Today’s artworld, in which art and mainstream culture are in relentless gaudy interchange, isn’t so new. Thomas Crow, now in his late sixties, has lived amid such fluxions for decades, and traced them back further: his Modern Art and the Common Culture (1998), for example, is one broad tapestry of relativist crossovers spanning mid-nineteenth-century Paris to the time of its writing. The American art historian’s most recent book takes the antihierarchical movement par excellence and inflates it so that, rather than being a 1960s phenomenon, Pop fills two-thirds of the last century. In discussing its roots in the 1930s induction of American folk-culture into American museums, its containing of ostensibly non-Pop figures such as Billy Al Bengston and designers such as Milton Glaser and Rick Griffin, and its delayed renascence in Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst et al, though, Crow has a larger agenda. He wants to tell the story of how avant-garde art took root in America, leveraging ‘folkloric authenticity’ in order to legitimate itself.

Crow’s method is to set a host of satellites in orbit, each chapter taking a specific focus while nevertheless segueing into the next. He explores how, during the 1930s and 40s, folk culture was temporarily imported into museums like MoMA as a way of shoring up political consensus. He compares the recombinant pre-Pop of Jasper Johns and the activities of the great, wayward ethnologist and anthologist Harry Smith, noting that Johns’s motifs of flags and targets were found also in earlier folk-art reliefs and sculptures. He forensically reconstructs Roy Lichtenstein’s development from Picasso wannabe into young Pop master, complete with Mickey Mouse-related iconographic detective work. He nests Andy Warhol’s and James Rosenquist’s career shifts in and out of advertising within larger narratives of the ‘creative revolution’ in 1960s advertising and the artworld’s shifting terms. Testing the edges of the Pop continuum leads Crow inevitably to Los Angeles and London: to wave-riders and hot-rodders in the former and the Independent Group in the latter, via consideration of changes in the education systems of both countries.

Crow tells the story of how avant-garde art took root in America, leveraging ‘folkloric authenticity’ in order to legitimate itself

Crow, at points, is pretty much waving his library pass and his press pass in the air. He’s ostentatiously at ease with recounting signal changes in surfboard technology and Bengston’s transmuting of a surfboard logo into luminous abstraction; in several consecutive sections, he brings comics, graphic posters and rock album art under Pop’s rubric, showing a sociological grasp of their interrelation. By the epilogue, which skids through the 1980s and 90s, Pop is a flickering ghost, appearing here in Raymond Pettibon’s album covers, there in Marcus Harvey’s Myra (1995). The endpoint is Hirst, who Crow appears to grudgingly admire for having shifted the terms of a relationship between art and the mass media – turning his celebrity into art – that American artists see in more defeatist, immutable terms.

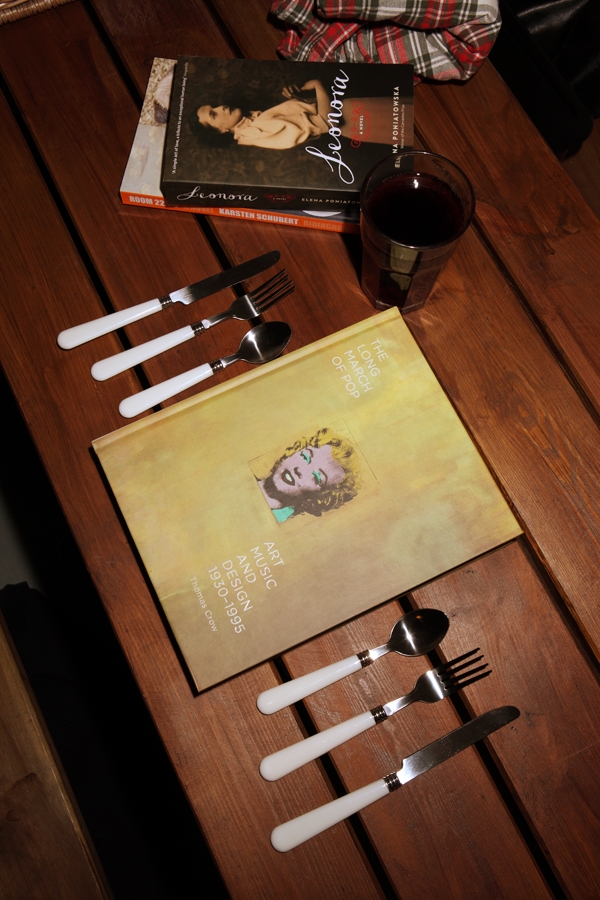

Make no mistake, though, this is an American narrative, since Hirst’s art is seen as owing much to US precursors. Its cutoff date means that Takashi Murakami – who one might logically see as a continuation of Pop – doesn’t get a mention. In its grand approach to American culture, this book seems, slightly weirdly, to be Crow’s attempt to turn himself into music and cultural critic Greil Marcus. Structurally, The Long March of Pop is effectively Marcus’s Invisible Republic (1997) – which took Bob Dylan’s 1960s music and traced it, again via Harry Smith, back to the 1920s and 30s – crossed with his earlier Lipstick Traces (1989), which similarly expanded punk into a century-spanning history of negation and dissent. Crow mentions Marcus early on, and says he’s not going to try and tread on his territory. And indeed he doesn’t, precisely; he just does something parallel – minus the hog-riding-professor verve – since you don’t hear Dylan or the Sex Pistols the same way after those aforementioned books and you won’t see Pop the same way after The Long March of Pop. As seen here, it’s murkier, richer, more ragged, and evidently the art that a nation congenitally suspicious of the highfalutin was destined to create.

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue.