A new show at Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry showcases a British working class transformed by first-, second- and third-generation immigration

There was a time when ‘British working class photography’, the subtitle of this exhibition of works by approximately two dozen artists, might call to mind either black-and-white social realism by the likes of Tish Murtha and the work Nick Hedges did for charity Shelter during the 1960s or the kitsch, exploitative camp of the dreadful Martin Parr. Kids would play in postwar bombsites, flat caps would be worn. There would be whippets, closed mines and kiss-me-quick hats on a dismal beach. In these vintage careers it was rare to see a nonwhite face. Curator Johny Pitts, best known for Afropean, his 2019 book exploring Europe’s relationship with Blackness, shows instead a British working class transformed by first-, second- and third-generation immigration; a society not of twentieth-century decline – the works all date from 1989 onwards, the main title, Pitts notes in his introductory wall text, invoking Francis Fukuyama’s neoliberal consensus-championing book The End of History and the Last Man (1992) – but enriched with renewed confidence, despite years of austerity politics.

This is most obvious in those photographs that document the local fashion, music and nightlife scenes. Eight prints hung friezelike of photographs by Ewen Spencer dominate one wall, profiling the dancefloors of UK garage nights at the turn of the millennium. The frenetic sweaty bodies of dancers have ‘the lean’, a wall text by Pitts informs us, which is Spencer’s term for a cocksure attitude. The same might be said of British-Yemeni boxer ‘Prince’ Naseem Hamed, shown in a triptych by Trevor Smith, photographed topless at the height of his fame in 1994 with mirrored sunglasses and glamorous leopard-print shorts. There is swagger too in the grittier photography of Josh Cole, in which stars of his local rap-scene are shown posing on top of cars or in the milieu of inner-city housing estates. Of these cultural documents, Elaine Constantine’s portraits of the Northern Soul music-scene rise most above Dazed and Confused-style editorial work. Steve in his kitchen (1993–96), in which a young dancing man jumps so high he almost knocks his head on the low ceiling, is an electrifying image, the subject caught in a moment of transcendental ecstasy that lifts him far beyond the mundanity of his surroundings.

This is the working class of the big cities, in which grassroots culture sits in close-enough proximity to power brokers (be it hipster media outfits or record labels that are gatekeepers to wider success) that it becomes commodified. With this in mind (and perhaps apt given I saw this touring show in the smaller town of Coventry), the stronger moments are the more intimate glimpses of provincial life Pitts provides: not glamourous boxers, but Rob Clayton’s Resident, Wilson House, Saturday Afternoon (1990– 91), in which a man watches the boxing on his television, enjoying a cigarette (an arrangement of vibrantly dyed indoor pampas grass providing a pop of colour to the otherwise muted palette of the scene); not cool kids out clubbing, but the woman and her two children pictured by Jim Mortram, watching ‘2012s Hottest Dancefloor Hits’ on a music-video channel (the title, Emergency Housing, 2012, provides a clue to the sparsely furnished circumstances). The teenage boy sits on the windowsill, either by necessity, with the small sofa occupied, or by desire for escape.

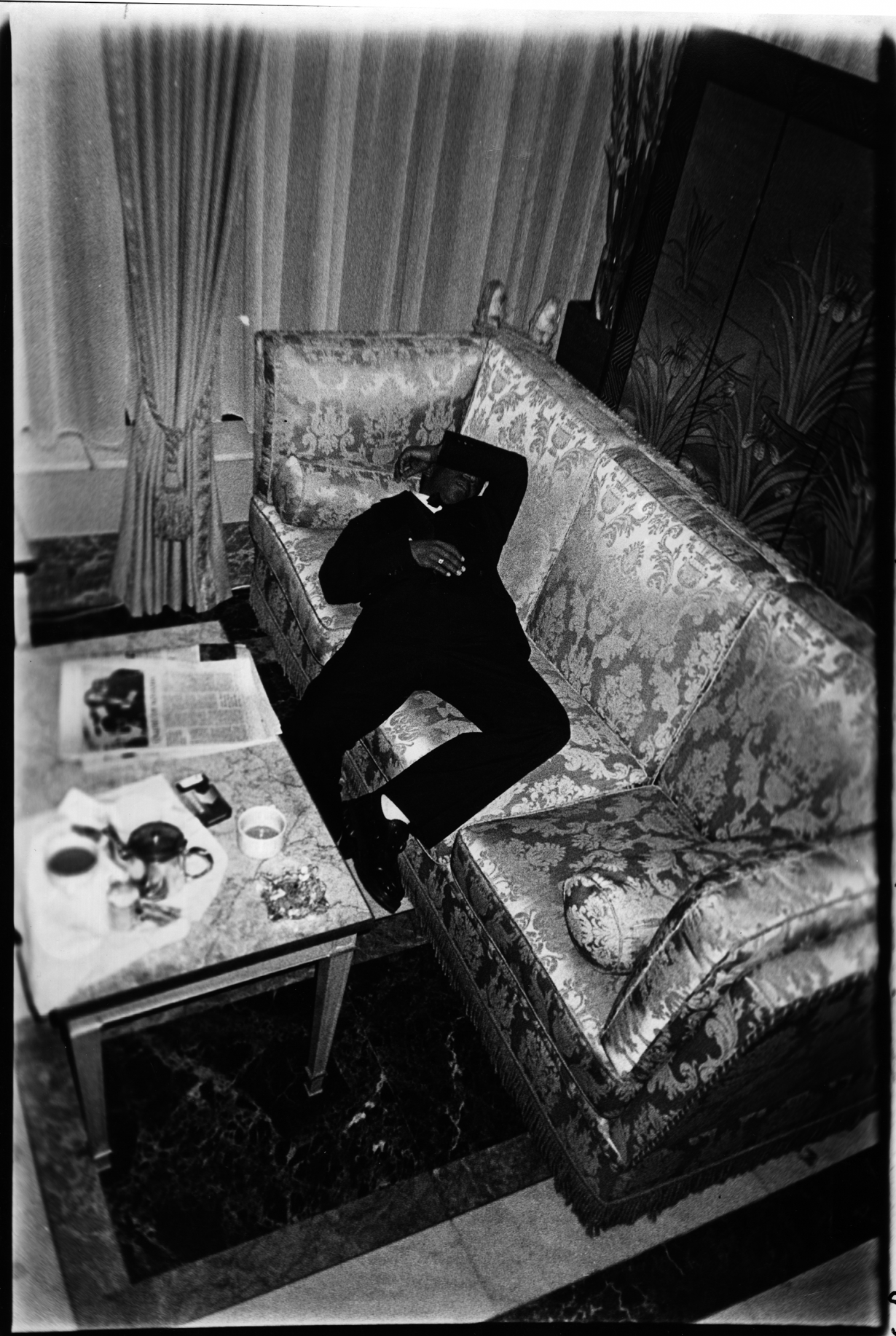

There are moments of cliché in the choices Pitts has made, no more so than when the curator turns his attention to rural life, represented by sheep farmers (in a series by Richard Grassick), fishermen and pigeon fanciers (in work by Joanne Coates). This seems a limited view of employment outside urbanity: where are the Amazon warehouses? Where are the call centres? But these are outweighed by the range of lived experience to which Pitts is keen to give space, a range that’s embodied in the contrast between the emo Asian kid, with blue dyed hair and holding a peacock feather, in Kavi Pujara’s Talitha, Ross Walk (2020), and Rob Clayton’s Shop Proprietors (1990–91), a portrait of the proud Asian owners of a corner shop. Pitt’s choice of title, though useful for signalling the date range of the work, doesn’t point us to any great interrogation of Fukuyama’s thesis. Chris Shaw’s evocative imagery from his time as a night porter – photos of his colleagues, in the shabby backrooms of hotels, scattered with magazines and half-drunk cups of coffee, catching moments of uncomfortable sleep in cramped positions that belie the black- and-white romance of his film stock – offers a stark rejoinder though. They are the standout works here, portraits of exhausting exploitation and graft of a capitalist consensus that, by now, no longer has anywhere to go.

After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024 at Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, through 16 June