If William N. Copley had never picked up a paintbrush, you might still want to read a biography of him. During the 1940s he was a California gallerist specialising in Surrealism, a friend of Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia (an apparent influence on his own later art) and Man Ray. He began exhibiting his own paintings, of which more in a moment, during the early 50s, under the name CPLY; by the mid-60s, in the wake of the second of his five divorces, he was again in entrepreneurial mode, publishing portfolios of twentieth-century artist collaborations titled, notably, SMS (for ‘Shit Must Stop’). During the 70s his own art turned from erotic to borderline pornographic, foxing what constituted his American public. He died in 1996. The Ballad of William N. Copley, a miniretrospective that nevertheless leaves out Copley’s signature painted screens, stretches from 1959 to 92.

In the earliest work, Palladium (1959–63), Copley has already established his trademark unabashed fascination with the mythic locales of the heterosexual American male (remember, five divorces), in this case a revue where lace-wrapped black women frolic together while men sit nursing wines and, distantly across a chequerboard floor, the band plays on. This work, with its compulsively symmetrical composition and faceless figures, is on the lip of what used to be called outsider art. But Copley was very much an insider, and one can’t miss the influence of Henri Matisse in the patterning and rhyming curves of the Western barroom scene Natchez Nan Watched Derringer Dan (1966), with its two behatted men playing poker while a woman prowls around them, a painting of a female nude behind them rendered in the same sophistication-meets-slapstick style.

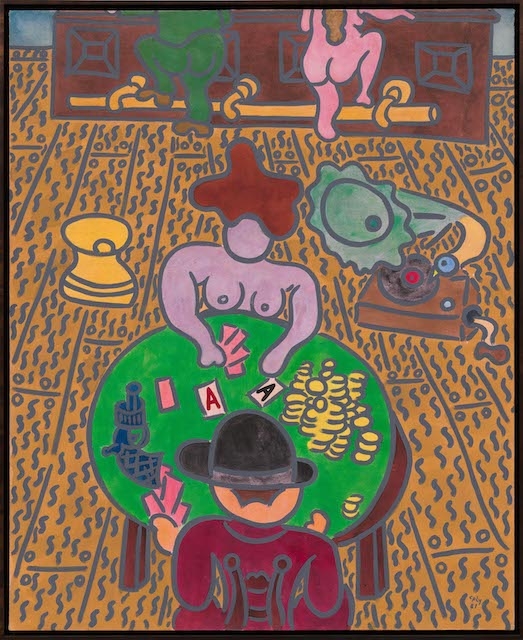

The core of the show is a roomful – a suite really – of works from this period, full of tipsy cavorting and gunplay, appended with self-explanatory titles like A bunch of us boys were whooping it up in the Malamute Saloon (1966). They feel steeped in cinematic male fantasies of sex and violence, thankfully leavened by humour, gendered self-mockery, a general sense of knowing oafishness. By 1981’s Card Players, things are bawdier. A clothed man plays cards with a naked woman – shades of the famous photo of Duchamp playing chess with Eve Babitz – while two other nudes prop up the bar. Sardonic works like Feel Like a Hundred Bucks (1986), a painting of a ripped-up banknote with an oval mirror in its centre, don’t recall anyone and stand as out-of-time Pop.

The show’s strangest and most diverting work might be Saturday Night at the Movies (1985), an interlocking mix of depictions of men’s shirts and trousers, bits of city architecture, a horned red-eyed man and myriad miniature half-naked figures scrambling about, as if escaped from one of Copley’s bars. (The gramophones that often feature in his saloon scenes reappear here.) There are touches of Öyvind Fahlstrom and Hariton Pushwagner in this work, and a frisson of consumerist critique, but the painting mostly fascinates because of its recalcitrant opacity. Much else on display boils American culture down to a vast, rambunctious, perpetually humming machinery of desire, one that might get you shot by your wife, poisoned by your husband or shitfaced in the whorehouse – all those scenarios play out here – but which was approximately as true during the 1960s as it was in the Wild West. Because Copley never really rendered his own time but filtered Americana through French modernist aesthetics and cartoons, his work isn’t pinned to the moment of its making. It likely looked brazenly askew back then; today, in an age of identitarian art where the hangups of straight white males are rightly being downgraded, it does so again.

The Ballad of William N. Copley, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 17 January – 7 March 2020

From the March 2020 issue of ArtReview