Fatoş Üstek on why we must drop the fantasy of the lone ‘genius’ – doing so would open up a path towards healthier working conditions in the arts

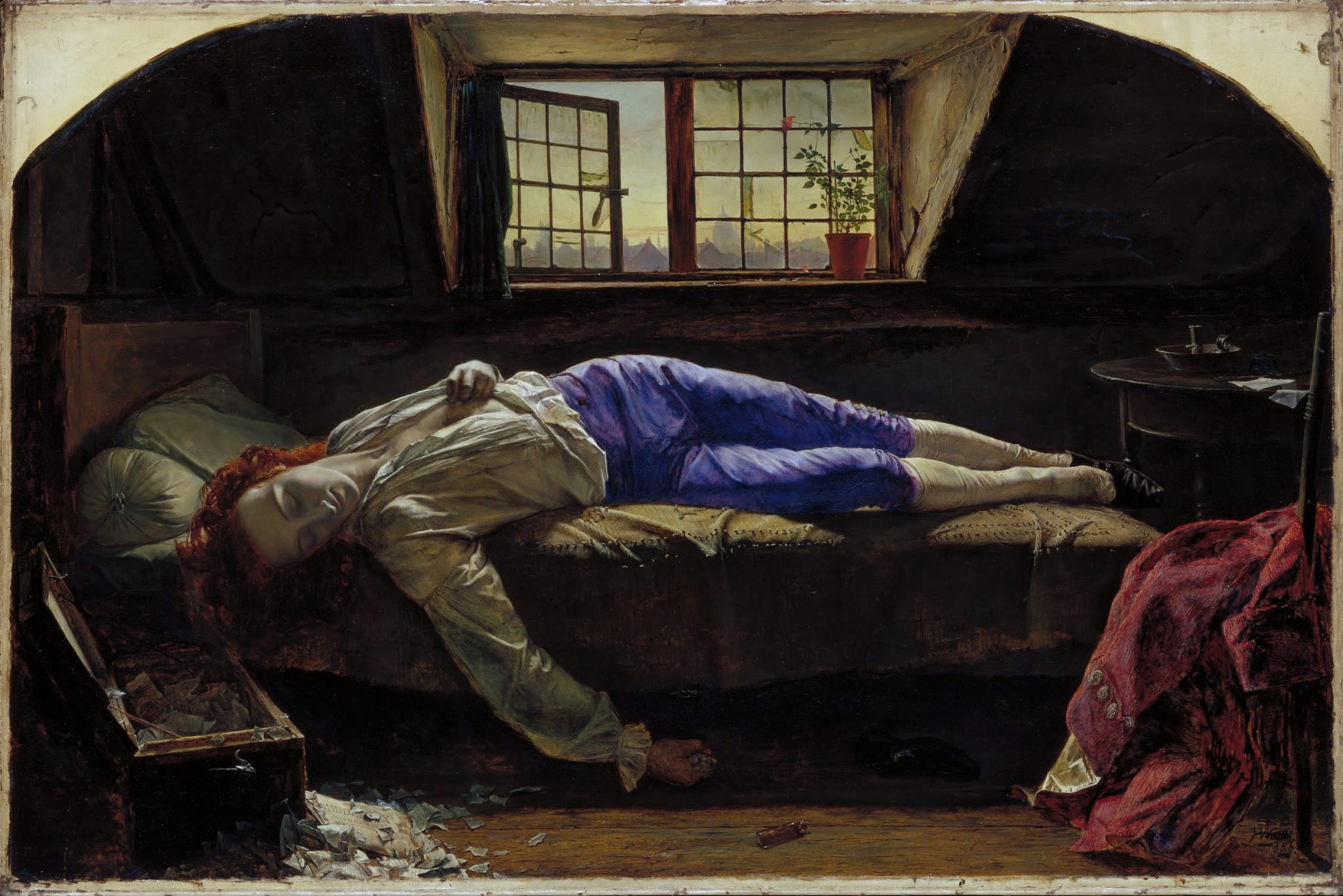

We might still cling to the romantic (and deeply problematic) fantasy of the lone ‘genius’ artist: secluded in their studio, they meditate on frothy ideas, spend their day playing with paint, and conceive masterpieces. But I beg to differ: however much today’s artists might regard their work as a solitary affair, their artistic practice is a collaborative undertaking. Given the exponential growth of the artworld’s institutions in size and scale of operations over the last few decades, even a painter who only employs canvas and oils is just one piece of a labyrinthine system of curatorial departments, gallery regulations and collectors’ expectations.

There’s a whiff of exoticism to how we like to talk about artistic labour – as a largely studio-based effort. What we need to do is expand this field of laborious engagement: to see the creative process from research and development, to proposal and assessment, from experimentation with materials to production, and then the logistics of transportation, installation and presentation of the work alongside public events. In recent years, this work has been quadrupled by fundraising needs – artists are expected to open up their studios for patrons and supporters, produce editions and merchandise, wine and dine with collectors and (of course) regularly make funding applications. Today’s artists exist within a complex web of relationships, and while they ask for the necessary conditions to display and promote their work, they must respond to the multifarious counter-demands of the contemporary artworld’s institutions in order to survive.

But while juggling these increasing pressures on their time, artists are regularly expected to agree to precarious working conditions, comparatively low pay or indeed no pay at all. There is a history to the situation they find themselves in. The mysticism of artists acting as a conduit for creativity dates back to Renaissance Europe; the idea of art as a higher calling, distinguished from mundane factory production, can be traced to the Industrial Revolution. In the UK, conceiving of artistic talent as a skill that is not unique to the offspring of bourgeois and middle-class families is an idea that only really received material support in the postwar era: the 1950s saw the proliferation of the Bauhaus-inspired Basic Course movement at art colleges (a forerunner to the Foundation Course) with greater access to arts education for working-class students; in the 1980s, Thatcher’s Enterprise Allowance Scheme offered a stable income to anyone who wanted to start their own business, benefitting some of the very well-known artists of today.

But these days, who is advocating for artists’ pay? The Arts Council-funded National Artist Association (NAA) is no longer existent (perhaps a symptom of the lack of unionisation in the UK). Artquest – the artist career development programme, set up in the aftermath of the dissolution of NAA in the late 1980s – does not have a representative function. Nor does the membership organisation a-n The Artists Information Company. Meanwhile Artists’ Union England (AUE) is a young organisation set up less than a decade ago, currently building on a membership basis. Such organisations outline hourly pay rates and day rates for artists with compensation measured in proportion to experience, starting at GBP£26,168, capped at a maximum of GBP£42,55700 per annum for those with more than ten years’ experience. (For reference, the Contemporary Visual Arts Network estimates the actual average income of an artist at GBP£15,000 per year).

Besides, there’s no legal obligation to pay these rates to artists. And a quick scan of the salaries for both temporary and permanent staff employed by arts institutions (museums, galleries, funding bodies, and so on) would be sufficient to recognise the discrepancy of remuneration for labour across the artworld. Clearly, we need to address salaries within the UK arts at large (alongside the piercing precarity of artists’ pay).

No artist shares the same career path in contemporary art, neither is it straightforward to define the role of the artists. And we should be wary about handing over the task of assigning the value of artistic labour to arts institutions. That is why I’ve worked with the artists Anne Hardy and Lindsay Seers to initiate FRANK, a new alliance for artists’ pay. The venture is born out of the urgency to work with arts institutions, empower artists and radically change the conversation around artists’ pay. We need to reflect on how the production of art has changed over the centuries, to acknowledge today’s labour-intensive demands on artists, and empower them to negotiate fairer compensation. Recent surveys have reported on the frankly terrifying conditions that artists face, especially in the wake of the pandemic (one study cited 70 percent of respondents reporting a loss of income due to COVID-19).

FRANK demands that artists’ fees be embedded in core funding for institutions, artists to be treated the same as other professionals-in-collaboration, and that funding bodies must impose a minimum artist fee requirement onto organisations they fund – with transparency throughout the entire process. Currently, we are working on a clear outline of what fair pay is and how institutions and organisations can embrace fairness in their methods of work, from contracts to working conditions for the artists. Through building a set of principles, a conceptual fair pay calculator alongside work contracts (in collaboration with an art specialist law firm), FRANK invites arts institutions to take economic equality as seriously as other issues such as inclusion and diversity. We need to change the mindset of working with artists – embracing new principles to enable artists from all kinds of socio-economic backgrounds to take their rightful place within the artworld.