Momentum 10: Nordic Biennial of Contemporary Art, various venues, Moss, through 9 October

‘One biennial to go back to emotion, one MOMENTUM to understand the need to stop and feel, to redefine the possibility of feeling’. Congratulations to Momentum, the Nordic biennial located in Moss, Norway, which after 20 years of showcasing Nordic art – and relatedly questioning what Nordic-ness might mean – has tapped the ghost of J.R.R. Tolkien to write its mission statement. As a theme, ‘Emotion’ represents a relative upswing in mood from the last one, ‘Alienation’, but it is nevertheless backed by Mordor-like darkness: in curator Marti Manen’s credible schema, we require emotionalism to militate the distance, detachment, dehumanisation, etc engendered by screen life. (The same bugbears as ‘Alienation’, in fact.) At the Momentum Kunsthall, Galeri F15 and various auxiliary venues, 29 artists will clutch the subject to their bosoms, from Annika Larsson to Gabriel Lester, Olafur Eliasson to Ragnar Kjartansson, Rosalind Nashashibi to Johanna Billing. Some of them have contributed to previous Momentums (and their earlier works will be here, reconsidered from an ‘emotional’ perspective, apparently), some haven’t. Some aren’t Nordic by any stretch: do you have strong feelings about that? Good, then.

Les Rencontres d’Arles, 1 July – 22 September

Also in specialist expos, it’s time again for Les Rencontres d’Arles, which has slimmed down its former unwieldy title so that it no longer has ‘Photographie’ in it, but maintains the same single-minded, uh, focus that it began with when, in 1970, it was founded by photographer Lucien Clergue, writer Michel Tournier and historian Jean-Maurice Rouquette (who, as of this year, have all left us). The Rencontres was predicated on showing previously unseen work, and as such has historically served as a launchpad for unrecognised photographers. But it’s also attracted stars, such as when, in the festival’s first year, Ansel Adams came to Arles to teach a photography class, and a show was held of Edward Weston’s work. This year, the Weston show is being recreated, and shown in dialogue with works by Clergue – the loss of all the founders has apparently prompted an engagement with the archives – alongside other historical surveys (eg the work of Helen Levitt), and group shows relating to walls and power, the body as weapon and constructed photography.

Hreinn Friðfinnsson, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva, through 25 August

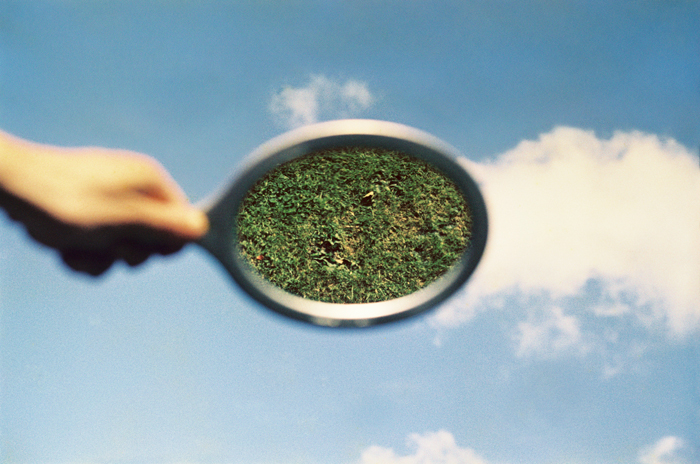

A 1973 photographic diptych by Hreinn Friðfinnsson presents, in one panel, a hand holding a hand mirror against the sky, facedown to reflect a patch of grass, while the other features the same mirror faceup on the grass, reflecting the sky. Compressed lyrical conceits like Attending are the Icelandic artist’s forte, and his entire body of work looks almost costless. For a 1974 work – which Friðfinnsson told Hans Ulrich Obrist is technically ongoing, if someone wants to call him – he placed an ad in a magazine asking readers to tell him their secrets, while by the 1990s he was making homespun formalist works from the leftovers in his studio, such as stirring sticks coated with chancy layers of paint or a spider’s web trapped behind glass. Friðfinnsson’s uncommonly flexible mind is attested to by his mid-90s works made at Mont Sainte-Victoire, France: where other artists might baulk at stepping on territory made famous by Cézanne, the Icelander strode right up to the mountain and made frottages – charcoal rubbings – of it. Geneva’s Centre d’Art Contemporain has a sideline in underrecognised artists, and so it is here. Calling Friðfinnsson a ‘kind of idiosyncratic alchemist’, they and Berlin co-organisers Kunst-Werke survey his half-century oeuvre, with To Catch a Fish With a Song: 1964–Today toggling between videos, drawings, tracings and installations, texts and readymades.

The Theatre of Robert Anton, Tramway, Glasgow, through 6 July

Actually, alchemists are in. If Friðfinnsson is an idiosyncratic one, then Robert Anton was, according to Tramway, an ‘alchemist of the mundane’. The late Texan was a key figure in the downtown theatre scene of 1970s New York, with a canny sense of how to make himself wanted (alongside his sizeable talent). He allowed a maximum of 18 people into his performances, in order that each could see up close the tiny, hyper-expressive, gender-flipping, character-shifting, meticulously sculpted puppets he used – clowns, princesses, rabbis, Nazis and figures with a bulbous third eye, all designed to pack into a couple of suitcases – and refused any documentation of them. You had to be there. Anton died of AIDS in 1984, aged thirty-five, after a decade of work. Here his brief career is resurrected – without film footage or restaging, obviously, but with the aid of some 40 of his figurines, props and associated drawings.

Julie Becker, MoMA PS1, New York, through 2 September

If you happen to be passing MoMA PS1, and you missed I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, the warrenlike retrospective of the late Julie Becker’s work at London’s ICA last year – well, you get the point, though it’s worth noting that this is an expanded version of the show. The Los Angeles artist’s work, in installation, video, drawings and more, hewed, as the title suggested, to precarity and the makeshift, whether exploring stoner lore such as the synchrony between Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon and The Wizard of Oz (in the video Suburban Legend, 1999) or, in the ‘open-ended’ series Whole that she began the same year, using drawings, photography, sculpture and video to restage the presence of a former inhabitant of her Echo Park building who had died from, again, AIDS-related complications. (Becker was allowed to rent the house cheaply in return for disposing of his possessions.) That she took her own life in 2016 after struggling with drugs and mental health issues inevitably further darkens a body of work that was dark already, but Becker’s variously involuntary and voluntary engagements with difficult living conditions, not least those of artists, feels hugely appropriate to our moment.

Dorit Margreiter, Mumok, Vienna, through 6 October

The relationship between social space – particularly as incarnated in architecture – and psychological pressure has been a concern of Dorit Margreiter’s for years, as has been ‘the connection between visual systems and spatial structures’, which for her has often meant Modernism and its aftermath. Not entirely surprising then that, for her solo show at Mumok, the Austrian artist – now in her early fifties – has chosen to make the architecture of the exhibition space part of the show, though her gaze also broadens out to other Viennese landmarks. The central aspect of the show is a film shot in the hall of mirrors in the city’s amusement park, the Prater; further disorientation, and implication of the venue, transpires via a mobile also made of mirrors. Elsewhere, the imprint of Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi’s architectural theorising on Margreiter’s thinking is made apparent by Boulevard (2019), a filmic visit to Las Vegas’s Neon Museum, where the city’s signs go to die. And just in case you think she’s not committed to her themes, she’s titled this concatenation of works Really! No, really.

Kim Gordon, Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, through 1 September

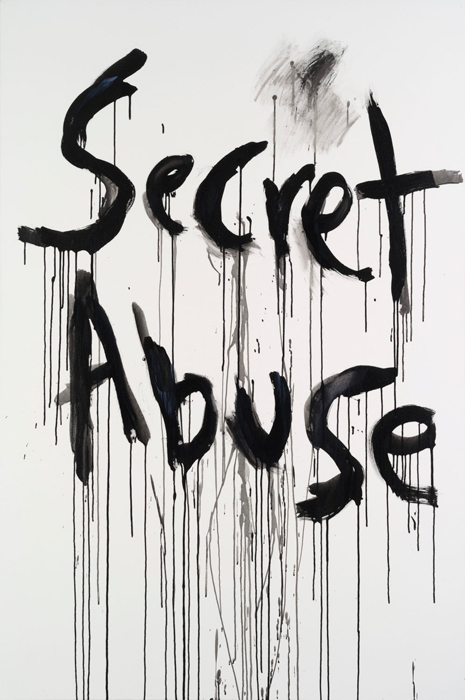

This writer once interviewed Kim Gordon about her art. It was about 15 years ago, the erstwhile Sonic Youth bassist and feminist alt-rock icon hadn’t really dug into her artistic career – not least because her main band was still extant – and she was endearingly shy about it. Since then, the art school-trained (at Otis, in California) Gordon, who worked for Dan Graham early in her career and in fact had her first solo show in New York in 1981, has earned renown for her spiky, provisional, typically text-driven paintings, which sit neatly in a lineage of laconic daubing by the likes of Michael Krebber and her frequent collaborator, Jutta Koether. Punk rock, as rephrased by Gordon’s art, is leaving wide acreages of canvas blank and then scrawling the name of, say, her late friend Mike Kelley’s old band Destroy All Monsters on it, or a deadpan quote from Jerry Saltz. Such works, ‘An encyclopaedia of cool’ according to Garage Magazine, are short on looking time but long on an afterglow of attitude. For Lo-Fi Glamour, and as befits a first US retrospective taking place at the Andy Warhol Museum, Gordon incorporates sculptures using silver glitter as well as a sound and video installation and a newly commissioned score (also available as a record); and she cites Warhol’s cross-media activities as a foundational inspiration. Meanwhile, factoring in her much-admired 2015 memoir, Girl in a Band, it’s increasingly looking like Sonic Youth was just Gordon’s first act.

Mayo Thompson, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin

Mayo Thompson, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin, 28 June – 17 August

As a musician-slash-artist, though, Gordon is arguably bested by Mayo Thompson, first of legendary experimental rock outfit The Red Krayola during the mid-60s, then a collaborator with Art & Language, then a record producer, then a musician again, then an art teacher (at Art Center in Pasadena). Throughout that time, as the miniretrospective Thompson had at Galerie Buchholz in 2016 demonstrated, the Houston-born hyphenate has made art: droll linear illustrations for books, charcoals related to nautical matters, watercolours of birds. In 2012 – at the tail end of an engagement with German artists, first figures such as Martin Kippenberger and Werner Büttner, and, later, the aforementioned Krebber – and following a revival for his music during the 90s, the worlds he straddles were bridged via a ‘continuous’, Skype-enabled performance by The Red Krayola during the Whitney Biennial, and in 2015 he had his first solo show under his own name. No word yet on which way the cards will fall for his second Berlin show with Buchholz, but it’s unlikely to feel like the work of a man in his mid-seventies.

Roman Signer, Kunsthaus Zug, Switzerland, through 15 September

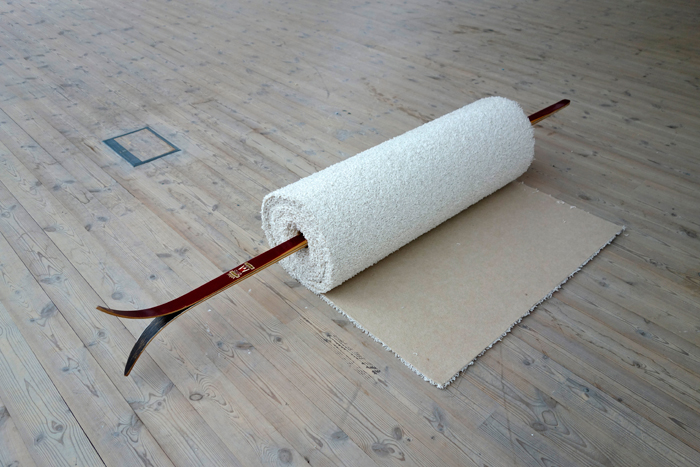

Prior to turning to art at the relatively late age of twenty-eight, Roman Signer spent a bit of time working in a pressure cooker factory, and you suspect this had as much of an effect on the Swiss sculptor’s aesthetic sensibility as anything else. For decades, Signer has made works that explode, or cause objects to soar through the air, or simply travel through space, for all that these dramas often take place in front of a video camera. In Action Kurhaus Weissbad (1992), he sent chairs flying through a hotel’s windows; in Kayak (2000) he was towed down a road in a canoe; in the 2008 video 56 Small Helicopters, the titular remote-controlled vehicles bounced off the walls and ceiling of a room and smashed into each other until all were prone on the floor. At Kunsthaus Zug, which is proud to own a large number of Signer works, expect a robot lawnmower roving the floors of the gallery, sometimes dinging a bell, and a number of new works that, we’re told, constitute the calmer side of his practice, containing – rather than explosivity – tenderness and poetics. If you’ve scanned a newspaper recently, you might have noticed that our planet is dying.

Mark Dion, The Hugh Lane, Dublin, through 1 September

Mark Dion, whose art has trended towards a form of institutional critique that mimics and inverts the layouts of natural history museums in order to query taxonomic logic, has signalled the dangers of imposing human schemas on nature since the 90s; at The Hugh Lane, using a title, Our Plundered Planet, that chimes with the Extinction Rebellion movement, he’s being fairly unambiguous about it. Deploying wunderkammers, a natural-history bookstall and stuffed animals, Dion frames man as an unhelpful dominator: should all this sound preachy (and I-told-you-so), the institution points out that it’s all done with ‘a dose of humour and playfulness’. Gallows humour by this point, one might assume.

From the Summer 2019 issue of ArtReview