In Nurture Gaia, the glamour of the global overrides the lure of the local

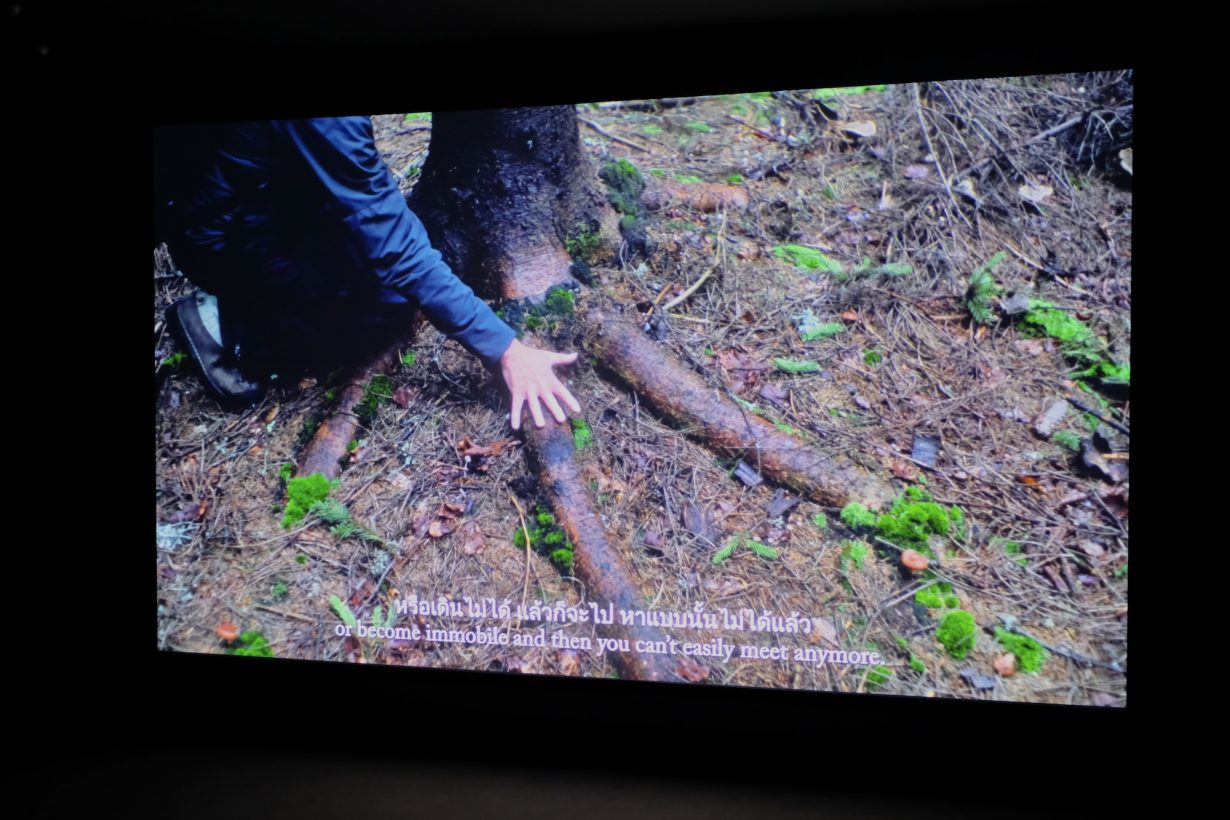

Sprinkled through the fourth Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB) are works that animate its title and theme in intriguing ways. The roving lifeforces of Lisa Reihana’s video Groundloop (2022), for instance, sit neatly with the curatorial statement’s invocation of James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis: the Indigenous peoples of Oceania, dressed in futuristic costumes inspired by the wood-stick charts of the Marshall Islands, sparsely populate self-regulating lands linked by an unbroken Pacific Ocean corridor, through which ancestral spirits and forms of wisdom journey. Also gently prodding us to think anew about our position and agency within the narrow band of earth and atmosphere that supports life – the ‘critical zone’ central to the political ecology of philosopher Bruno Latour, who is also invoked – is the uncanny lyricism of Rob Crosse’s Wood for the Trees (2023), which juxtaposes footage and audio from contrasting habitats: an old-growth forest and an LGBTQ+ housing project in Berlin. And David Shongo and Filip Van Dingenen’s Suskewiet Visions (2022) – an attempt to document, using wooden tally sticks and a willing public, the singing of male finches in Southwest Flanders – is yet another community-oriented offering that seems, obliquely, to argue for greater environmental awareness, or action, at the local level.

After digesting these works (and the references to Greek mythology, nature’s defilement and Mother Earth), an unsuspecting visitor might reasonably hope, or surmise, that the organisers of this corporate-funded, citywide event have been proactive when it comes to planetary care: that efforts to make BAB part of the climate solution, rather than the problem, have been put in place on the ground. No such luck. Nurture Gaia is a business-as-usual biennale in which the glamour of the global overrides the lure of the local, and where opening week was timed to coincide with the launch of One Bangkok, a vast, gridlock-exacerbating mixed-use development built by the sponsor’s sister company. Permanent sculptures in its central square – Tony Cragg’s It is, it isn’t (2023–04, 35 tons of gleaming stainless-steel that calls to mind towering rock-formations and the liquid-metal effects of James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgement Day, 1991), and Anish Kapoor’s S-Curve (a glorified fairground mirror, 2006) – are BAB artworks overshadowed by the highrise setting. Around them, on LED screens, a Nurture Gaia video-promo alternates with ads for the new ‘Heart of Bangkok’ and its onslaught of high-end shops and restaurants. While ‘sustainability’ is a One Bangkok buzzword, the only things being nurtured here, seemingly, are corporate art collections, consumerist appetites and bottom lines.

A glance at the sponsor ThaiBev’s Sustainability Report 2023 spells out the kind of nurturing that BAB itself, with its 240-plus artworks by 76 artists, is really interested in: ‘ThaiBev is committed to elevating Thailand’s contemporary art scene to international parity and creating economic stimulation,’ it states. The natural inference to make, in light of this edition’s mutterings about humanity’s ‘lack of respect’ for Gaia and quoting of United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres (‘surging temperatures demand a surge in action’) is that BAB’s backers have reasoned that these cultural benefits offset Nurture Gaia’s environmental footprint (which, ironically, given ThaiBev’s net-zero greenhouse-gas targets, as well as the biennale’s theme, is glossed over). And exploring the 11 venues, you may well conclude they’re onto something: BAB is certainly contributing to the common (albeit human-centred) good.

Its popular appeal is most plainly apparent at the BACC, where visitors lured by the promise of striking portraits or selfies soon find their mental faculties (and photo skills) being tested by quieter, more opaque works, from research-led projects to endurance art. After heading up to the top floor to snap Choi Jeong Hwa’s giant inflatable fruit and veg (a big hit), they eventually slink off to glance at Yanawit Kunchaethong’s moving material-led reflection on the industrialisation of his father’s rural land in Thailand’s Phetchaburi province. Not far from his organic prints and repeating concrete verse (spelled in wood dust across the floor) sit the remnants of Moe Satt’s performance, for which the political exile spent hours in a crouched position while passersby scrawled hopeful messages about war-torn Myanmar on a T-shirt stretched over his head, and Adel Abdessemed’s 19-second loop of a Charolais bull pacing back and forth in the artist’s studio.

Most of the show is as meandering as this brief sketch suggests. To the extent that it quickly becomes clear that the exhibition’s curatorial team (artistic director Apinan Poshyananda alongside Brian Curtin, Pojai Akratanakul, Akiko Miki and Paramaporn Sirikulchayanont) have pulled into its orbit almost every subject under the sun, not just works of an ecologically minded nature. Amid this hotchpotch, Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2013) – a video critique of ‘the universalist ambition to represent the totality of the world’, as the wall text puts it – comes off like a 13-minute distillation of, or commentary upon, the show at large. Both enlist dissimilar practices and mediums, and both toss references to mythology and science about with abandon.

All of which makes those patches where things do gel more rewarding. Amid the Italianate-style architecture of the National Gallery of Thailand, works by a mainly Southeast Asian cohort benefit from the spacious rooms and unfussy curating: Lêna Bùi’s chromatic ink-and-watercolour-on-silk paintings, for example, which hover between depicting the elements and abstraction, seem to commune on a deep formal and spiritual level with Supawich Weesapen’s blazing, rusty orange landscape and starscape paintings. Cole Lu’s site-specific intervention amid the polished wood and Buddhist novice manuals of the library at Wat Bowon temple – two wooden gateways depicting, through expressive pyrography, scenes related to the cycle of birth and death – is a reminder that the BAB is at its best when it leans into its locations (The Engineers, 2024).

In Bangkok’s old town, we also find the local heritage lens that Poshyananda has used in past exhibitions being dusted off. As with 2012’s Thai Transience, works by Thai artists (predominantly) at the National Museum Bangkok – another new venue – are placed alongside ancient artefacts. In one instance, Dusadee Huntrakul’s bronze hands, outré pottery, ceramic seashells and pencil drawings of UFO sightings, as well as sketches by his son, are arranged in vitrines alongside animal fossils, bone fragments, a stone torso, prehistoric Ban Chiang bracelets and Khmer lingams (A Verse for Nights, 2024). The role of the hand in shaping tools, stories and all human history cannot be overstated, he playfully suggests.

A collaboration with the country’s Fine Arts Department, this mixing of the classical and the contemporary provokes a new set of questions and quibbles – some of the other seven dialogues feel forced (among these the pairing of Joseph Beuys drawings and sculptures with Dvaravati earthenware), while Nurture Gaia’s rhetorical privileging of Greek mythology seems counterintuitive in light of this imposing showcase of the Thai equivalent (including an accordion manuscript gruesomely depicting the Tribhumi, or Three Worlds, of Theravada Buddhist cosmology). Yet this move is also, perhaps, a tacit acknowledgement that the wider format could, in terms of how Thai and Southeast Asian artworks are presented, benefit from a shakeup. Or nurturing. In this respect, a 2014 warning by art scholar Astri Wright (given in the paper ‘The Arc of My Field is a Rainbow with an Expanding Twist and All Kinds of Creatures Dancing’) about a looming crisis for the region’s art historians (Poshyananda among them) resonates with much of the show: ‘The danger as far as I can see is that the local will disappear in a mishmash of global perspectives where once again the European(-derived) ones remain dominant.’

Bangkok Art Biennale 2024: Nurture Gaia, Various venues, Bangkok, through 25 February