What form will the artworld take as it (slowly) emerges from the age of the virus? In an age of uncertainty, the September issue of ArtReview provides answers

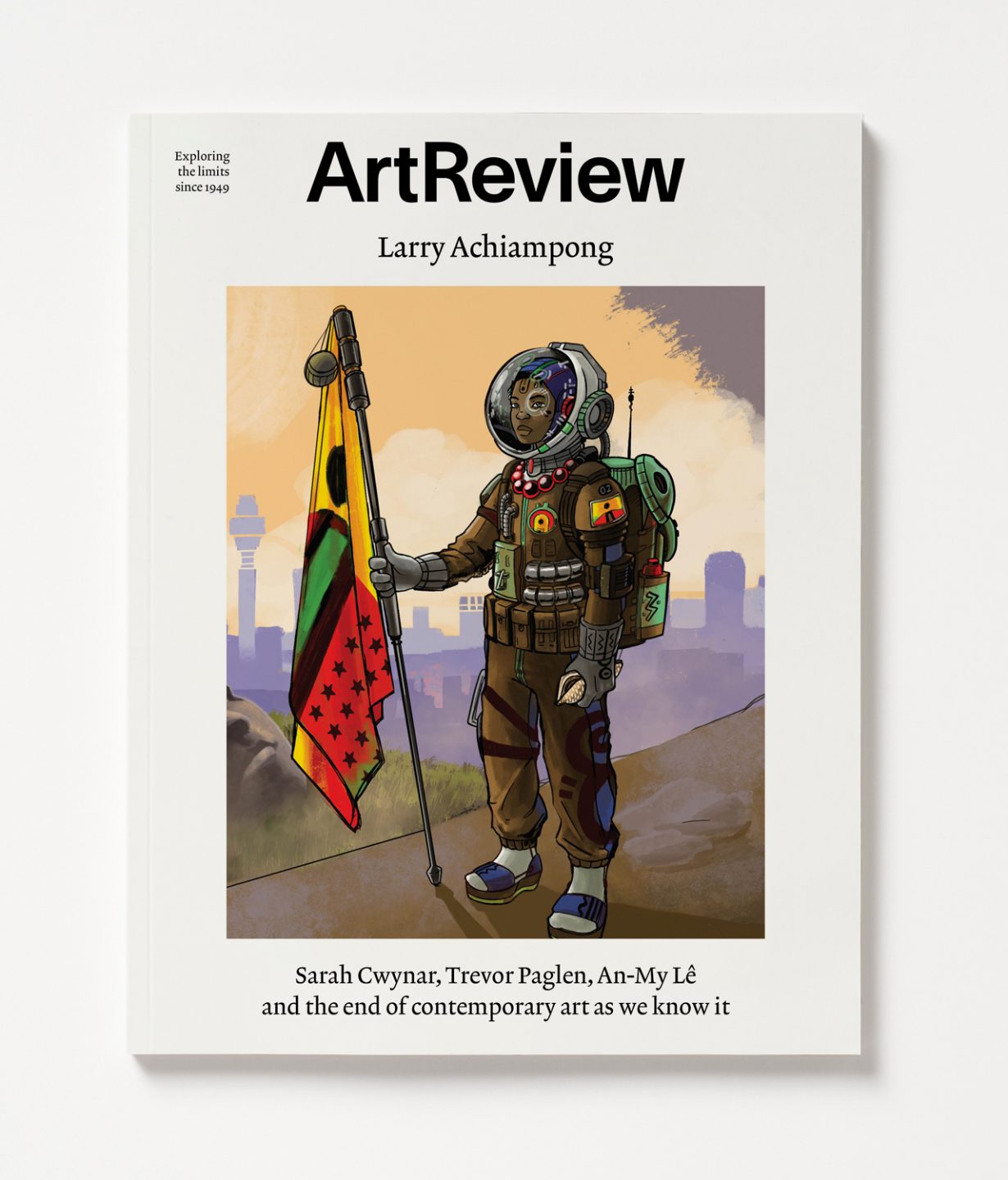

As issues of race and racism bubbled to the surface in Europe and the US, British-Ghanaian artist Larry Achiampong wrote a series of letters to his children celebrating their identity and ancestry – these texts, for an artwork to come, are presented in ArtReview for the first time. ‘I aim to treat the present with a consideration and dignity absent in the treatment of my ancestor’s narratives,’ he explains. Resistance is key to Achiampong’s work: told through the lens of Afrofuturism and Pan-Africanism, his series speaks of the hope for a better world, and of art’s unique ability to reshape the future.

Reflecting on his own lockdown experience, American artist Trevor Paglen says: ‘This time has been many, many things, but in terms of making art, it’s been a moment at which there’s been a huge change in the way that images mean things… there are such larger forces at play, determining the meaning of things: it feels like trying to swim in the middle of a giant storm, and all the waves are 50 feet high.’ In an exclusive preview of his new shows at Pace London and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, the artist explains how meaning is generated in a digital world.

In a written dialogue around the subject of crumbling ‘old’ infrastructures, J.J. Charlesworth and Liam Gillick dance on the ruins of a late capitalist artworld, assessing the effects of a sudden halt in institutional shows, art fairs and biennials on future routines. Meanwhile, Ben Eastham makes a case for adapting what the late critic and curator Germano Celant termed a ‘poor art’, for our times. ‘As we enter another period of social and economic crisis, in which the systems maintaining contemporary art’s value come under unsupportable strain, how might we reimagine how, to what and to whom we ascribe value?’ he writes.

During New York’s lockdown earlier this summer, photographer An-My Lê, experiencing PTSD triggered by childhood memories of the Vietnam War, found comfort in the messages of solidarity and hope written on the marquees of shuttered arthouse cinemas. Along the way, Lê unexpectedly found a visual syntax for supporting the Black Lives Movement. ‘Protest is a commitment to clarity, urgency and spontaneity. The slogans and chants only work if they can be shared and invested with belief… The language of protest and resistance demands a response.’

Also in the issue

Ross Simonini speaks with photographer, musician and filmmaker Farah Al Qasimi, whose works reflect on the intersections of American and Middle Eastern culture. Chris Fite-Wassilak takes the time to conduct a close analysis of Canadian artist Sara Cwynar’s Red Film (2018), while Martin Herbert analyses in highly personal terms the significance of Belgian artist Kris Martin’s Idiot (2005), a handwritten copy of Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot; architect Sam Jacob considers what museum galleries might look like and be used for if all the stolen objects and artefacts in these collections were returned to their countries of origin; and Patrick Langley finds refuge in listening to podcasts about looking at art when looking at art in person becomes impossible.

And…

Navigating the constantly shifting, opening and closing of exhibitions, this issue also includes a selection of reviews: Gordon Parks, reviewed by Mark Rappolt; Rachal Bradley and Prunella Clough, reviewed by J.J. Charlesworth; Renato Leotta, reviewed by Francesco Tenaglia; Nora Turato, reviewed by Pádraic E. Moore; Hanne Darboven & Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, and Dom Sylvester Houédard, reviewed by J.J. Charlesworth. And last but not least, ArtReview sent its critics to scope out the art scenes of three cities: New York, by Rahel Aima; Los Angeles, by Cat Kron; and Copenhagen, by Rodney LaTourelle.

***Click here to subscribe***