the man who disappeared (amerika) at Neugerriemschneider, Berlin reanimates Majewski’s great-great-granduncle and his milieu of the American West

Plenty of painters have recently used generative AI programs as compositional aids or agents of chance. Meanwhile, numerous tech-savvy commentators have noted that such services, in drawing on and recombining a vast data pool of existing art by human makers without permission or recompense, constitute part of today’s digital colonialism, the goldrush for data. Artists have been slow to dovetail these phenomena, perhaps lest they appear to be colonisers themselves. But in the paintings, video and documentary materials that comprise the man who disappeared (amerika), Antje Majewski boldly goes there.

Following a residency at the Villa Aurora in Los Angeles (which might have prompted her to consider her own relationship to the American West), the German artist uncovered letters – included here – from her great-great-great granduncle. This man, an artist called Georg Pflugradt, migrated from Leipzig in the mid-nineteenth century, fetching up first in New York and then making the arduous crossing to California detailed in his epistles. On a centrally positioned monitor in the main space is A Journey in Reverse (all works 2023), a video that inverts Pflugradt’s journey, a symbolic undoing perhaps. Majewski’s ancestor journeyed west in the hopeful first year of the California gold rush (1848–55): though his letters focus on hunger, thirst and rough trails, and end with him warning future prospectors away unless they like fighting, it’s hard to imagine he went there to surf. While reading his words aloud, Majewski mordantly films places on the way from the West Coast to the East, showing what crisscrossing America looks like today: fenced-up cattle, ugly big-box stores, nostalgic monuments to pioneer-era writers like Willa Cather.

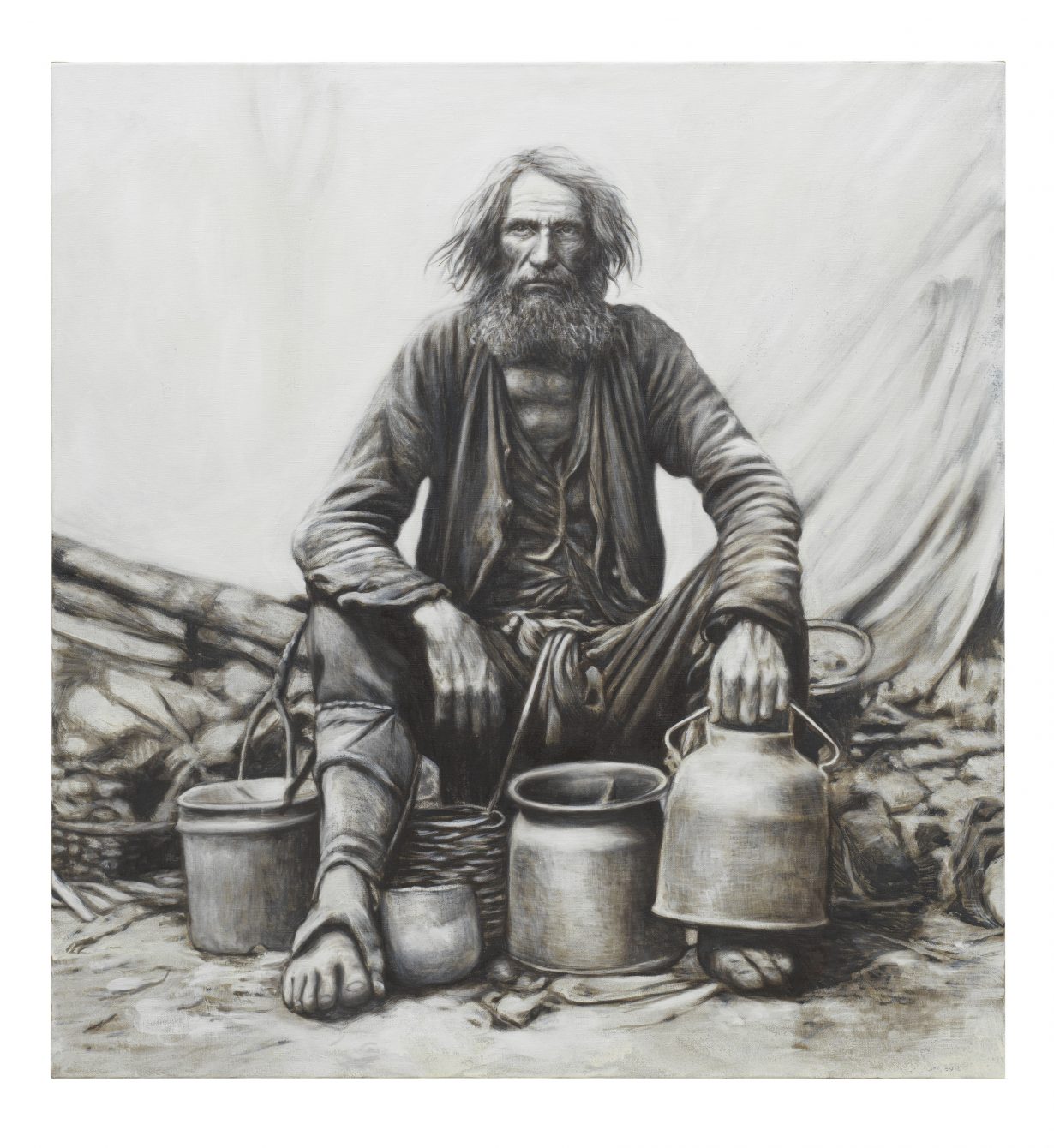

Alongside this, and before the show transitions into ancillary displays of maps of the United States, books on the history of the American West and sketchbooks of her watercolours, Majewski offers up six affectless, AI-assisted figurative oil paintings – landscapes, seascapes, portraits – collectively titled Unreliable Images. These seemingly strive to reanimate Pflugradt and his milieu. The subtitles suggest AI ‘prompts’: one canvas, of a girl in a demure dress and headscarf behind whom a town nestles in a landscape, is titled Unreliable Images (1849: a painting of a young girl from a fine Mormon family, background shows historic Salt Lake City in 1849; painter is a German migrant). A portrait of a bearded, tramp-like man surrounded by cooking pots and pails – the work’s subtitle is too long to reproduce here – suggests Majewski, with help, conjuring her worn-out forebear in 1850.

Pflugradt, his missives suggest, eventually did okay, setting up small businesses on the West Coast, but he’d likely hoped to strike it bigger. In using extractive tech – generating images from a digital mechanism that draws on authored images of the American West and its settlers – Majewski symbolically aligns herself with her enterprising ancestor; the painted results, somewhere between creepy and inert, are edged with self-criticality and feel like illustrative supports to the video. As demonstrations of AI’s impact on painting, they are, paradoxically, boldly weak. Majewski apparently doesn’t possess any more letters from Pflugradt, whose life – as the show’s title suggests – now constitutes glimmers in a void. Her show, then, whose title mirrors that of Franz Kafka’s incomplete novel (published 1927), is in part about gaps in knowledge, applied on a variety of scales: from family history (and German white-settler history) to who in California right now is mining and profiting from our data. Pflugradt didn’t unearth any gold; Majewski, particularly in these paintings, appears to have ensured that she didn’t either.

the man who disappeared (amerika) at Neugerriemschneider, Berlin, 27 January – 24 February