The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, 28 July – 30 September

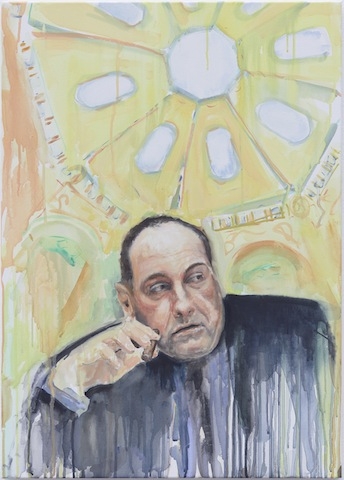

Among the 47 works in Calling on Gravity, one notable for its title alone is the liquescent oil painting Tony Soprano at the Kunsthistorisches Museum (2017), in which the complicated fictional mobster looks pensive, smoking a cigar, against a lemon-yellow rendering of the Vienna museum’s domed ceiling. That Soprano doesn’t belong there is partly the point; Nolan, she’s said, has issues with how museums latently enforce hierarchies, including the way they coerce us to look up, respectfully. It makes sense, then, that her well-stocked yet spacious assembly here of sculptures, drawings, paintings, photographs and rugs, dating from 2012 to 2017, feels like a minimuseum, but also one that superficially makes very little sense.

Four ‘characters’ appearing in her light-touch, watery oil paintings might guide you through it: the aforementioned Soprano, the theologian/cosmologist Giordano Bruno, the philosopher/activist Simone Weil and the artist Paul Thek, each of whom was a strange, category-scrambling mix of the mystical and the rational. (Soprano murders people, but he has a philosophy too, scrawled on another painting: ‘You are born to this shit, you are what you are’.) Each figure, too, appears against a contradictory backdrop: there’s a lot of luminous modernist abstraction in Nolan’s daubing, which fits none of the figures. Alongside these, you find things that should be elevated brought down to earth: a sequence of crisply fabricated chandelierlike sculptures, dropped to the floor or tipped on their side, sometimes draped with cloths whose colours suggest the play of light but actually blocklight. Various photographs, snapped in museums and hung deliberately low, depict the sculpted feet of saints, which Nolan had noticed are always off the ground (hovering or lying down, their soles visible), as if anticipating leaving earth for heaven; while various others, taken outside museums, are resolutely earthy: pigeons puttering, feet on pavement.

Meanwhile there are all manner of nooks and alcoves that present miniature upendings. Clinging to one secluded wall is “What kind of dust is it?” (2017), a line of coppery lumps in compressed insulation foam, apparently magnified dust particles; a rainbow-bright coloured-pencil drawing near the entrance, Doryphoros in Glory (2016), records Nolan’s sedulous, irreverent attention to the ass of a Greek sculpture depicting the eponymous warrior. A geometric floor-based sculpture, Narcissus’ pool (for SMcK) (2017), whose title suggests it might have something to do with the late artist Stephen McKenna (with whose estate Nolan shares a gallery) does suggest rippling water in its nested format of geometrical shapes, but also replays the authoritative effect of institutions: we get the association because the title pushes us that way.

Mostly, though, what Nolan achieves is a kind of suspension, one that ends up being a gift, speaking to and, for a moment, symbolically undoing authority and class structures. Associations cancel themselves out: for every upward movement here there’s a downward one, for everything old there’s something newer, and the show offers no logical route through itself; it’s an elegant sprawl in which you can’t even hold onto medium-specificity. The outcome is a kind of mobilised reverie in which you don’t feel the force of instruction, but rather give yourself up to blissful, untethered drift, and forget the paradox that someone has orchestrated this for you.

From the December 2017 issue of ArtReview