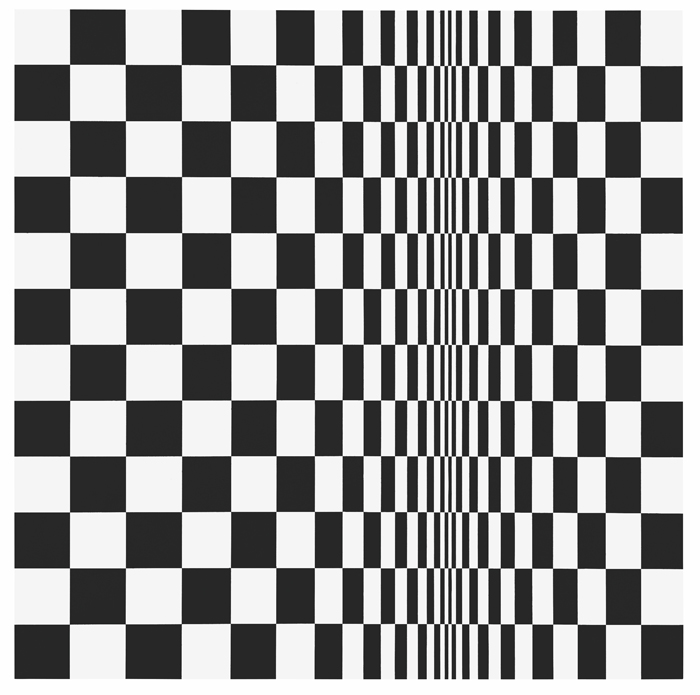

Bridget Riley at Hayward Gallery, London, 23 October – 26 January

It’s a truism that paintings don’t really work in reproduction. Bridget Riley’s do: onscreen, their perceptual shimmer can make static images feel like animated gifs. But they’re even better in reality, where one can be engulfed by their scale. As her first London retrospective in 16 years will reconfirm, Riley’s work is also resistant to time. Early Op breakthroughs like 1961’s Movement in Squares – a chequerboard pattern emerging from or disappearing into a vertical abyss, painted when she was thirty – have lost none of their Apollonian dazzle; such works scent of the 60s, for sure, but also operate in a perpetual present. The Hayward show will track the stately shifts in her art, from her increasing use of colour after the mid-60s, to her compositional innovations: the vertical stripes of the 70s, the almost digital-feeling gridded parallelograms of the 90s, the interlocking Matissean shapes of the early 2000s. Those paintings dance, and Riley, now nearly ninety, may be unparalleled among living painters in her grasp of visual rhythm. This show, accordingly, will be a lift, and – tricked out as it is with her early figurative paintings, works on paper, recent wall paintings and Riley’s only sculpture, Continuum (1963/2018) – an education.

Stanley Whitney at Lisson Gallery, London, through 2 November

Across town at Lisson, meanwhile, another master abstractionist treads the boards. Stanley Whitney has geometry and colour in common with Riley, but that’s about it. For years he’s doggedly pursued one format, stacks of building-block squares on thick horizontals, wrapped up in sociably loose handling and eye-popping yet nuanced tonalities. Whitney’s work is heavy on pleasure, but also complication. In these Afternoon Paintings, smaller than he usually works, he’s tended to begin with a single black square, a sort of weight in the painting around which he improvises. (His work often invokes comparisons to jazz.) His instinctive process sets in motion ours: there’s a feeling, in the work, of great stability that licences the eye’s wandering happily from one colour to its complementary or contrasting neighbour, and a strange sense of event in the works’ offbeat modulations through a rainbow of tones and scalar shifts within the approximate grid. As the title suggests, Whitney can apparently complete one of these in a few hours, after which he’s done for the day, coming back tomorrow both knowing and not knowing what he’s going to do. This man has life figured out.

Charlotte Posenenske at MACBA, Barcelona, through 8 March

Charlotte Posenenske quit the artworld in 1968, but the artworld won’t quit her. The German sculptor, who took up social work after being unable to square her conscience with the art market, only made work for 12 years, but it was enough for her to invent a profound, processual format. The modular arrangements of squarish steel tubes for which she’s best known resemble heating ducts: they’re pointedly industrial, art for workers, in a way; were sold at cost; and are manufacturable in unlimited editions. New ones are still being made, which seems to have been approximately in line with Posenenske’s wishes. The owners, meanwhile, were free to rearrange them however they liked, making Posenenske’s art an equalisation of authorship between artist, manufacturer and owner, as well as a merger of conceptual, minimal and performance art. That she had second thoughts about her retirement is attested to by the fact that, just before her death in 1985, aged fifty-five, she agreed in principle to an exhibition, so it’s hard to really cry foul that she’s been so widely revived – in this case, through a Jessica Morgan- and Alexis Lowrycurated retrospective that includes both her original prototypes and newly made pieces. What Posenenske may not have liked so much is the excavation of her inchoate early art, as has been seen in gallery shows lately and which may reappear in this show. But she can’t do anything about that now, and it’s surely for the better that Posenenske’s oeuvre is still operating in the world: tough and principled, shapeshifting, illuminating an alternative path.

Art & Porn at Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, through 12 January

In 1969 Denmark became the first country to make pornography legal, which simultaneously expanded what artists were able to show in galleries. That, of course, is 50 years ago now, and the anniversary is being marked by the expansive, hot-blooded, decades-spanning group exhibition Art & Porn, which debuted at ARoS in Aarhus earlier this year and now fetches up at the Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Copenhagen. Sixty-nine, as it were, is merely the midpoint of the show, which tracks back to the 1930s via Wilhelm Freddie’s surrealist sculptural bust Sex-Paralysappeal (1936) – with its female figure facially adorned with a painted penis, rope and wine glasses – and forward to the fourth-wave feminism of the present day. At its centre, addressed via works by artists including Betty Tompkins, Tom of Finland, Cindy Sherman, Marilyn Minter, Lawrence Weiner and VALIE EXPORT, is – as one might expect – the question of how the shifting rules on what is legal to depict inflect artistic practice, from Annie Sprinkle’s and Jeff Koons’s hybrids of art and porn to, more psychologically, Monica Bonvicini’s 2016 neon reading ‘no more masturbation’. (An image of which might usefully go on artists’ studio walls alongside Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s How to Work Better, 1991.)

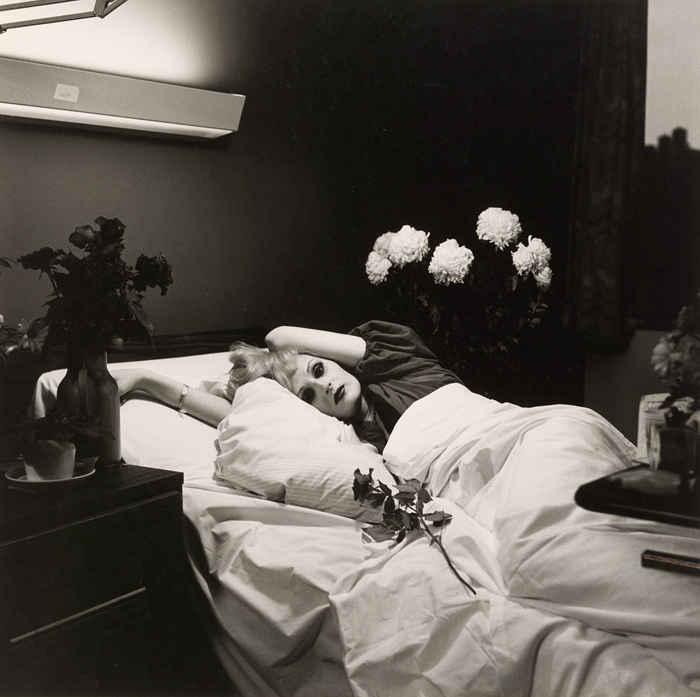

Peter Hujar at Jeu de Paume, Paris, through 19 January

Also in 1969, Peter Hujar witnessed the Stonewall riots in New York’s West Village, which have received their own share of halfcentury commemoration this year. At the time, he’d been a professional artist for two years and was little-known, despite having appeared in a Warhol film. Through the 70s, though, he cemented a reputation as a documenter, in sumptuous monochrome and rich chiaroscuro reflecting his background in commercial photography, of downtown marginal types: figures who lived on their wits and artistry and clung to their individuality, from Candy Darling to Quentin Crisp to Hujar’s lover David Wojnarowicz. In a professional life backed by the AIDS crisis and underwritten by transience – he died of AIDS-related causes in 1987 – Hujar graced his subjects with formal dignity both in life and in death. But he’s only been canonised and recognised as a great American photographer lately, the adulation peaking with Speed of Life, this retrospective, which was inaugurated in 2017 and now comes to Paris.

Patricia Kaersenhout at De Appel, Amsterdam, through 1 December

Right, enough 1969. In 1979, Judy Chicago made her canonical work The Dinner Party, a kind of stilled celebration of 39 women from antiquity to the then-present, their names inscribed on ceramic plates. Forty years later, Dutch artist/activist Patricia Kaersenhout is giving Chicago’s format a twist, an expansion. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner Too?, its title referencing the 1967 Stanley Kramer-directed comedy about interracial marriage, is an installation of over 50 glass vessels, intended as a form of ‘dining with the dead’ and honouring 38 women of colour who were also ‘heroines of resistance’. This is a work in progress, so where a 2017 iteration featured beaded table-runners, here Kaersenhout adds sculptural glassware rooted in African, Latin American and Asian tableware, while the project was led up to by a ‘stitch-in’ to make more table settings, intended as a consciousness-raising exercise and featuring Emory Douglas, former Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party. Given that Holland still has an annual, highly questionable blackface festival, Zwarte Piet, the location seems apropos.

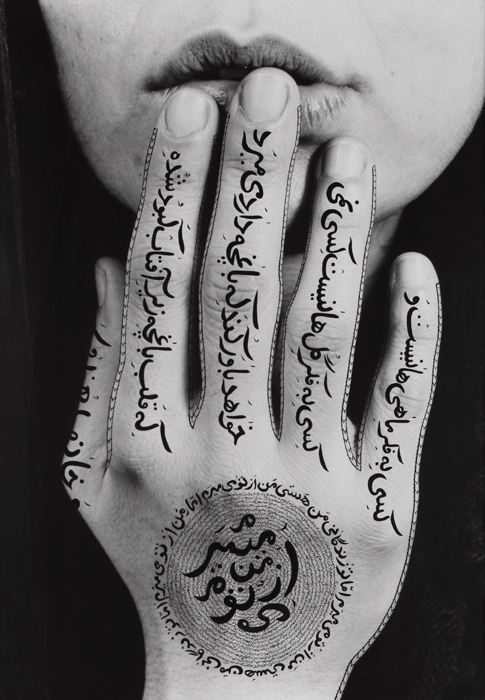

Shirin Neshat at The Broad, Los Angeles, through 16 February

Shirin Neshat has been exiled from Iran for most of her 30-year career, but the country has never been far from her mind, not least since she returned there in 1990 after 12 years away and was disturbed to find the restrictions the Islamic Revolution had wrought – as her largest exhibition yet will confirm. Across eight ‘immersive’ video installations and some 320 photographs, it tracks Neshat’s poetic, emotive engagement with displacement and identity inside and outside of her native land. Here, a viewer will move from the compound symbolism (guns, texts, veils) of her 1994 Women of Allah photographic portraits, through gender-dividing multiscreen videoworks such as Rapture (1999), where the centralised viewer cannot observe the active male and passive female protagonists at once; pivot on her 2001 collaboration with Phillip Glass, Passage, into works dealing with the post-9/11 world and the Arab Spring, and arrive at a major new work, Land of Dreams (2019), combining photography and video. Needless to say, in a country currently riven by intolerance and sexism (not to mention the omnipresent tension between the US and Iran), all of this ought to feel utterly timely.

Katinka Bock at Lafayette Anticipations, Paris, through 5 January

Displacement is also the engine of Katinka Bock’s work, though in an entirely different manner. Long resident in Paris but not showing there until now, the German sculptor has a modus operandi based, often, around transferring materials from architecture or from nature into the gallery, and on a respectful approach to sculpting that more often involves placement and bending than cutting or heavy reshaping. Her show for Lafayette Anticipations draws on the restoration of a copper-domed building in Hanover, the Anzeiger-Hochhaus, in whose basement two important German weeklies, Der Spiegel and Der Stern, were birthed. While the dome is being renewed, Bock has made off with some of the old, green-patinated copper in a suspended installation in the building’s central tower, and which summarises a movement – from basement creativity upward and outward – that Bock sees analogised in the Rem Koolhaas/OMA-designed Lafayette Anticipations building, with its hydraulic floors that literally rise towards the rooftop.

Diamond Stingily at Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, through 2 November

Katinka Bock has a great, onomatopoeic name, but it might be bettered by Diamond Stingily’s. The Chicago artist and poet (not to mention podcaster), named one of Forbes magazine’s ‘30 under 30’ in 2017, is still in her twenties and has established herself as a force in the artworld: in 2014 she announced herself with Forever in Our Hearts, an entrance-as-exit that simulated the artist’s death via funerary materials; later works, incorporating hair barrettes and beads, locked doors, baseball bats and chainlink fences and videos, homed in on racial violence. Her show late last year at Freedman Fitzpatrick in Paris, offered an array of schematic, black-headed dolls – some with two heads – and a background narrative about an unnamed place with culture impenetrable to outsiders, part of it based on the giving of, indeed, two-headed dolls. What she’ll do in Berlin is as yet unknown and unknowable, an increasingly rare quality in itself.

Haegue Yang at MoMA, New York, through Spring

Two good handles, then. And, in one of the cornier links in this column’s chequered history, Haegue Yang’s solo show at MoMA is called, indeed, Handles. Handles, for the Korean artist, are ‘points of attachment and material catalysts for movement and change’. Appropriately, then, the six sculptures here, a diversity of geometric forms sprouting the titular appendages and surrounded by son et lumière aspects, are there to be activated. Performers wheel them on casters, whence they make rattling, bell-like sounds, and the space is additionally alive with the sound of birdsong, a seemingly peaceable noise that was actually recorded in the demilitarised zone between North and South Korea during the 2018 summit. As such, underlying the idealist vibe of this work, with its sonic equanimity and visual references to twentieth-century modernism (especially Sophie Taeuber-Arp) and the mysticism of GI Gurdjieff, is both an ambient tension and a pointer towards the possibility of renewal.

From the October 2019 issue of ArtReview