Bruce Conner, Bellas Artes Projects, Manila, 24 February – 24 May

Affiliated with California’s neosurrealist assemblage scene from the 1950s onwards but a mystic-minded outrider even there, Bruce Conner was determinedly elusive in life. He announced his own death twice, officially renounced art in 1999 and earlier operated under aliases including Emily Feather, BOMBHEAD and the Dennis Hopper One Man Show. Conner was also, as his recent resurrection within the artworld reflects, something of a visionary. He was a mocker of authorship who pseudonymously exhibited nineteenth-century engravings; his 1966 film Breakaway, featuring hyperactive dancing by Toni Basil, is considered the first music video; his 1975 Crossroads, 37 minutes of slow-motion footage (soundtracked in part by Terry Riley) of the 1946 nuclear test at Bikini Atoll, remains bleakly mesmeric and is hardly his only film made from purloined imagery. A transformative out-of-body experience Conner had aged eleven gives its title to Bruce Conner: Out of Body, which focuses on his films but also includes photographs and works on paper, and which, as the artist might well have liked, you’ll venture to the Philippines to see.

Lee Lozano, The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, 10 March – 3 June

Another adept of wilful difficulty, Lee Lozano is best known for quitting the artworld – she began Dropout Piece (1972) a year after she’d stopped speaking to women, also in the name of art – and staying quit until her death in the same year Conner retired. But she was a supremely incisive and shapeshifting figure while remaining ‘in’, from her fluidly sexualised semiabstract canvases of the early 1960s through the more familiar, greyscale ‘Tool’ images that followed, with their overtones of gender inequality (and their origins in Lozano’s move to a studio ringed by industrial workshops). Her subsequent handwritten, conceptual instruction pieces, meanwhile, recorded bold experiments with drugs and unusual rules for social life. The show at Fruitmarket Gallery, anchored by four huge mid-60s paintings, covers the key phases of Lozano’s inquiry into containment and freedom, and brings to light previously unseen materials from the archives.

Hardeep Pandhal, Cubitt, London, through 8 April

Rising star Hardeep Pandhal has cornered the market in combining animation-driven, rap-soundtracked videos with presentations of hand-knitted woollen jumpers. The backstory to these is cultural dislocation: Birmingham-born, Pandhal is a British Sikh who doesn’t speak the same language as his Punjabi mother, and making the clothes creates a bond. This is also work that balances a traditionally nonmasculine activity with the embroidered faces of American rap stars, and a darkly satirical approach to the relationship between structural racism and misogyny also underpins Pandhal’s animations. So, too, do heterodox sources: for example, the new work Pool Party Pilot Episode (2018, showing simultaneously in the New Museum Triennial) explores male fears of their environment, drawing on Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 novel Herland, involving an all-women society where conception happens via parthenogenesis, and Elaine Morgan’s aquatic ape hypothesis, which recasts evolutionary theory by focusing on the female body.

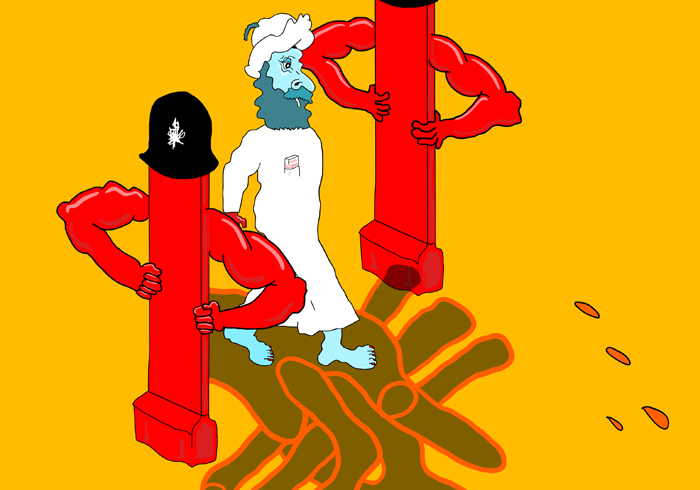

Vittorio Brodmann, Freedman Fitzpatrick, Los Angeles, 4 March – 21 April

Vittorio Brodmann’s last gallery exhibition was titled Legs All Water, which figures: the Swiss-born painter builds his chromatic, flowing, instinctively composed figurations on structural liquidity. In his older canvases, faces and bodies dissolve into each other, social anxiety and claustrophobia and pleasure implicitly melding; more recently, Brodmann has liquefied his aesthetic further. Contours melt as the artist picks up acrylic, gouache and charcoal rather than oils, his figures becoming misty hints and colours phasing into watery pastel that should suit this latest show’s Los Angeles context nicely. Brodmann’s art, which fuses soft lyrical abstraction, Surrealism and echoes of cartoons, perhaps ought to be anachronistic in an increasingly dematerialised reality. But, via old-school media, he catches something of the texture of our moment – the sense of entering, or even being outside of, a perpetual flow of fragmentary information – without being wearyingly doctrinaire about it.

Mathilde Rosier, Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan, 14 March – 5 May

Shuttling between painting, set design-like sculpture, video and performative elements, Mathilde Rosier nevertheless regularly stalks a line between reality and warped fairytales. In the French artist’s light-touch paintings, humans merge with animals, or sprout abstract protuberances. Over the last couple of decades Rosier has built more angles on her oeuvre, though as if while forever inhabiting another time: resembling childhood, but conveying no safe return to its certainties. In Rosier’s last Milan show, dancers spun both in drawings and on video; painted heads became conches. From what we’ve seen, in the current one the emphasis appears again on painting, with balletic legs en pointe emerging unnervingly from skirts-cum-shells and the consistency of the artist’s concerns signalling ongoing private compulsion.

Michael Raedecker, Grimm, Amsterdam, 10 March – 14 April

Another painter who refuses to just paint, Michael Raedecker has salient reasons: in a recent interview he pointed out that his trademark use of embroidery places him right up against the canvas, whereas painting keeps the artist a brush’s length away. The distinction might seem odd were it not for how deeply the Dutch painter, long since resettled in London, inhabits his work: his motifs of ominous-looking houses and interiors, often in moody hues of blue and grey, always seem to arise from psychological unsettlement that Raedecker is working out on canvas. If he never fully knows what he’s returning to, nor can we; what’s clear, though, is that he’s endlessly removed from closure with his work in formal terms, balancing comforting familiarity with some unexpected new twist (spacious, near-abstract compositional reduction; portraiture; a combinatory approach to his motifs). Even in coming back to the Netherlands for this show, you suspect Raedecker won’t feel to have reached home.

1st Lahore Biennale, 18–31 March

Pakistan’s first major presentation of contemporary art, the 1st Lahore Biennale, has faced a rocky road to realisation. After some pre-events were launched in 2016 and an open call for submissions was announced in early 2017, later last year the inaugural artistic director, Rashid Rana, announced that he was stepping down after differences of opinion with the biennale’s foundation. By December, though, the event was back on the rails, with noted Pakistani academics, novelists and architects joining the advisory committee. At the time of writing, it’s still on, albeit with no artist list announced and the organisation still looking to hire ‘designers’. Fingers crossed, as the biennale’s goal – establishing Pakistan as a known site of contemporary art production – is perhaps unlikely to go ahead swiftly otherwise.

Carissa Rodriguez, Sculpture Center, New York, through 2 April

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a multitasking artist who directed the collectively authored fictional gallery Reena Spaulings, Carissa Rodriguez dwells on infrastructural concerns: the mechanics of art’s distribution, presentation, valuation. Opposed to creating ‘signature objects’, she tends to favour antiauratic remove and veer pointedly about, previously exhibiting photos of her own work in private collections and a project about how the ostensible transformation of the Bay Area relates to technology and creativity. In Rodriguez’s first New York museum show, and similarly to how a 2013 exhibition took its cues from La Collectionneuse, a 1967 film related to art by Éric Rohmer, her new work The Maid takes a cinematic approach to sculpture, considering ‘the conditional relationships between artist, artwork, and third-party agents (institution, caregiver, surrogate) in familial terms’: the evolved social dynamics of the artworld, and the laws that underpin them.

T.J. Wilcox, VNH Gallery, Paris, 15 March – 28 April

We like to check in on T.J. Wilcox every few years, because he’s usually doing something unexpected, even while favouring 8mm and 16mm film. He’s made, for example, tender and poetic collagelike studies of historical figures and a 360-degree panorama of the view from his Manhattan studio (In the Air, 2013) relating to nineteenth-century ‘cinema in the round’ presentations. His last London show, at Sadie Coles HQ, suggested his retrospective gaze was turning somewhat on himself, and on his plush connections: it included a film from 1998 concerning the English aesthete Stephen Tennant (as considered by his great-niece, model Stella Tennant), plus filmic portraits of fabled London chef Fergus Henderson and New York jeweller John Reinhold, the former filmed in Scotland, the latter built on dozens of hours of telephone conversations and interjections by Debbie Harry and Marc Jacobs. After presenting a New Yorker in London, a Londoner in New York would make sense.

Judith Hopf, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, through 15 April

Five years ago Judith Hopf cast a small flock of concrete sheep from home-moving boxes, completing them with sticklike legs and cartoonish faces. The unspoken word hanging over Flock of Sheep (2013), perhaps inevitably, was ‘sheeple’, given its precising of human acquiescence to relocating wherever, suckered by neoliberalism’s lauding of mobility. As such and also for their downbeat humour and empathy, Hopf’s blocky ruminants exemplify the Karlsruhe-born artist’s practice, which since the 1990s has tracked contemporary society’s homogenising demands on body and soul. This institutional show in her adopted city, Berlin, leans on her pivotal series of perverse red-brick works, cemented and then sanded into the shape of hands, feet, basketballs, suitcases, robots and more – though these evocations of pliant malleability here occupy, we’re told, ‘an intermediary position that fluctuates between sculpture and (exhibition) architecture’. Expect, too, some of Hopf’s laptop sculptures – angular, recumbent, semifigurative geometric sculptures from whose midpoint a screenlike shape pokes up, body and machine fused – plus a new film and a commission for the KW’s facade. We’d say go along; but hey, you’re not sheep.

From the March 2018 issue of ArtReview