‘The exhibition green postcard considers the eponymous John Baldessari short film (1971) as a meme painting in today’s era of the meme,’ starts the exhibition text, somewhat gnomically. And since the Baldessari work isn’t here, who knows what that means? That quibble aside, green postcard clearly does want us to consider something of the historical process of technical obsolescence – painting made obsolete by the advent of photography, then photography made obsolete by the advent of digital imagery – and where that might leave the value of the physical artwork, and its relationship to images. And like Baldessari’s absent work, it’s the absence of images that looms large.

That this doesn’t end up as another slightly defensive show of nondigital artworks seeking to recuperate materiality from the depredations of the all-consuming digital is credit to its curator, New York poet and critic Max Henry, who stages works by nine artists with a theatrical precision that mutually reinforces such apparently slight and sullen wall-based works. Fronting the show with Untitled, a remarkable 1986 film by Mark Dion and Jason Simon, is an inspired choice; Untitled mimics po-faced art documentaries, but it’s really a satirical prod at the art restoration business, with a young Dion lifting the lid on the scandalous practices of unscrupulous art dealers and the painting restorers they employ to recut, cannibalise and repaint deteriorating antique paintings.

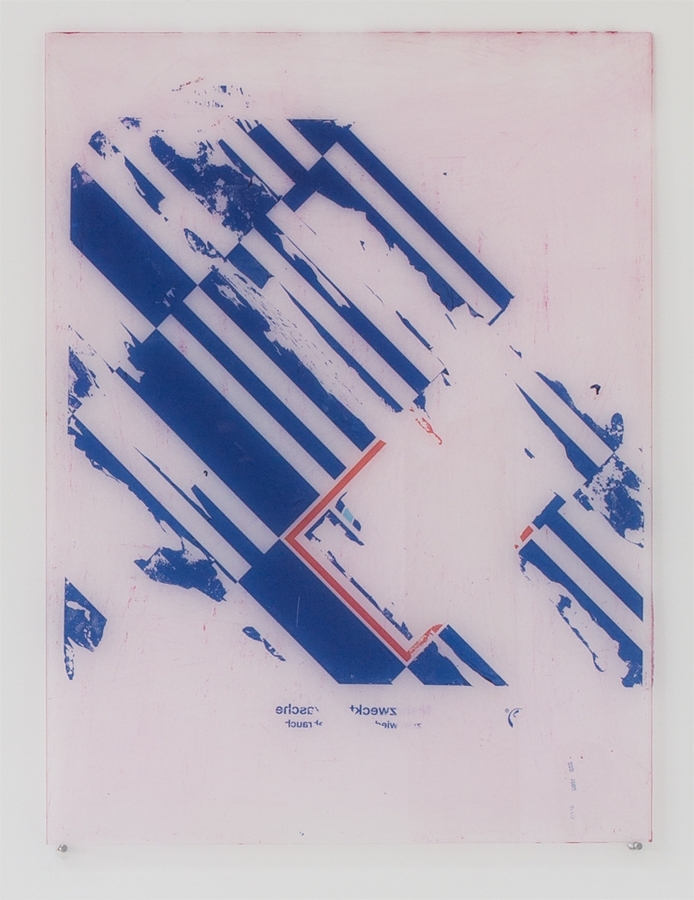

Untitled (or Artful History: A Restoration Comedy, as the film is in fact titled) has an early postmodern preoccupation with the truth and falsehood of images, and the confidence tricks of historical provenance, but its particular effect here is to sensitise us to the surface of painting, as something that is no longer the carrier of an image but is instead a crumbling skin slowly fading into cultural insignificance and archaeological decay. Seen through the lens of Untitled, green postcard becomes a meditation on the ruin, or redemption, of representation, somewhere between the surface of painting and photography. There are plentiful gestures of negation here, and exotic chemical techniques: Mandla Reuter’s two large-vitrined sheets of creased canvas serve as the mounts for a dense black surface of lightsensitive diazotype; Michael Part’s murky glass panels are coated in glittering, oily blue-black, apparently ‘silver and selenium toning’ – photographic chemicals stripped of their purpose. Rey Akdogan’s scuffed-up Plexiglas panels bear the traces of a contact-transferred motif, though legibility is less important than the evidence of such a mechanical process. Meanwhile Julia Haller and Anita Leisz’s white melamine panels are host to inset black-framed surfaces on which trail metallic filigrees, representing nothing much.

These works share a theme of withdrawal from the surface-scene where the image should be, back into the raw materials of canvas, photochemistry or reprographics that normally produce the image. Beautifully insular, they trade in their obsolescence for a dandyish selfsufficiency. So what looks like a small, monochrome canvas by John Henderson (Type, 2014) is covered with blank brushstrokes that appear crazed with age. It turns out to be an electrotype – a facsimile cast by copper electroplating, a perfect copy of a surface, not an image. Elsewhere Pieter Vermeersch’s painting Untitled (2011) offers a trompe l’oeil chromatic gradation that appears to relate to the distribution of light in the surrounding space, but is sheer simulation. If there are no images here, these are nevertheless works that continue to demand something of representation – that it still might hold the possibility of an authentic, indexical relation to the reality of things.

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue.