There’s something quite compelling in obsessive repetition, the way, say, French composer Erik Satie insisted on repeating musical motifs over and over, or 840 times in the case of Vexations (1893–94), as if on a mystical quest. Though here Satie was striving to test the virtues of ‘boredom’ in music, Rachel Whiteread, whose whole oeuvre consists of variations on a single approach, seems on a quest to capture the essence of memory. Her repetitive process is made bluntly apparent in this retrospective, which, housed in one large room, offers a panoramic view of her oeuvre. Throughout her 30-year career, the British artist has been casting – in concrete and plaster for the most part, as well as using a range of other materials including resins, glass, rubber and wax – the ‘negative spaces’ around domestic objects and structures (from toilet paper rolls to bathtubs to entire houses) to reveal their imperfect surfaces and undersides, paradoxically preserving their presence by making their absence tangible. As these empty spaces materialise, they become lasting tributes not only to objects and places, but also to memory itself – giving shape to its abstract and fleeting nature.

The two aisles formed by the plaster-cast rows of cabinets in Untitled (Book Corridors), 1997–8) evoke library shelves stacked with books, but take a closer look and you’ll realise these are not casts of bookshelves, but rather of the spaces between them, revealing the books’ pages rather than their spines. The same goes for the haptic Torso series (1991–99), which renders the emptiness inside a hot-water bottle in plaster, rubber, resin, wax and concrete. Some of the resulting objects actually look their part (the cast of a cardboard box’s interior ultimately looks like its original), but the most intriguing ones differ enough from their model to keep things interesting. The experience of looking at Untitled (Stairs) (2001), for instance, a freestanding concrete sculpture of two flights of stairs facing each other, is something comparable to trying to figure out whether the edges of a cube drawn on paper are projecting out from or receding into the page: you’re never quite able to make out what the ‘positive’ version of the stairs would look like. But perhaps that’s exactly the point: the sculpture is not so much a reference to a specific staircase as it is a means to speaking about the people who used it, and capturing something of the sense of a place.

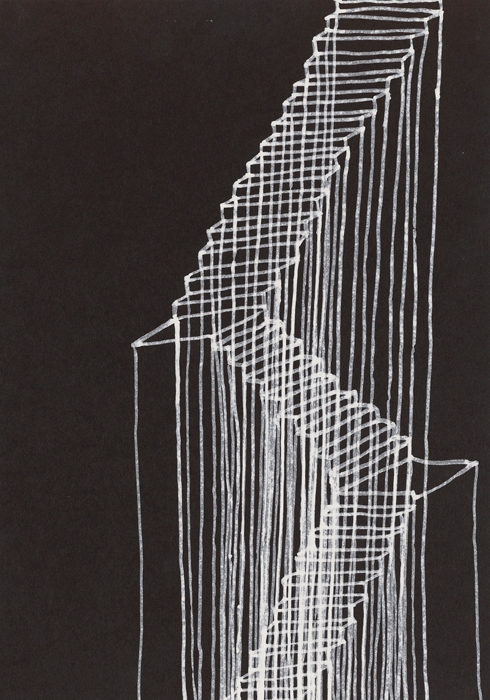

A surprising addition here is a selection of the artist’s works on paper. Rarely shown, these denote Whiteread’s poetic inclination towards abstraction: a painted, semifolded cardboard work, reminiscent of Richard Tuttle’s compositions, looks like a template for an unrealisable structure; details of a chevron-motif floorboard, painted on graph paper, suggest an Agnes Martin-like grid; the perspective of a zigzagging staircase, outlined in correction fluid on black paper, collapses under the repetition of vertical lines, seemingly dripping from each angle of its steps. These works offer a refreshing counterpoint to an exhibition that risks running out of steam. Whiteread’s recent series, including almost-pristine translucent-resin casts of doors and window frames as well as shed facades in papier-mâché, seem to lack the poignant presence of so much of the other work here. Repetition, it seems, can only run for so long before it starts to lose any virtue.

Rachel Whiteread ran from 12 September 2017 – 21 January 2018 at Tate Britain. and travels to Belvedere 21, Vienna, where it’s on view through 29 July 2018.

From the March 2018 issue of ArtReview