How does contemporary art contribute to our awareness of big issues? Sometimes, like this: in the latest project to feature contemporary art and outer space (there have been a few), the African Art Space Project will commission an artist from Africa to create an image, to be applied to the nose cone of an Ariane 5 rocket launcher. Blasting off in 2021, it will deliver a European meteorological satellite into orbit, which will observe the African continent and collect meteorological data about how Africa is being affected by global warming.

What art in space does best is show up the tensions of the artworld’s attitude towards it being a visible culture, with access to the most elite levels of economic, social and cultural power

If you’re wondering how anyone will see an artwork on the nose cone of a rocket which will be travelling at 25,000 kilometres per hour and then be jettisoned to plummet to earth, you’ve missed the point. According to the Project’s initiators, African Artists for Development (AAD), a foundation set up by French art collectors Matthias and Gervanne Leridon (they’re passionate about contemporary art from Africa), the work will be toured across Africa, before being fired into space. It’s a symbolic act, the first work of African art in space, a ‘powerful symbol of the continent’s artistic power’, incarnating the ‘image of a modern, ambitious, optimistic Africa that take us beyond the stars.’

Space is a strange place to want to send contemporary art, though it doesn’t stop artists (and art collectors) wanting to do just that. Yet maybe what art in space does best is show up the tensions of the artworld’s attitude towards it being a visible, influential culture, with access to the most elite levels of economic, social and cultural power. And, like misfiring rocket launchers, it produces its own spectacles of disappointment. Trevor Paglen’s Orbital Reflector, a 100-foot-long diamond-shaped balloon compacted inside a satellite, was launched into space on 3 December 2018. Unfurled, the work would have been visible from earth. According to its commissioner, the Nevada Museum of Art, Orbital Reflector would help ‘change the way we see ourselves… and our place in the world’. For Paglen, this purely artistic gesture would encourage the world to ask ‘serious questions about who controls space: Does anyone own it? And who ultimately decides how it is used?’

As it turned out, due to the US government shutdown of early 2019 (caused by Donald Trump’s standoff with Congress), the tiny device that would have deployed the work couldn’t be given authorisation by the FCC. Running out of power, it now floats lifeless in earth orbit.

But regardless of their success or failure, these art-in-space projects stand in uneasy relation to the power and privilege that enables them. Ironies abound, since while these projects may raise big questions, such questions are full of equally big social and political issues that show up art’s relatively slow and secondary ability to respond to them. After all, we should all want a ‘modern, ambitious and optimistic Africa’. Who wouldn’t? But what that really demands is an economically vibrant, prosperous and wealthy Africa, and that might mean a few more CO2 emissions, to eradicate human poverty and want from this poorest of continents. Meanwhile, Ariane 5 rockets are launched from French Guyana; a country in Latin America, remember, which is still an ex-colonial territory of France, still run as a department of the French State, and uses the Euro as its currency. Fine words by wealthy French art collectors about the ‘power of African art’ don’t resolve the still-existing power relations between the powerful West and the weaker African continent. (Maybe, too, a project to send a work of African art into space would have had better optics if it wasn’t funded by donations of artworks by African artists.)

Paglen’s Orbital Reflector – launched on one of Elon Musk’s SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets – is also full of unintended ironies. Musk’s SpaceX company has the vaunting ambition of making space launches cost effective, to make his personal ambition of seeing humanity colonise Mars more achievable. Yet in today’s more downbeat and self-critical culture, humanity going to space is often seen less as a noble and optimistic vision of humankind and more of an opportunity for humans to pollute the cosmos with the same shit with which they’ve littered the Earth. As T.J. Demos grumbled in a recent issue of e-flux journal, Musk’s ‘libertarian entrepreneurialism’ is another aspect of ‘a growing “colonial futurism” premised upon the neoliberalization of outer space’, ‘set on off-planet resource mining, terraforming other planets, and extending property claims far into the galaxy.’ For Demos, ‘with the neoliberal corporate-military-state complex determined to occupy and settle the very place that certain Afrofuturists have long sought as a destination to escape colonized Earth, such starry-eyed fantasies are quickly becoming grim futures.’

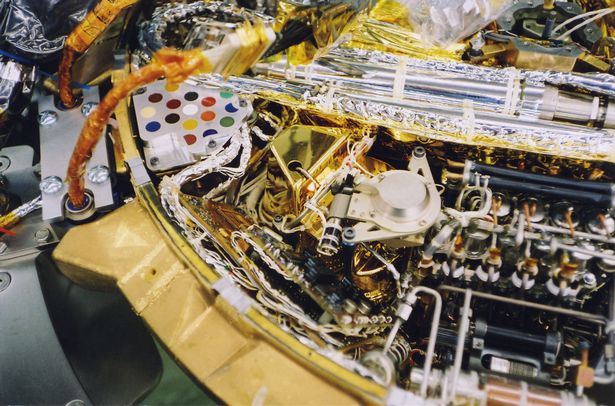

Artists often reflect and project the preoccupations and anxieties of their moment. Now artists worry about the environment and colonialism. The first artwork on the Moon, Fallen Astronaut (1971), by Belgian Paul Van Hoeydonck, memorialised the 14 Americans and Russians who had died in the attempt to explore space. It still embodied the sense of human significance in that project. Damien Hirst got to Mars before Elon Musk, his spot-painting-derived panel attached to the Beagle 2 Mars explorer in 2003. Its cheery cynicism said little about space and more about Hirst’s thirst for self-publicity.

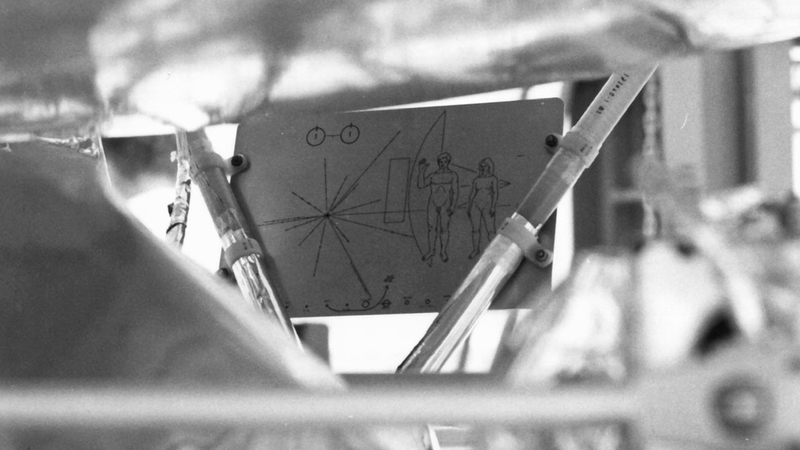

The greatest work of human culture in space, if it still exists, isn’t even an ‘artwork’. It’s the information panel bolted to the side of the Pioneer probe launched in 1972. Marked with schematics of Earth’s position in the universe, stylised images of a man and a woman, it’s not an attempt to communicate with ourselves, about our own worries, but to others, to say hello.

Online exclusive published on 9 August 2019