“I started to walk a lot in the world, I met many shamans – pajés, xamãs – from different peoples. And they begin to guide me, to expand my awareness to larger cosmogonic issues.”

Jaider Esbell, the Macuxi artist and activist, has died. He was a driving force in Brazil’s indigenous art movement, and ran a self-described ‘laboratory’ in Boa Vista, Brazil, which shows work by artists from multiple indigenous ethnicities and runs art and theory workshops. In the latest issue of ArtReview, Esbell talked to editor-at-large Oliver Basciano about making art inspired by Makunaimî – both a god and an ancestor – as well as his conversations and collaborations with shamans who represent different peoples, confronting the environmental and social abuse of Makuxi land in the Roraima region of Brazil. Esbell described his work as an essential “artivism”, at work with wider transcosmological forces, shaping his intricate, colourful paintings.

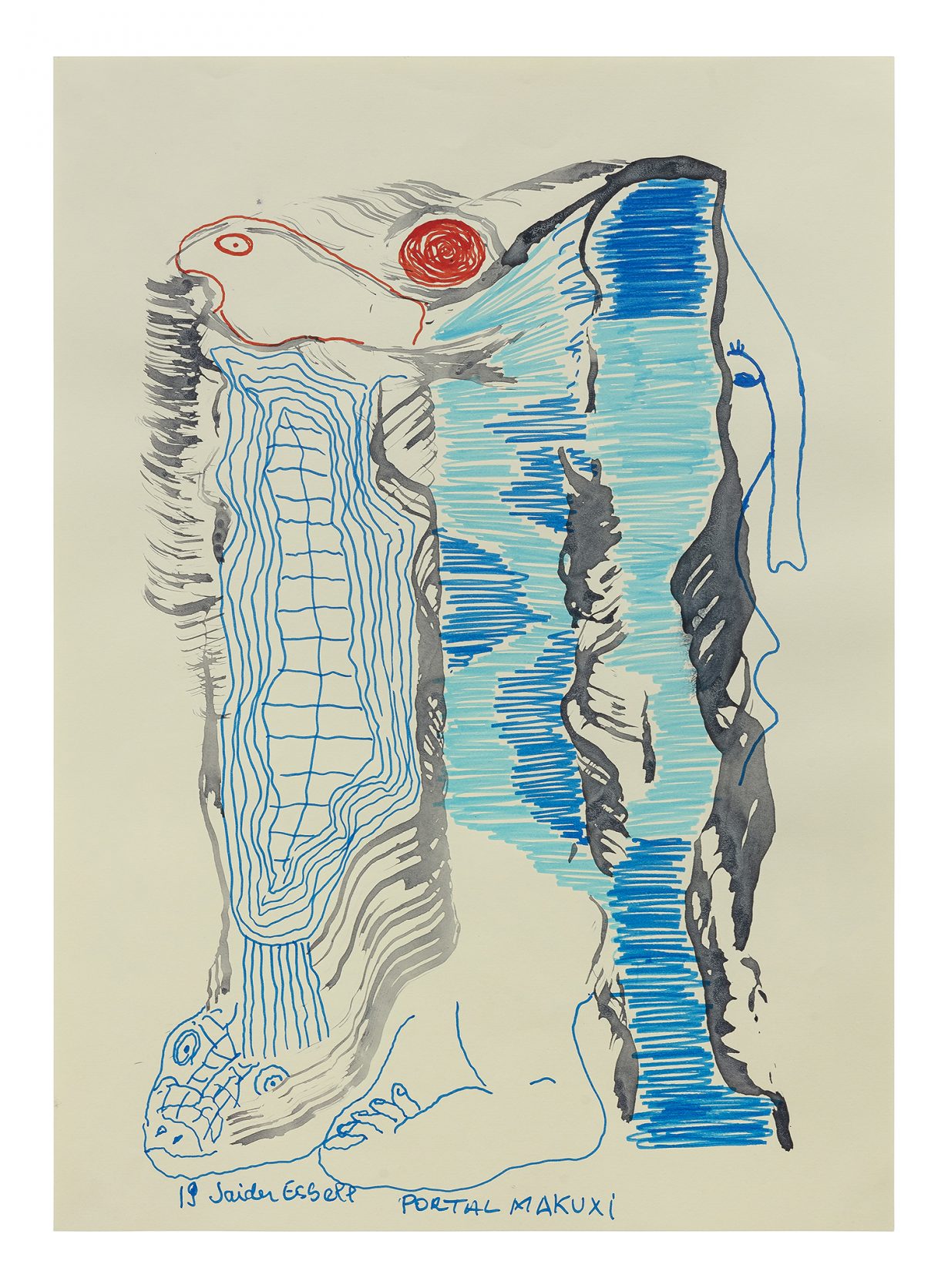

“I’ve never taken a course in art history, I’ve never taken a course in almost anything related to art, but very early on I had access to cosmology, right? Another type of art,” says Jaider Esbell. The artist is a member of the indigenous Makuxi people, whose land is occupied by Roraima, the northern state of Brazil, as well as parts of Guyana and Venezuela. “Mount Roraima is an indigenous work of art, a mythological, cosmological, and even geological work of art. Why is it a work of art? Because Makunaimî” – who the Makuxi consider both a god and an ancestor – “drew it, he made it with the axe and created that sculpture. That’s long, long before Europe existed, long before a museum existed in Europe. So we’re actually way ahead of Europe – light years.” To see that point made in his art, consider one of Esbell’s works in the recently opened Bienal de São Paulo: in Carta ao Velho Mundo (Letter to the Old World, 2021), he has drawn and written over a book of European classical art, layering it with motifs of Makuxi culture and commentary on their cause.

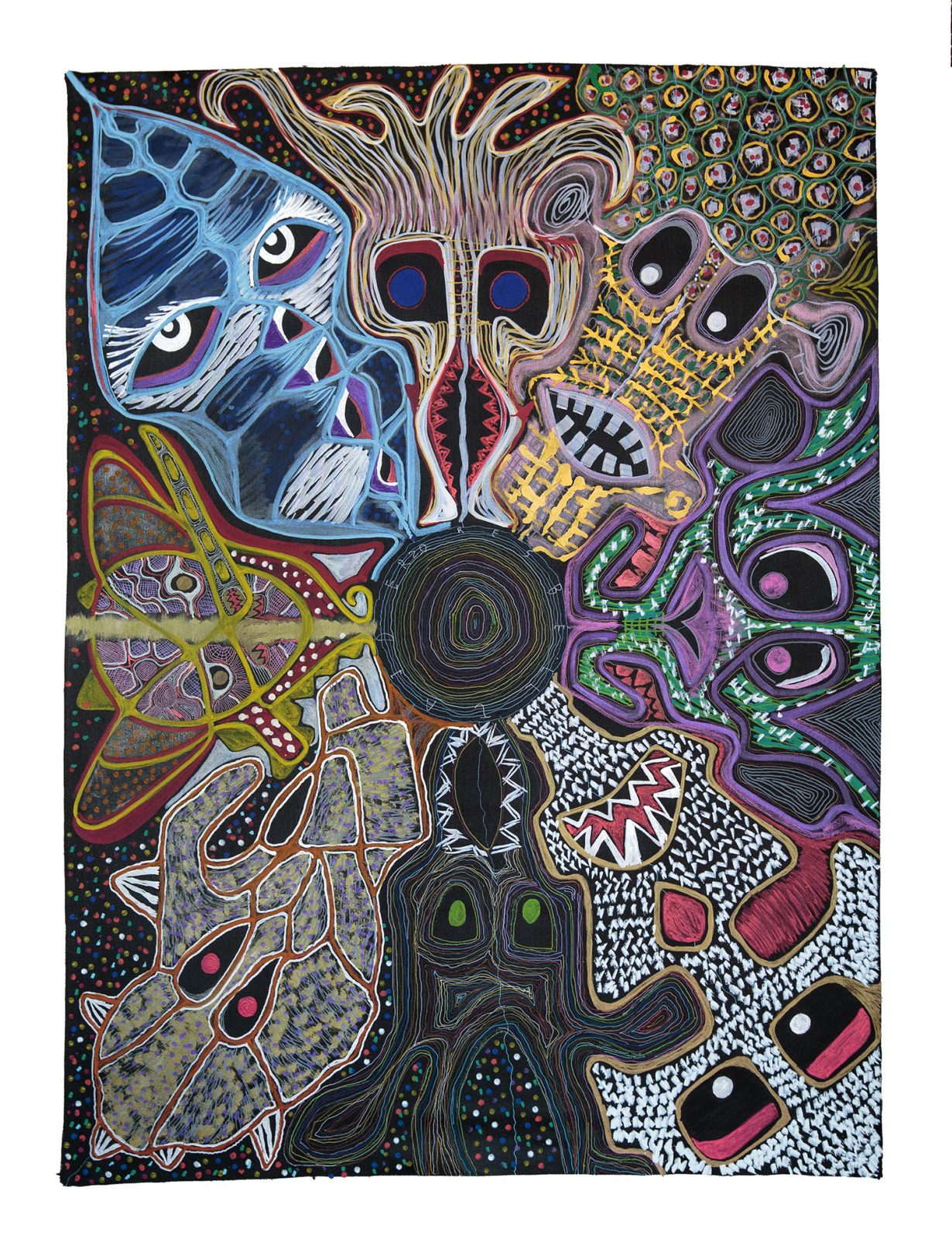

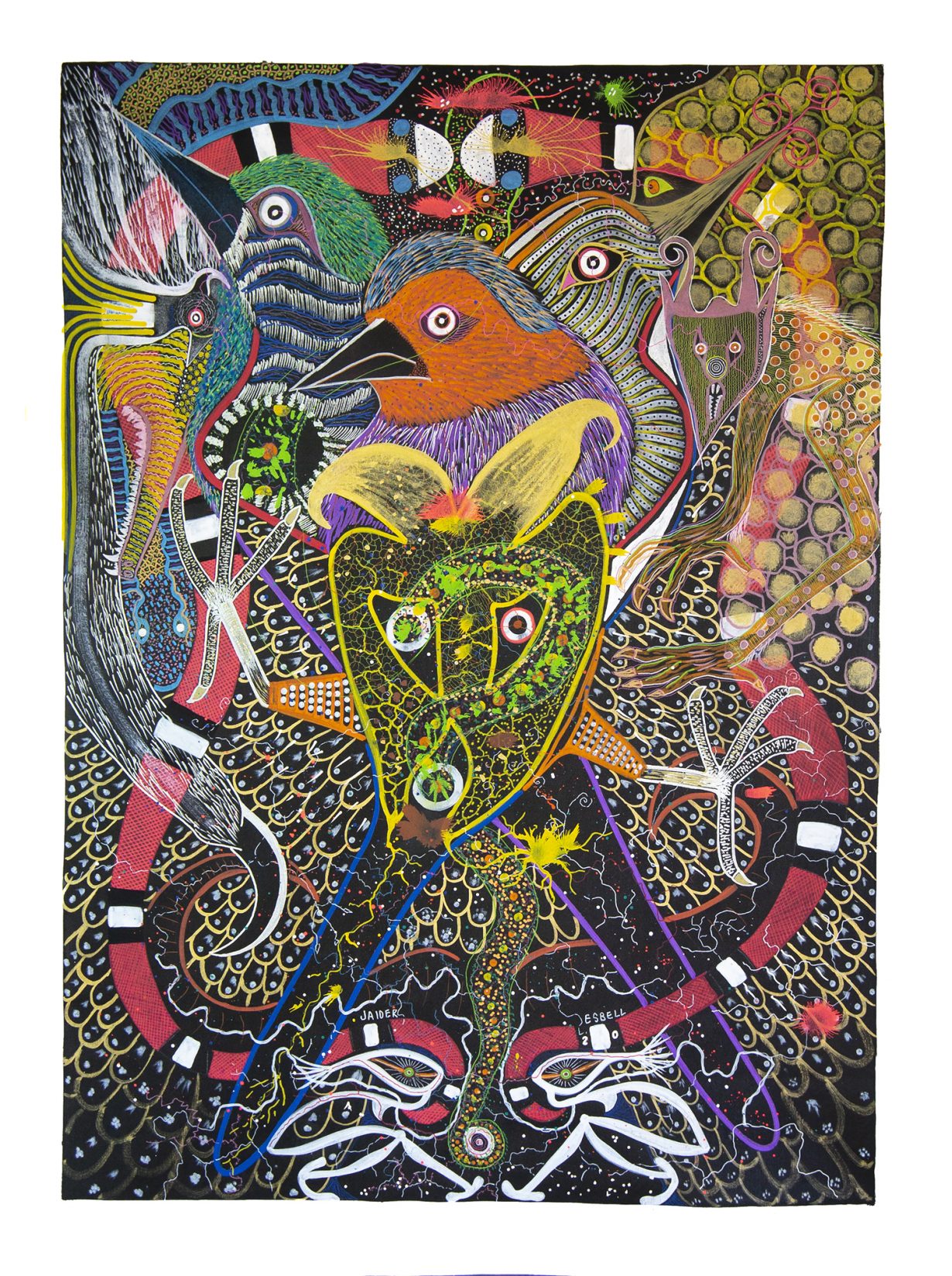

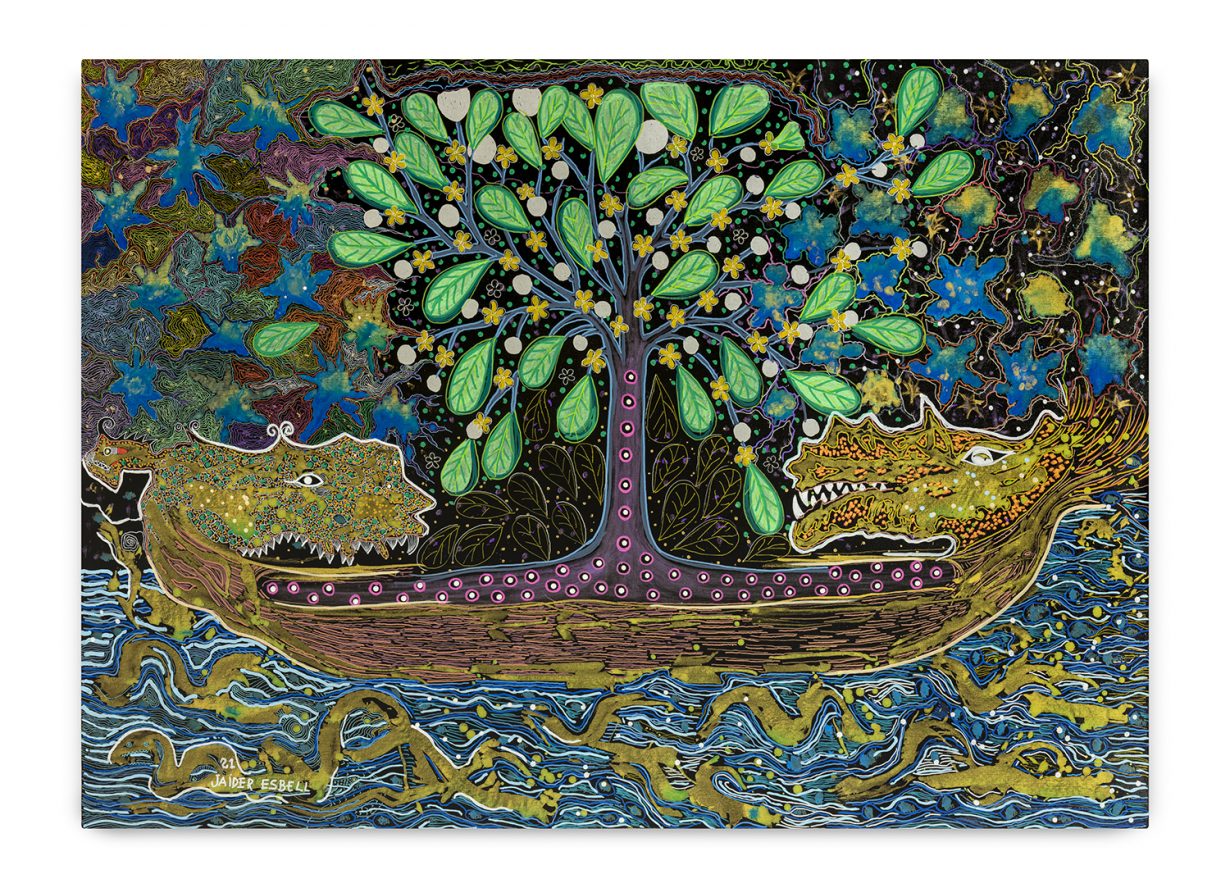

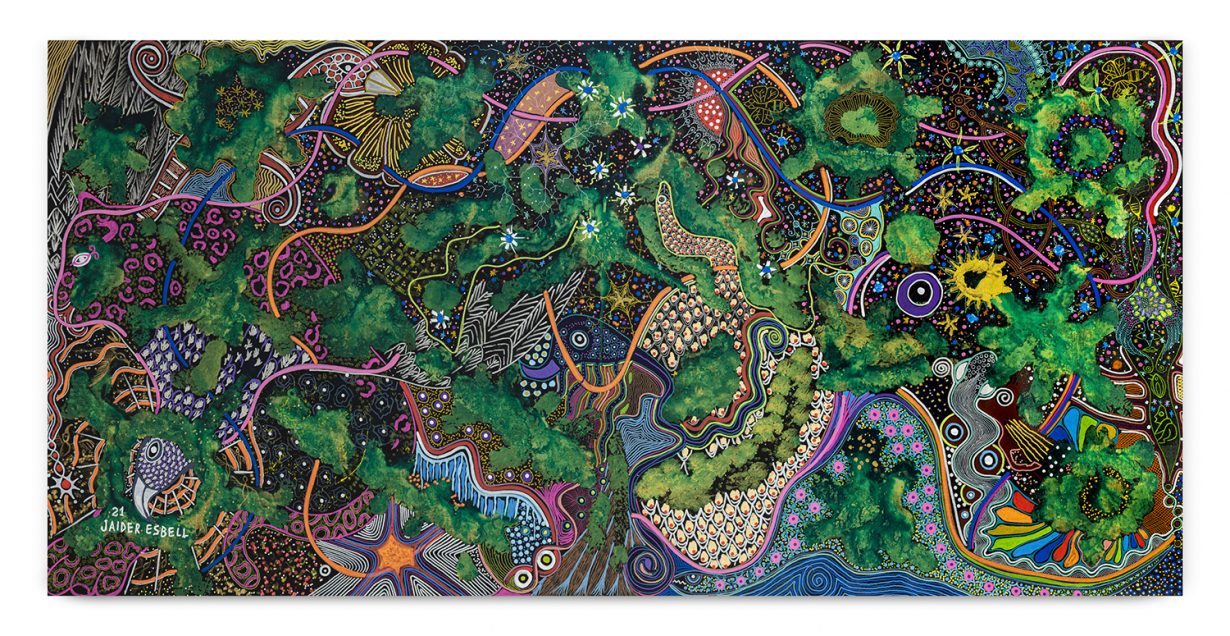

Spanning an entire end wall of the exhibition pavilion is also Guerra dos Kanaimés (War of the Kanaimés, 2020), a long line of paintings by Esbell showing scenes of a forest, the tree canopy drawn with acrylic markers in an exhilarating palette of green, pink, yellow and blue across a black background, the latter a dominant trope of the artist’s work since he began showing regularly a decade ago. The effect is as if this profusion of colour has exploded from the inky darkness. The landscape is populated by creatures: some familiar, some, at least to the European eye, supernatural. Three wolf-like figures stand on their hindlegs, their backs to the viewer. Yet their hands seem human and their plumage – which seems a better description than ‘fur’ – is represented though ornate and detailed multicoloured patterning, more peacock than canine. These figures, tall and hunched and not necessarily friendly in demeanour, are kanaimés, deadly spirits in the tradition of the Makuxi people. Elsewhere in the series, three birds huddle together in a similar formation to the wolves, this time facing out of the painting; another canvas shows a goat-like figure merging with its highly decorated surroundings.

A Guerra dos Kanaimés (detail), 2020, acrylic and pen on canvas, 110 × 145 cm Photo: Marcelo Camacho. Commissioned by Fundação Bienal de São Paulo for the 34th Bienal

A few weeks prior to the opening of the Bienal, and of an Esbell- curated group show of fellow indigenous artists at the city’s Museu de Arte Moderna, we meet in the garden of Galeria Millan in São Paulo. Esbell speaks to me in Portuguese through an interpreter, and we agree he can look at the interview transcription to check the translator’s accuracy. He says that to not have this control or agency with respect to his words would be a “colonial” act and run counter to what his work has been about ever since he started painting: the use of art as a form of pedagogical activism – “artivism”, as he calls it – aimed at giving voice to his own indigenous group and others.

Portal Makuxi, from the Jenipapal Series, 2019, Posca pen and natural genipap ink on paper, 42 × 30 cm. Courtesy Galeria Millan, São Paulo

The latest paintings hark back to one of his earliest works, which shows a baby crowning through the vagina of a woman, its pate black against the mother’s wide stretched legs. “It’s as if that first work also gave birth to a little bit of my self-awareness [as an artist],” says Esbell. “This baby was born during an ecological crisis that involves and affects everyone’s life.” He went on to make a series titled It Was Amazon (2016) which, again in white paint on black, depicts incursions on Makuxi land, the destruction of the forest and the continued attack on indigenous cultures. One work shows a boat shipping off a haul of caged birds, with ‘trafico’ written across the prow; in another, a giant figure wearing a fedora drags several others along by their hair. (‘O explorador’ is written above.) A third shows the forest cleared and littered. “The baby is born in the Amazon but it sees its birthplace, its crib, deteriorated, destroyed,” the artist explains. Esbell moved to the state capital of Boa Vista in 1998 and studied geography at university, before becoming a lineman at the state electricity company. He left the job in 2016. “I started to walk a lot in the world, I met many shamans – pajés, xamãs – from different peoples. And they begin to guide me, to expand my awareness to larger cosmogonic issues,” he continues.

“My masters, the shamans, said ‘art is our knowledge’, it is capable of recreating the world,” in response to which Esbell started introducing colour to his painting. “The black background would be emptiness, collapse, and the small fragment of coloured paint begins to arouse, to promote again the reintegration of life… These paintings, in a way, have the support, the instruction of masters of thought from various cosmologies, who nourish me with these visions through rituals, through ancient practices. And then I, as an ‘artist’, start to do a kind of download, accessing information from this environment, bringing it to our material, everyday nature. In short, transforming it into a ‘work of art’.”

He considers himself to have been an artist ever since, aged six, he first heard the stories of Makunaimî (whom Esbell says is grossly mischaracterised in Mário de Andrade’s 1928 novel of the same name, a founding text of Brazilian modernism). “Makunaimî is our grandfather and at the same time our God. We don’t put God somewhere else, he belongs to the family. We have the same DNA, our blood is his blood. Makunaimî is also the creator of everything we know, a creator of worlds.” He continues: “The creative ability that I bring to my work comes, I have no doubt, from this idea of enlightenment, this ability to reconstitute things apparently from nothing, from the absolute emptiness. From the thing that doesn’t even exist in the material world.”

In the Makuxi tradition, kanaimés can be malevolent – deadly even – or they can come to the defence of those to whom they feel an allegiance. Outside the pavilion, on a lake in Ibirapuera Park, the artist installed a pair of 17-metre inflatable snakes, whose purple-and-pink patterned bodies each end in a pair of red eyes. The beasts are thought to offer the Makuxi protection. They face towards a permanent granite statue commemorating the seventeenth-century bandeiras, the flag-carrying slavers and fortune hunters who ‘discovered’ Brazil’s interior. “The Makuxi people are essentially warriors,” Esbell says. “They have survived to this day because they are warriors. They know how to fight, they know how to make war. A very beautiful war. We fight very well. And one of these days my mother, teacher, said ‘Jaider, go! And take the word of the Makuxi to the world’. I am carrying out an order from the women, from the matriarchs of my lineage. And she heard it from her mother, her grandmother. We’ve always been in politics.”

Esbell runs a self-described ‘laboratory’ in Boa Vista, which shows work by artists from multiple indigenous ethnicities and runs workshops on art and theory. Since 2013, he’s organised the Meeting of All Peoples, a recurring large-scale group exhibition. On the opening day of the Bienal, which came just after the largest ever gathering of indigenous people in Brasilia – a weeklong occupation protesting land rights ‘reforms’ being pushed through the supreme court by the far-right government of Jair Bolsonaro – he and several other exhibiting indigenous artists unfurled a banner declaring it the ‘Bienal dos [of ] Indigenous’. He says he wants to set up an indigenous art ecology that runs parallel to the institutions and galleries that grew out of colonialism and exploitative capitalism. Though he has shown with Galeria Millan, he refuses to be represented by any gallery other than his own. “Artivism is this place for us to take those things that don’t reach the main- stream media, because of machismo, patriarchy,” says Esbell, adding that when the Makuxi voice is heard in the media, “they want to flourish, fantasise and disguise, distort, soften our words. We are in this fight, a fight for life, for territory.”

Yet the artworld, I suggest to him, is also adept at hoovering up good political intentions and exploiting them. The Makuxi, Esbell counters, “could have not given a shit about the world and stayed there in Raposa Serra do Sol. There we have everything. Sun, water. We have millions of diamonds. All our ‘wealth’ is there. But we are not selfish, we are fighting for greater dignity. Which is not only indigenous, it is human. In fact much more than human. We are fighting for the European, we are fighting for the children, the children of the guys who killed our family, because we are of that nature, do you understand? That’s ‘artivism’. It is something that cannot be explained. Call it love, madness, anything, but it’s an energy with which the mother tells us to fight. So, we are not fighting for the maintenance of privileges, which is this mediocre thought that these Brazilians think we have, privileges. We don’t have any privileges. So, for me it is very clear that the urgency is ecological, it is transracial and transgenerational, transcosmological.”

Work by Esbell in on show at Moquém_Surarî: Contemporary Indigenous Art at MAM São Paulo, through 28 November, and the Bienal de São Paulo, through 5 December