Now! Young Painting in Germany, Kunstmuseum Bonn, Museum Wiesbaden, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz – Museum Gunzenhauser, 19 September – 19 January

Taking the pulse of contemporary painting has been in vogue in recent years: the more expansive frameworks include MoMA’s The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World (2014) and the Hayward Gallery’s Painting 2:0: Expression in the Information Age (2016).Now! Young Painting in Germany – is a bigger show than those – 53 artists and 500 works across three venues (with the highlights touring to the Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, in 2020). Though it’s also, as you might surmise from the title, not as internationalist. Aside from all the participants being from Germany, the show aims at surveying the venerable practice of painting according to two other constraints: there’s no truck with ‘expanded painting’ – no installation, no multimedia – and all the participants were born during the late 1970s or after. Germany, as is well known, has produced successive waves of major painters for a very long time: here’s an opportunity to see what the next upsurge – if it is one – looks like, via figures including Cornelia Baltes, Florian Meisenberg, Jana Schröder and a large number of artists who, admittedly, I haven’t previously heard of.

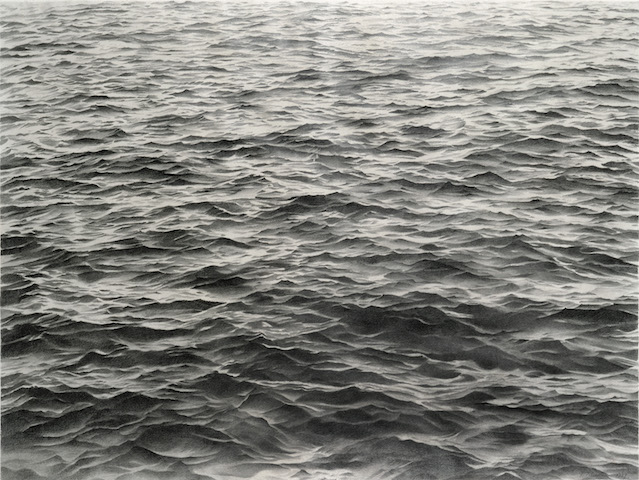

Vija Celmins, Met Breuer, New York, 24 September – 12 January

It’s a long time since Vija Celmins had to prove herself: now in her eighty-first year and a half-century into her career, the Latvian-born, longtime US-based artist is at the coronation stage, and like, say, Ed Ruscha, she’s one of those artists upon whose excellence most people with eyes agree. To Fix the Image in Memory, which spans some 120 works, is unlikely to dent her reputation. It’ll be a primer in philosophical quietude, in using seemingly simple means to open onto huge ruminative plateaus: rippling oceans, night skies, moons, spiderwebs. Celmins’s silkily monochromatic art, which emerged out of an engagement with Pop and Photorealism, and also dips into sculpture, drawing and print, always borders on abstraction, and continually tilts metaphorical. Most of all, what it conveys is awestruck atmosphere, seeming to contain vastness within a single meditatively rendered image, and also, harkening back to the ‘all-over’ technique of Abstract Expressionism, to present each scenario as a fragment of a much larger whole, almost randomly chosen, so that gravitas runs up against a strange indifference, something like that of the universe looking back at us.

Ugo Rondinone, Kunsthalle Helsinki, 17 August – 17 November

Vocabulary of Solitude could be an alternative summation of Celmins’s work. Instead, it’s the centrepiece sculpture, from 2014, of Ugo Rondinone’s retrospective in Helsinki, featuring 45 versions of the Swiss artist’s leitmotif: sculptures of hyperrealist, serious-looking clowns, going through a range of mundane daily activities, from breathing to dreaming to farting to peeing. These lachrymose figures, carrying on their lives midway between gaiety and depression, are stand-ins for you and me as much as are Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon, and are typical of the Swiss artist’s work in shuttling between binary states. The show as a whole is perked up by a number of his rainbow-themed works, the subject retailing its myriad meanings: the window decal love invents us (1999) and the polychromatic text work (and show title) everybody gets lighter (2004) have an upbeat vibe, but then we’re bumped back downward with a scatter of empty clown shoes. Given these dynamics, Rondinone’s work often operates best at scale, where his shows can feel as if they contain a lot but are still somehow emptied-out – or maybe that’s just a glass-half-empty writer talking, and, like the thousand Finnish schoolchildren who’ve lined one room with floor-to-ceiling drawings of, yes, rainbows (the latest iteration of your age and my age and the age of the rainbow, 2014–), you’ll come away with afterimages of kaleidoscopes of colour.

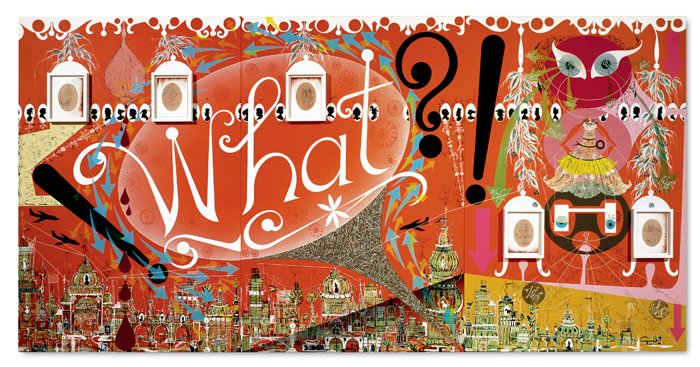

Lari Pittman, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 29 September – 5 January

Speaking of which, Lari Pittman is having his biggest retrospective in 20 years: some 80 paintings and 50 works on paper. So it’s going to be rich, because one painting by the Los Angeles artist (and, as the press materials are keen to point out, revered teacher) is enough to keep you going for a while. Pittman is an effervescent maximalist, packing his canvases with cannily interlocking phantasmagorias of imagery and ornament, and surfing across categories: his work has an effervescence to it, reflecting its roots in a time when LA artists were reclaiming decoration, but also – having reflected on the AIDS crisis and racial violence – a heaviness that is placed in conversation with the ‘sunshine and noir’ tendency of the city’s artists during the 1980s and early 90s. More latterly, he’s pivoted to dreamscapes and internal monologues. Expect, here, alongside scads of canvases, the occasional sculpture and collaborations with the likes of experimental novelist Dennis Cooper.

Bergen Assembly, various venues, 5 September – 10 November

The latest Bergen Assembly has gone all out for jolliness by calling itself Actually, the Dead Are Not Dead. It not being Halloween yet, that really could be a positive statement, and indeed the latest edition of this triennial in the salubrious Norwegian city is intended as a cumulative prod for us to reassess our relationship with the no-longer-living and consider how, or in what form, they stay with us. Beyond that, it’s heftily philosophical in a way that can’t easily be summarised here (Jacques Derrida and Judith Butler come into it), and the lengthy curatorial statement doesn’t mention any artists, perhaps because those figures included are considered as ‘contributors’ and cross all kinds of disciplines. The project also enfolds and continues the antifascist, transfeminist, antiracist ‘Parliament of Bodies’ discursive platform originated by Paul B. Preciado and Viktor Neumann as the public-programmes aspect of the last Documenta. Aside from that, expect ‘contributors’ ranging from Alexander Kluge to Imogen Stidworthy, Banu Cennetoğlu to Hiwa K to Francisco de Goya (who?).

Kaari Upson, Kunstverein Hannover, 7 September – 17 November / Kunsthalle Basel, 30 August – 10 November

‘It was always my intention to take facts and kind of contaminate the shit out of them,’ Kaari Upson told Flaunt magazine earlier this year, in the runup to her inclusion in the Venice Biennale. The American artist’s European incursion continues with a pair of institutional shows, and furthers her multimedia transubstantiations of memory. It seems not insignificant that the San Bernardino neighbourhood in which she grew up was later devastated by wildfire; her best-known work, the multitiered (drawing, sculpture, video, performance) The Larry Project (2004–11), used and reimagined elements of the life and effects of a man who lived on her street, and her new works are based on elements of her parents’ home and other houses and trees on her street, often involving latex casts as the basis for moulds and estranged further through technical processes, including shimmering veils of colour. At the same time, though, Upson expands this beyond a mere inability to return to or fully understand the past: her work, the Kunstverein Hannover asserts, ‘directs a dissecting artistic look at herself as a representative of a white social class and its abysses’.

Gabriel Kuri, WIELS, Brussels, 6 September – 5 January

Gabriel Kuri, who has lived in Brussels for 16 years, is finally getting his first hometown institutional exhibition. At WIELS, sorted, resorted will play to the Mexican artist’s strength: gathering a heterogeneous glut of materials from here and there and arranging them according to his own organising principles. Here, his categories are paper, plastic, metal and construction materials. Kuri’s process across these 60 works serves, to some extent, as a reflection on the fluidity of value: in the past, through formalised display, he’s transmuted everything from oysters to lottery scratch-cards to drinks cans, skips to rocks to receipts. But he’s also in conversation with Surrealism, and a good deal of his work – which encompasses sculpture, collage, installation and photos – operates through unlikely juxtapositions and symmetries, making ordinary objects hum with newfound strangeness, grace and fundamental visibility.

Clare Woods, Simon Lee, London, 6 September – 6 October

‘Doublethink’ is, of course, George Orwell’s term for ‘the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and believing both of them’. If this hasn’t been used as a framing device for painting before, it’s surprising; in any case, Clare Woods has alighted on it as the title for her debut solo exhibition in London, at Simon Lee. It’s a strong fit. Woods, who started out as a sculptor, has since the mid-1990s practised a particularly materialist mode of painting: beginning by focusing on landscape and shifting her attention to the human body, she’s continually made works where image and paint are in counterbalance. For everything you look at, you’re equally aware of the stuff from which it’s composed; for every figurative reference, half the painting seems to be dissolving into abstraction, the colours somehow both sumptuous and queasy; and everything she paints – figures, flowers, mirrors – is treated with the same quizzical distance, filtered through process. The result is probably less doublethink than sextuplethink, and darkly pleasurable.

Foncteur d’oubli, Le Plateau, Paris, 19 September – 8 December

Maths nerds! What’s a forgetful functor? That’s right (I open Wikipedia) ‘in the area of category theory, a forgetful functor “forgets” or drops some or all of the input’s structure or properties “before” mapping to the output’. Or it’s a thing that moves something from one category to another. But that’s not all: it’s also a notion that’s now been borrowed by an artist-curator, Benoît Mare, to add intellectual gravitas to a show about, indeed, category switching. OK, that’s snide. Foncteur d’oubli, which specifically looks at the relationship between art, design and architecture and whether functionality is a determining factor in those categories, looks savvy, history-aware and very good. It tracks back to modernist figures such as Eileen Gray and Robert Mallet-Stevens and early combinations of art and architecture in search of the ‘total artwork’, and explores how this ideal has influenced successive waves of artists. The artists here engage with design, the designers skew towards a nonreproducibility that has artlike overtones, the architects prioritise a tailored use of materials for individual needs. Expect figures and groups including Nina Beier, Marcel Broodthaers, Diego Giacometti, Martinez Barat Lafore Architectes, Van Wassenhove Atelier and the legendary ‘ceramics from a private collection’.

Kreislaufprobleme, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 13 September – 12 October

Enough maths; looping back to where we began, German class is in session. Kreislaufprobleme, literally meaning circulation problems, constitute a perennial, almost in-joke excuse when German workers don’t want to go to work. As guest curator at Croy Nielsen, though, Anna Gritz is using the phrase with serious intent: inspired additionally by a slippage of language in a short story by Rita Valencia – where a woman says ‘bag’ instead of ‘back’, seeing her body as a container of pains – and by Ursula K. Le Guin’s identification of the bag as the first cultural device, she’s assembled a show in which meaning circulates problematically, uneasily, between bodies and bags. Expect her six artists (Leda Bourgogne, Liz Craft, Stuart Middleton, Liz Magor, Ser Serpas, Angharad Williams) to variously adumbrate socioeconomic pressures on the body, explore mistranslation, transmute found objects. Of the various shows in Vienna’s annual ‘curated_by’ season, this one looks like our bag.

From the September 2019 issue of ArtReview