Hey art fans! Who do you love most? If art is always presented as super-serious by those who run its machine, it’s always good to see that ordinary people – which ArtReview is on the side of – tend to ignore the silly polonecked curators and head straight off to ’gram a Kusama infinity room. That’s fandom – a bit embarrassing to the powerful, easily manipulated by commercial culture, but eventually an expression of what people value through their enthusiasm or, as one contributor to Fandom as Methodology (Goldsmiths Press, £28) puts it, love. According to its editors, treating fandom as a serious critical approach allows ‘for excessive attachements to cultural objects that would otherwise be derided or minimised’, affirming a ‘sense of self or community that may not be endorsed in mainstream culture’. The book’s essays lean towards feminist and queer perspectives, but the attention to artist-as-fan, fanfiction cultures and ‘fan-scholars’ bubbles with the engaging, if awkward energy of academics trying to incorporate the guileless enthusiasm of the genre into the look-over-your- shoulder solemnity of academic writing.

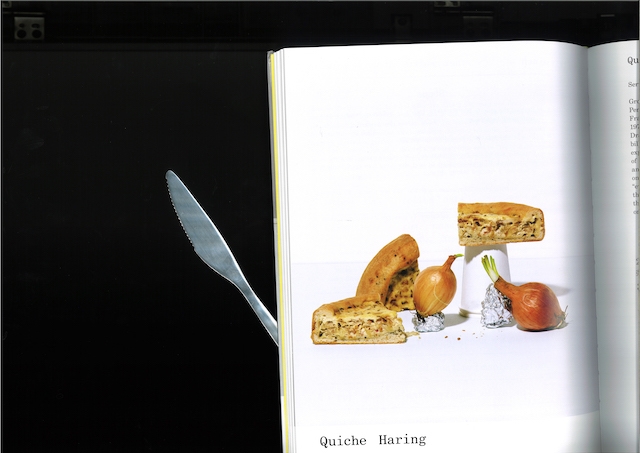

As discussions of fan-fiction highlight, appropriating and remaking the object of one’s obsession can be a subversive act. So Esther Choi’s Le Corbuffet (Prestel, £29.99) works on several levels, starting out as a collection of recipes whose titles are excruciating puns on the names of famous artists, writers, designers, musicians and architects – Quiche Haring, Mies Van der Roe Dip, Rosalind Sauerkrauss, you get the idea. Accompanied by some brilliantly absurd food photography, some sound like they might actually taste good; but Le Corbuffet is more a celebration of how an arbitrary concept spawns unthought-of culinary possibilties; though ArtReview feels a bit full after a plate of Lawrence Weiners, followed by Vladimir Tarte Tatlin. Seriousness and authority, then, can be torpedoed by an artist’s deployment of supposedly ‘humble’ or ‘domestic’ genres and techniques – an issue that runs through Grayson Perry: The Pre-Therapy Years (Thames & Hudson, £19.95). Perry is today a fan-followed art celebrity, but the Turner Prize-winning, self-styled ‘transvestite potter’ found fame late. This definitely ‘fan-scholar’ book offers up thoughtful accounts of Perry’s earlier life in the gay, postpunk and New Romantic bohemianism of 1980s London, while charting Perry’s enthusiastic immersion in ‘naffness’, English suburbanism and pottery as the greatest a.ronts to sophisticated artworld tastes. Excavating the early careers of celebrated artists is a familiar aspect of artworld preoccupations and there’s inevitably a market for what, in music-fan terms, would be ‘B-sides and rarities’. Sigmar Polke – Objects: Real and Imagined (Michael Werner Gallery, not for sale) catalogues a recent show of mostly 1960s works on paper by the German iconoclast, in which Polke first essays his impish, satirical form of ‘Capitalist Realism’ (the movement Polke formed alongside Gerhard Richter) – sketches for sculptures such as standing trellises connected by potatoes, ‘fountains’ made from beer mats and other wry comments on Modernist hubris and (West) German postwar consumerism. That the book itself is a limited edition makes it one for completists.

Polke may have lampooned good taste with references to pop culture, but in millenial neoliberal culture, good taste has been reinvented as the sophisticated attention of contemporary art- and design-appreciation. Susan Finlay’s funny, bleak and sharply observed novel Objektophilia (Ma Bibliothèque, £12), about a London-based design critic and her architect historian partner, immerses us in the obsessive preoccupation with objects – artworks, buildings, fast food, luxury goods, ‘niche’ design – that besets those who make a living from the culture industry. As the protagonist moves from lecture hall to design award presentations and magazine assignment, and from Brutalist architecture via Memphis design classics to Vienna’s coffee houses and the toiletries in luxury hotels, the critic’s attention to the look of things sensitises us to the anxiety of not having something to say about stylish stuff – part-erotic fixation, part cultural disease.

Obsessing over things, though, can also be restorative, particularly in the very strange vision of ordinary life assembled in experimental filmmaker and broadcaster William English’s Perfect Binding: Made in Leicester (William English Editions, £20). English’s deeply personal excavation of life in humdrum 1960s Leicester is achieved through interviews with family and friends, anchored by a sense of care for the memory of the lost things and places of provincial 1960s – Beatniks, Mod fashion and music, off-prescription recreational drugs, middleclass alcoholism, shortlived basement clubs and draughty coffee bars.

So ArtReview is keen on the giddy enthusiasm of the fan, but sometimes gets embarrassed when it has to join in. Thus The Obama Portraits (Princeton University Press, £20) which marks the commissioning of portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama, by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald respectively, does get swept up in the hype (it’s the Obamas, after all) with hyperbole to match; ArtReview isn’t totally sure that the unveiling of the former First Lady’s portrait ‘will be remembered as a turning point in the history of portraiture’. But while the essays illuminate the history of presidential portraits, and the layered references that Wiley and Sherald build into their portraits, for many Americans, the Obama portraits signalled how much Obama symbolised beyond the status of his office. Fandom is only partly about the object of adulation; it’s really about the unfulfilled hopes and desires of those doing the adulating.

From the March 2020 issue of ArtReview