Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, various venues, Los Angeles, 15 September – January

We like a vast and unpredictably timetabled exhibition project that bites back, so hats off to Pacific Standard Time for calling their second manifestation in seven years LA/LA. Yes, Los Angeles has been dubbed ‘La La Land’ forever. But it’s notable that PST adopted their title in the wake of an eponymous, very successful, ethnically nondiverse Hollywood musical, and that the myriad shows in la/la – nearly 80 of them – consider, among other foci, ‘luxury objects in the pre-Columbian Americas, 20th-century Afro-Brazilian art [and] alternative spaces in Mexico City’. The title, of course, also neatly suggests manifold LAs, just as Pacific Standard Time’s mission seems to be to excavate alternative histories of Southern California and its peoples, plural. Expect, in exhibitions stretching across scales (museums, university galleries, performing arts centres, etc) and the region (‘Santa Barbara to San Diego, Santa Monica to Palm Springs’), everything from Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano la in multiple Los Angeles venues, to Latin American kinetic art at Palm Springs Art Museum, to a David Lamelas solo show at the University Art Museum in Long Beach.

Moscow Biennale, various venues, Moscow, 15 September – 28 October

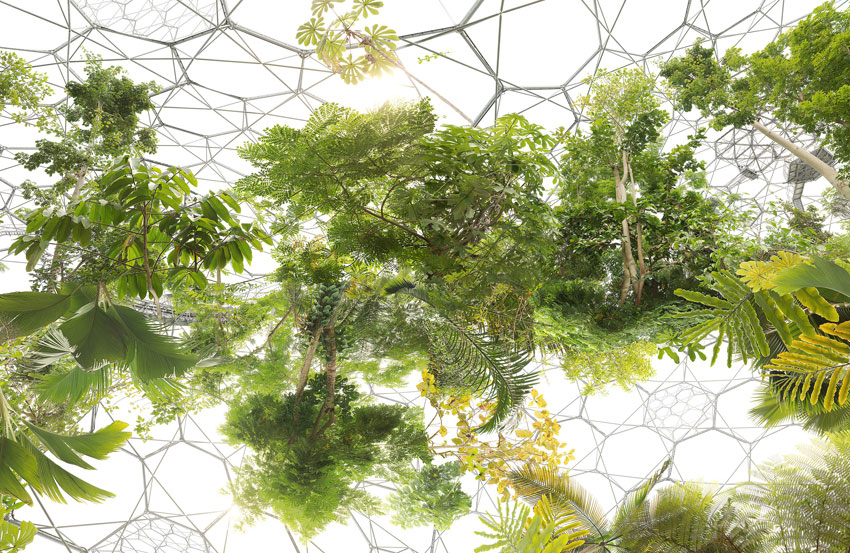

The latest Moscow Biennale, curated by Yuko Hasegawa – here branching out from directing biennales beginning with ‘S’ (Sharjah, São Paulo, Seoul, Shanghai) – is titled Clouds / Forest, two things Russia has plenty of. Yet Hasegawa’s show, which radiates outward from the Manezh exhibition hall near the Kremlin, isn’t so literal. It’s themed around the idea of ‘creative tribes’ who are connected across geographical borders, perhaps see themselves as stateless and are necessary at a time of global crisis like this. The forest, then, is some kind of metaphor for the global movement of people, and statelessness, and the clouds above it represent the Internet: ‘It is between the forest and the cloud that new meanings and masterpieces are created,’ says Hasegawa. This would seem to offer scope for artistry that, variously, skews digital and reacts against immateriality, and even though the artists’ list is currently hiding behind a cloud that reads ‘coming soon’, and despite the historical pitfalls of exhibiting in Russia in general (see, for example, Manifesta in St Petersburg), we’d bet on Hasegawa to pull off something noteworthy.

Art Without Death: Russian Cosmism, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 1 September – 3 October

Russia, at the dawn of the modern era, saw a movement emerge entitled Cosmism. The brainchild of Nikolai Fedorov, a heady mix of scientific and Russian Orthodox thought aimed at space travel and the overcoming of death via technology, its influence has waxed and waned over the years – plunging underground not least in the Soviet era, when Fedorov’s theoretical texts were banned. Right now, though, it’s ascendant again, being picked up by accelerationist thinkers, among others. In Art Without Death: Russian Cosmism, which promises to be a classically essayistic Haus der Kulturen der Welt presentation (with exhibition design conceptualised by Hito Steyerl), we’re offered a tour of Cosmism’s historical and present-day effects: loaned Russian avant-garde works apparently influenced by the movement, selected by Boris Groys and including art by Vasily Chekrygin, Maria Ender, Ivan Kudriashev and Aleksandr Rodchenko, a film trilogy by Anton Vidokle orbiting around the subject titled Immortality and Resurrection for All (2017), an artwork-cum-library by Arseny Zhilyaev and, naturally, a conference.

Adam Jeppesen, Martin Asbaek Gallery, Copenhagen, 21 September – 21 October

Clearly not a party person, Adam Jeppesen has over the past decade spun large-scale photographic projects from his activities as a roaming solitary. The Danish-born, Copenhagen- and Buenos Aires-based artist’s calling card series/ book, Wake (2008), was assembled ‘in the secluded backwoods of Finland’ from photos made during seven years of nomadic wandering – resolutely minor-key images including overcast landscapes, spectral power lines, flickering shadows on old interiors – and merged a German objective documentary approach with something more impressionistic, mood-driven. A later series, Flatlands (2015), documents a 487 day journey from the Arctic to the Antarctic, down through North and South America, leaving society behind in the process and once again mixing the urge to document – to prove what he did, even – with a subjective overlay. Here, Jeppesen allowed his negatives to get scratched, and manipulated the ensuing prints in various ways, from linking multiple sheets to sticking starry constellations of pins in them. In his latest series, The Pond (2017), the landscape that was maybe always a cipher for an interior world has disappeared, though Jeppesen’s attention to analogue photography persists. He’s been making cyanotypes, on linen, of hands, gesturing obliquely but intently – images that feel, technically, like they could have emerged from any moment in photography’s continuum, their subjects freefloating in time.

Chantal Joffe, Galleria Monica De Cardenas, Milan, 28 September – 25 November

Few painters today can pull off the kind of astringent psychological portraiture mastered by Maria Lassnig and Alice Neel; Chantal Joffe, who perhaps not coincidentally shows at Victoria Miro (which represents Neel’s estate), is one: and like Lassnig, the St Albans-born artist often focuses – unsparingly – on herself. In a recent interview, she described herself as looking, in one painting, like an old banana. (Oddly, in another canvas, from 2012, she pictures her partner, the painter Dan Coombs, eating the same fruit.) In the 21 years since she debuted in Britain’s annual New Contemporaries exhibition, Joffe has built an oeuvre keyed to motherhood and self-portraiture. Her style is a kind of virtuosic, melty smear-and-daub where everything nevertheless resolves into place and rides along on hot, insistent colour, and where interior lives forever rise to the surface of the face. In her first show with her Italian gallery in seven years, don’t expect that to change; her paintings, though, remain fresh because they’re translations of palpably vivid vision.

Hans Bellmer, Sascha Braunig, Matthew Ronay, Office Baroque, Brussels, 7 September – 21 October

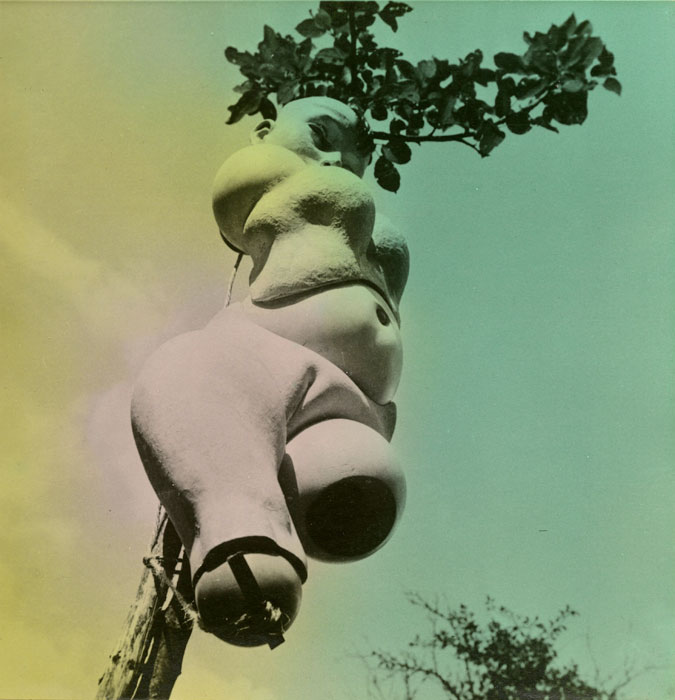

The award for oddball exhibition of the month (a category we’ve admittedly just invented) goes to a tripleheader at Office Baroque: Hans Bellmer, Sascha Braunig, Matthew Ronay. One connection for this time- and aesthetic-spanning show might be the presence, or suggestion, of models: the Canadian painter Braunig uses them, lit with coloured gels, to make her sheeny, technically superb trompe-l’oeil canvases, figures interlaced with Op-art patterning, inhabiting an interzone between Surrealism and CGI renderings. Bellmer, of course, based his chiaroscuro photographic art around his creepy relationship with pubescent female dolls. And virtually everything Ronay makes feels like a cartoon, or a model of something, his sprouting forms and totems evoking castaways from some fantasy territory, maybe Loompaland. Expect the unnerving and the childlike in equal measure – not that children can’t be unnerving anyway.

Martin Puryear, Parasol Unit, London, 19 September – 6 December

In London, a belated righting of wrongs. Martin Puryear is finally receiving an institutional show, at Parasol Unit: one covering four decades of his brilliantly allusive and elliptical sculpting practice, augmented by works on paper. If Puryear has a parallel in the uk, it’s probably the so-called Lisson sculptors, particularly Richard Deacon and Tony Cragg, in their catholic approach to materials and organic, edge-of-recognition fuzzing of abstraction and figuration. But Puryear’s work is predicated on issues of race, liberty, injustice: see, for instance, the black ironwork Shackled (2014), which is half crouching creature, half restraint, elegant and ominous, or the meticulously veneered red cedarwood Big Phrygian (2010–14), which looks like a recoloured Smurf’s cap but refers to a headgear signifying resistance in the French Revolution and freedom in the American one. A 2.5m outdoor bronze here is titled Question (2013–14), and to an extent, that’s the subtitle of all Puryear’s work. Art’s job isn’t to give answers but to formulate better questions, the saying goes. These are better than most.

Iran do Espírito Santo, Sean Kelly, New York, 8 September – 21 October

Iran do Espírito Santo also makes meticulously honed, near-abstract sculptures that echo the real. But the Brazilian’s artworks, manifesting on all kinds of scales, are less internally troubled than they are a kind of consoling balm, an honouring of the everyday that sands off the details and leaves Platonic ideals. A numbered series of marble works from 2011–12, all entitled Globe, look a bit like sealed bowls, or cakes on stands, or objects that a Buddhist monk might meditate in front of. A series from 2014 depicts dropper bottles, in monochromatic coloured glass or brushed steel, that are unopenable and hieratic, as if the act of, say, applying eyedrops had been elevated to an empyrean realm. A flat-ended lightbulb, similarly translated into stainless steel, becomes a gnomic, gorgeously still thing; while in a series of larger in situ painting interventions like Switch (2012), Espírito Santo creates the illusion of a soft, chasmal rectangular indent filling an expanse of grey, paired with a glowing white concavity. Go (to Sean Kelly, specifically) and feel a high-toned, smartly prepared becalming, if only temporarily.

Josephine Meckseper, Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City, 22 September – 28 October

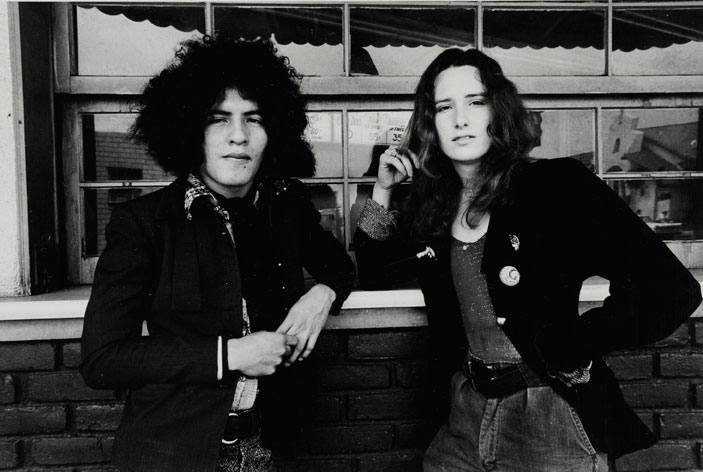

And then, to undo that calm lickety-split, there’s Josephine Meckseper, whose work is deeply worldly: vitrines and shallow glassed boxes resembling window displays that refract subconscious urges through the prism of consumerism and the relentlessness of capitalism per se. (A characteristic work from 2006, titled Blow Up (Michelli), paired partial mannequins clad in women’s underwear with a toilet scrubber and a sign reading ‘endless deals’.) When she moves outside her stylistic wheelhouse, the German artist augments her blackly poetic tour of contemporary ills: in 2012 she installed sculptural oil derricks in Manhattan, and even her latter-day paintings, gridded suggestions of skyscraper windows serving as a structure for zipping blue smears, have an undertone of violence about them, as if moments from being smashed. Indeed, for all its stillness in the gallery, it’s the grim about-to-kick-off vibe of Meckseper’s work that really powers it – underscored by photographs, variously staged and documentary, that consider the history of protest and the counterculture’s muzzling. As capitalism becomes ever more convulsive, it only veers closer to where she’s already standing.

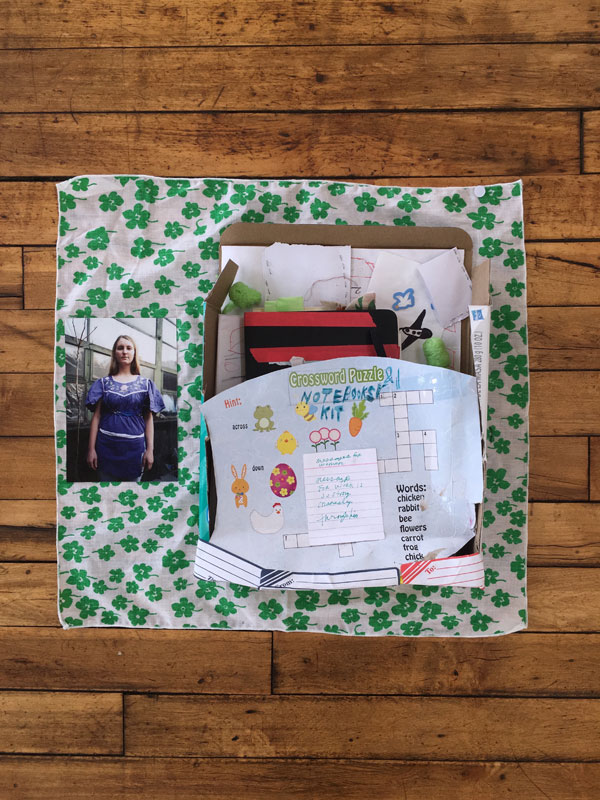

Susan Cianciolo, Modern Art, London, 1–30 September

‘I feel like it has taken the past 20 years just to sit in my shoes,’ said Susan Cianciolo in an interview a while back. That’s what happens, or used to, when you’re an artist who’s successful in fashion first, even if your fashion is filtered through an artistic mindset and seen, not infrequently, by the fine-art crowd. Barred by her family from going to art school, Cianciolo became a designer instead, but her first runway show was at New York’s Andrea Rosen Gallery in 1996, and she worked with Kim Gordon on Gordon’s label X-Girl, intersected with the skater crowd, sometimes included spoken-word performances in her presentations of collections and showed Fluxus-related art at a Tokyo gallery. Since the artworld has become relatively borderless, and recently fashion has also swung towards Cianciolo’s rough-edged mix-and-match style, she’s been included in Greater New York (2015), participated in this year’s Whitney Biennial and, after showing with Bridget Donahue (Fluxus-like boxes containing her archival materials), has another gallery show, in London, with Modern Art – whose director, Stuart Shave, began his career as a dealer in the 1990s by showing work that drew on skater, graffiti and fashion subcultures: a perfect circle. Cianciolo, meanwhile, is also making tapestries, homeware collections, whatever she likes. Someone send out for a box of hyphens.

From the September 2017 issue of ArtReview