profound grief and pain. Liu Sheng’s incredible painting Noon Haze (2024) portrays a funerary custom in rural Guangdong, where after a death, village women would cut up a and share a pig among different families. A woman holding a pig’s head, her mouth open in lamentation, looks to the sky. The rest of the carcass is splayed on the ground atop a flattened cardboard box. A row of women, presumably mourners, sit on yellow stools with their hands on their laps. The scene has the frozen, overbright quality of an overexposed photo – the background is nearly white and the human figures appear to be floating – and the unreality of a waking nightmare, in which roles and meanings are slippery: the animal body stands in for the human corpse, while the shadowed faces of the mourners suggest other malevolent entities.

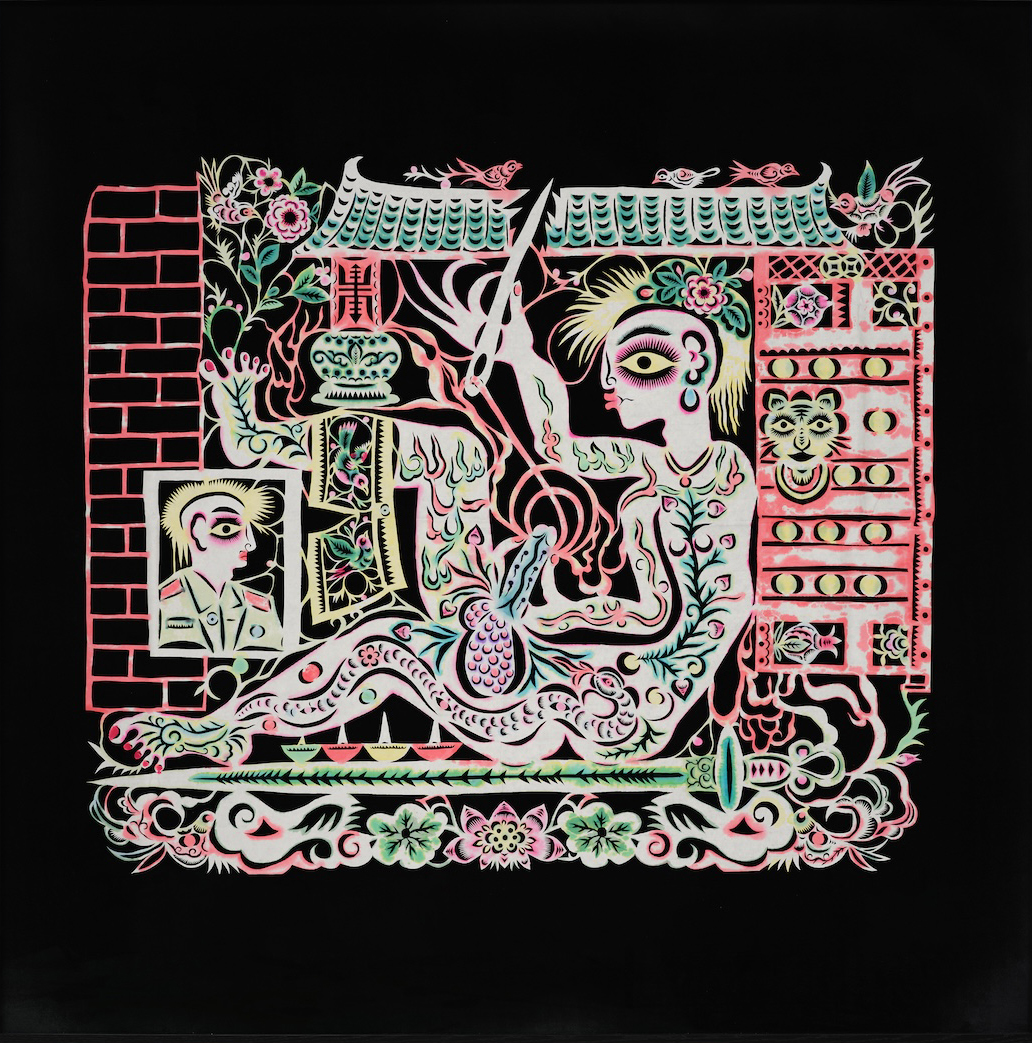

But human expression finds a way in the most restricted of circumstances. Hu Jiayi‘s video Boxing (2020) shows the artist dancing in an abandoned shopping mall with boxing gloves on her hands and feet. Punching the ground on all fours convulsively, and scuttling up and down stationary escalators, her movements strain between frustration and freedom. Executed in the style of extravagantly filigreed traditional Chinese paper cuttings, Xiyadie’s elaborate paper cutouts express queer desire in a society where homosexuality is decriminalised but gay communities are still persecuted. Sewn (1999) is a self-portrait of the artist reclining in a house with his pants down, gazing at his male lover, while stitching the tip of his penis with needle and thread. The needle also pierces the ceiling of the house – a motif expressing a longing to break through the structures of social orthodoxy.

The most moving work suggests that despite periods of isolation, we find ways to communicate. Jiang Zhi’s video Name (Aranya), (2024) is filmed in Aranya, an exclusive beach resort area in northeast China, that is empty of people in winter. Actors are seen in deserted brutalist concrete buildings, green hills and a beach. One by one, they hold a leaf to their lips and blow out a long thin note into the wind. China’s early COVID-19 whistleblowers, who have died or been jailed, come to mind. Melancholic as it is, this can also be read as a work expressing hope and resistance in a society where information is highly controlled, and celebrating ingenious systems of codes, signals and messages – whether expressed online, on the streets or in art – that show solidarity and support.

Black Box at Ames Yavuz Gallery, Singapore, 29 August – 19 October

From the Winter 2024 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.