Bailing out arts venues doesn’t really amount to much if those venues can never really reopen

Among the biggest casualties of lockdown is the type of public life that happens indoors. In that respect, the world of the arts has been among the hardest hit. In the UK, while museums, public and commercial galleries have tentatively reopened, the economic crisis engulfing live performance venues – concert halls and theatres – is so serious that some were, by the end of June, preparing for imminent closure. On 5 July, in response to a growing outcry from arts organisations, the UK government announced £1.57 billion of emergency grants and loans for ‘Britain’s museums, galleries, theatres, independent cinemas, heritage sites and music venues’. The money was met with trills of appreciation by the arts sector, with Arts Council Chairman Nicolas Serota going so far as to declare – rather oddly adopting the Boris Johnson-like tone of a wartime leader rallying his loyal followers – that ‘our amazing artists and creative organisations will repay the faith that the government has shown by demonstrating the range of their creativity, by serving their communities and by helping the nation recover as we emerge from the pandemic’.

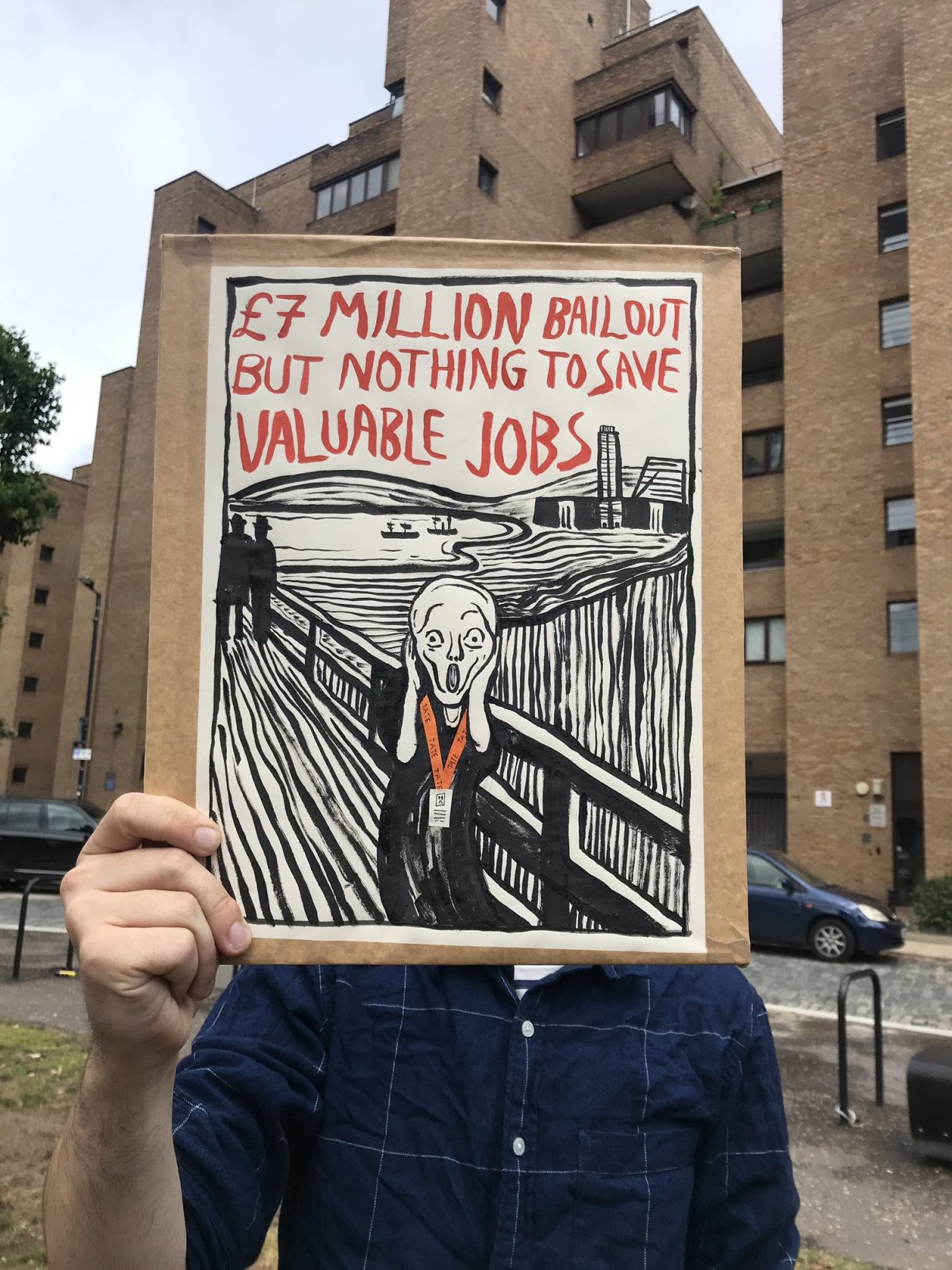

Since then, many have started to question what all this bailout money is good for, and whether it will in any way benefit the thousands of artists and performers who have suddenly become unemployed because of shuttered venues. Writing in The Guardian, freelance theatre director Fiona Laird criticises how ‘many subsidised theatres also employ large numbers of administrative staff’, a ‘growing cohort of administrators’ with ‘all the perks of holiday, sick pay, maternity leave and workplace pensions that full-time employment affords’, while ‘creatives are immediately unemployed the day after a show closes’. ‘The bailout money’, Laird scathingly concludes, ‘will in all likelihood go to the Arts Council, which will then distribute it to the institutions it has been funding for years, which will in turn probably spend it on retaining as many of their full-time (non-creative) employees as possible.’ In The Telegraph, opera star Allan Clayton similarly noted that, while he was happy for ‘the institutions, and for friends and colleagues who are employed by them… I’m still deeply concerned, because hundreds of thousands of freelancers like me… won’t see any of that money.’ Meanwhile the Design and Artists Copyright Society, on its ‘Fair Share for Artists’ campaign website (a campaign originally started to advocate for artist resale rights, and supported by a number of visual arts organisations, among them the South London Gallery, Birmingham’s IKON Gallery, and the New Art Gallery Walsall) reacted critically to the government announcement: ‘Visual artists’ livelihoods were destroyed the moment we went into lockdown,’ it declared, ‘and there is no sign of improvement. Most artists do not qualify for government support, and we fear that this announcement will mean nothing to the thousands of artists who cannot pay for materials, face eviction from studios, who have seen work cancelled, opportunities dry up, and sales plummet.’

What the government’s bailout has managed to highlight is two mutually destructive aspects of how the subsidised arts sector has evolved in recent decades: firstly that in the creative arts, artists and performers are mostly still part of the ‘gig economy’; and secondly, that even supposedly publicly funded arts venues are now heavily reliant on commercial income – from cafes, retail, membership schemes and tourists – and have been happy to use low-paid and casual labour for many of their ancillary services, while ending up with large permanent administrative staff. Not surprisingly, as soon as the bailout was announced, many casualised workers at big subsidised arts venues were calling it out: members of the Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS) at Tate are currently being balloted for strike action, in the wake of Tate Enterprises’s announcement of 200 redundancies across Tate’s sites. Similar redundancies have been announced at the South Bank Centre and the National Gallery. The intertwined relationship of artists’ precarity and general precarity in the wider gig-economy workforce is underlined in a tweet by the PCS Culture Group; ‘We are artists, writers, photographers, dancers & musicians. Life & soul of @Tate & every visitor’s helper’.

What the pandemic has brought crashing home is that, while much is made of publicly funded arts, many arts organisations have become heavily dependent on self-generated commercial revenue, ‘public’ in name only. In 2018-19, Tate’s government grant constituted less than 30 percent of its income, for example, and the National Theatre’s grant from ACE now counts for only 16 percent of its revenue. These organisational and business models are the product of successive governments’ demand that, while the arts should serve ever-growing public-policy demands to do with access, education and inclusivity, they should also pay their own way, increasingly from private philanthropy and commercial income. In many ways, this model looks increasingly broken: while Tate’s commercial trading income amounted to £37.5m in 2018–19, its trading costs were £34.3m. On those kinds of margins, you might argue that the government could just write Tate a cheque for an extra £3m, and not worry so much about coffee stands and gift shops.

Or, maybe not. What the COVID-19 bailout really amounts to is a panicked response to the disastrous consequences of shutting down public life, culture and art; keeping the infrastructure bumping along (and keeping its permanent staff in jobs), while not really admitting the catastrophe which has overtaken those who have no real security of employment. But it also remains completely blind to the fact that, in reality, art and culture can’t be reduced to just what goes on in subsidised art venues; it’s the complicated, spontaneous, provisional ecology of self-started nonprofits, pop-ups, artist-run galleries and spaces, independent events, video-screening clubs, and indeed, bars, nightclubs and meeting spaces – in short, everything about the urban cultural world that isn’t gifted with public funds – which is faced with annihilation, not so much by COVID-19 itself, but by the rules which make pretty much any kind of gathering, exhibition (outside of commercial and public galleries) or event illegal, along with the now deeply entrenched sense of fear among many. The fear of contracting the virus ‘out there’ has morphed from a response to a serious outbreak into a pre-emptive reorganising of social life to prevent any re-emergence of the virus anywhere. That is the indefinite ‘new normal’ the arts now face.

Bailing out arts venues doesn’t really amount to much if those venues can never really reopen. While Boris Johnson has committed himself to returning the UK to ‘significant normality’ by November, and the government’s aspiration is to reopen indoor performances from 1 August, this is subject both to the stringent ‘COVID-19 secure’ guidelines and the unknown results of mysterious ‘pilot’ performances that are taking place ‘as soon as possible’. Such uncertainty, combined with the financial chaos wrought by the collapse in commercial income, may, and will actually amount to keeping organisations partially (or wholly) mothballed until that time when a vaccine is found, or COVID-19 somehow magically goes away. London’s Barbican, for example, has cancelled all planned autumn 2020 concerts though to December. Livestreamed concerts replace them.

Of course, while the chair of the Arts Council opines weirdly about artists ‘serving their community’, artists are organising themselves to make art happen despite COVID-19, whether legally or illegally, trying to scrape together a living, while actually serving art to those of us who desperately want it: actors are offering pop-up open-air Shakespeare, for example. A few weeks ago, along with 30 other people not in my ‘household group’, I found myself watching a theatrical adaptation of Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time, staged in an abandoned fitness centre. And if ‘high culture’ isn’t your thing, illegal raves have of course mushroomed.

It’s possible to mask-up and plod round a predetermined route through the National Gallery or Tate Modern. These are spaces full of objects that must stay visible, and it would be nihilistic to wish these places shut for good. But it’s basically impossible to ‘socially distance’ in a theatre or concert venue – not, that is, without decimating capacity and making events commercially impossible, and, of course, killing dead the point of civic culture – sociability, togetherness and collective appreciation. The biggest victim of all this will be informal, non-institutionalised, do-it-yourself culture.

To bail out arts organisations to stagger on for a few more months, without being honest about the fact that public gathering will remain illegal, without any acknowledgement that the semi-privatised model cannot return, and without any real desire to see these places of collective culture reopen, is a vast evasion of responsibility. In the meantime, millions are spent, but not on artists, and not on art.