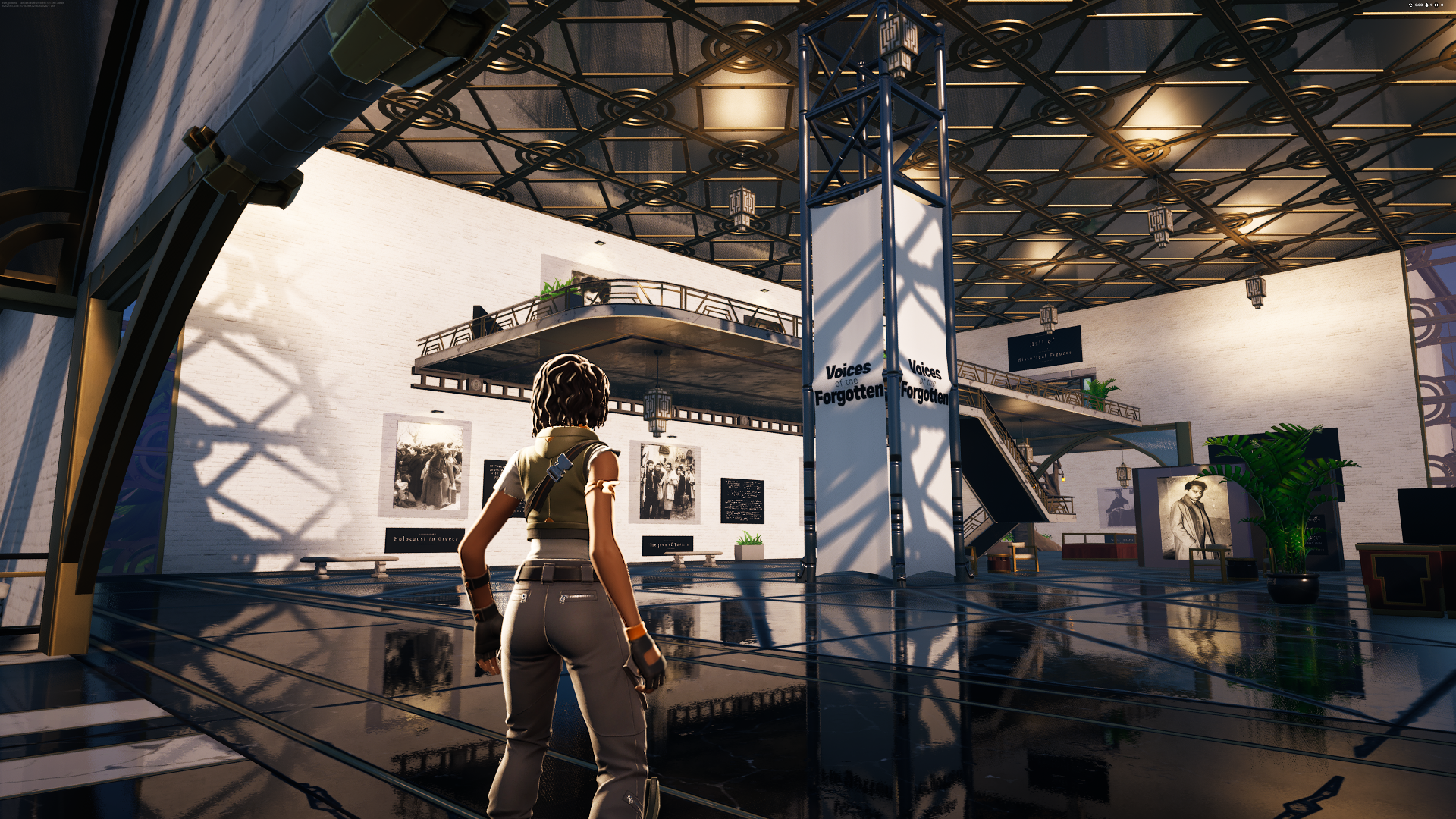

Yes, ‘Voices of the Forgotten’ is a virtual museum in the game’s metaverse-like world

It sounds like the start of a bad joke, or a nightmare vision of the Marvel Cinematic Universe: Spider-Man walks into a Holocaust memorial. In this unlikely scenario, the masked vigilante and his friends Iron Man, Captain America and Thor are confronted with a set of steps leading up to a sleek modernist building of glass, metal and marble. Barely a sound is audible; the mood is, if not sombre, then a little sterile. I press on the right mouse button – an action that usually causes the avatar to aim down the sight of their weapon – to zoom in to get a better view of the various texts: each is intended to teach visitors about ‘the heroes who saved Jewish lives during the Holocaust and also the Jewish members of the Resistance’. Spider-Man cranes his neck upwards before looking around for his companions. They seem to have vanished into thin air; they must have already logged off.

A few weeks ago, game maker Luc Bernard opened the doors to his virtual Holocaust museum in the online multiplayer video game Fortnite (2017). This isn’t the first time that educational material has arrived on Fortnite. In 2020, an official partnership between Epic Games and Time Studios (affiliated with Time magazine) yielded a Martin Luther King experience which allowed players to make their way through Washington D.C. while viewing images from the Civil Rights Era and listening to King’s seminal ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. Bernard, though, seems to have learned from the mistakes of that effort which facilitated strange, dissonant moments like Rick (of Rick and Morty) and Superman dancing in front of a screen showing the famous speech. In the Holocaust memorial, titled ‘Voices of the Forgotten’, there are no emotes, no dancing and no shooting, yet that doesn’t make the experience any less bizarre.

What’s striking about ‘Voices of the Forgotten’ is its lightness where equivalent experiences in the real-world would seek to inspire heaviness. Because the event is happening in private rather than publicly – alone on a machine with possibly a few digitally connected friends – there is no sense of a collective atmosphere impressing itself on the body, no external pressure to reflect. It feels distinctly ethereal, as if untethered, perversely so, from the earth.

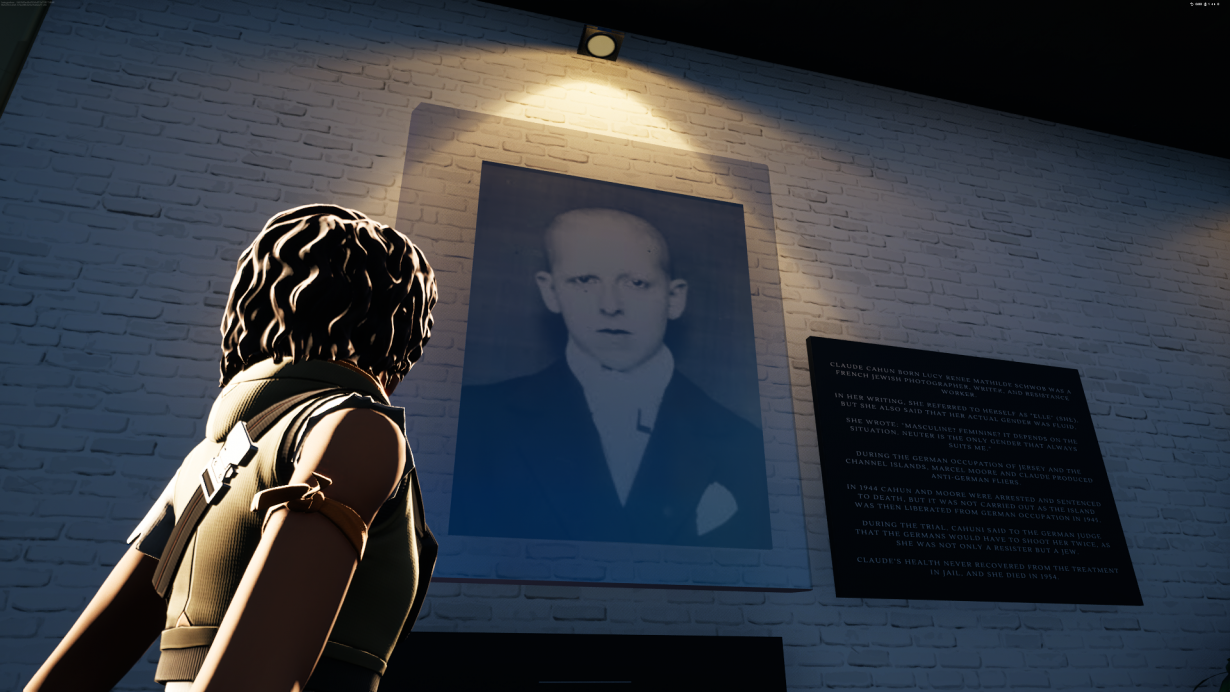

My avatar defaults to a run so I find myself dashing from plaque to plaque as if I were soaking up the exhibition against the clock, reading at the accelerated speed of my digital avatar’s locomotion. Some of these text entries – about photographer, sculptor and writer, Claude Cahun, for example – are cribbed directly from Wikipedia, unadorned prose detailing Cahun’s work with the Resistance dropped into this strange, cartoon world. Mostly, though, the lightness feels as if it stems from how the experience is accessed – via a high-speed internet connection with a package of executable code. It’s an example of what sociologist John Tomlinson calls ‘information immediacy’ (as opposed to a ‘heavier’ machine speed). If information immediacy is characterised by an ‘imminent closeness’, writes Nathan Jurgenson in The Social Photo (2019), then it can perhaps also be defined by an ‘immanent distance’. That’s to say, I was able to exit the experience just as quickly as I was able to enter it; the Holocaust memorial was a fleeting occurrence in the wider universe of Fortnite.

Experiences that defy the normal rules and norms of Fortnite are set to become more common. Previously, an experience in Fortnite must have either been created by the maker of the game, Epic Games, or an official partnership. ‘Voices of the Forgotten’ is part of a new effort to open up the creation of virtual worlds in Fortnite to external game makers. The initiative promises to make the jumble, mash-up aesthetic of Fortnite even more chaotic. The cartoon visuals, a canny bit of design, lend themselves to such an approach: undemanding, generic, chunky yet capable of rendering the kind of detail that fans demand of their favourite characters. The game world is thus uniquely ameliorative to outside phenomena: Travis Scott; Christopher Nolan films; Star Wars – anything that, up until now, had the capital to ink a marketing deal with Epic Games.

These new creator tools will make Fortnite resemble a social media platform even more than it already does, catalysing a new era of user-generated video games. Roblox (2006) already has robust user-creation tools; so does Grand Theft Auto Online (2013), the online multiplayer version of the blockbuster crime franchise, which just acquired a modding company that should make them even more robust. Previously, user-generated content (called mods, short for modifications) occupied a legal grey area for these game companies (sometimes tolerated, sometimes not) but that’s not the case anymore. It’s part of a new drive that aims to keep players plugged into their servers, monopolising their attention and wallets, providing a slurry of perpetual content.

This vast deluge of material is provided by a nebulous group of creators, both hobbyist and professional, some academics would call ‘playbourers’. These people will have to reckon with what most of us already experience on a day-to-day basis. ‘More and more of the world comes to be seen through the logic of what can be digitally captured and shared,’ Jurgenson wrote of traditional social media platforms. ‘The question shifts from what to document to what not to document.’ With ever-greater portions of the real world being scraped for the digital one, not just on social media platforms, but for portals within portals, as in the case of Fortnite, incongruences of the kind that ‘Voices of the Forgotten’ has produced will likely become more, not less, pronounced. They will become weirder and maybe more interesting, perhaps surpassing TikTok as sources of unfettered surrealism.

The surrealism of this Holocaust museum is twofold: its dissonance in the game world of Fortnite while simultaneously reinforcing its strange, anything-goes logic; and how, despite the best intentions of its creator, this kind of logic could contradict, or at least undermine, the idea of how we commemorate the Holocaust. Yehiel Dinur, a writer who was a prisoner at Auschwitz, famously wrote that the concentration camp was ‘another planet’, as if it existed beyond the realm of human responsibility. In its own way, ‘Voices of the Forgotten’ feels like another planet, a virtual one, sure, that also appears to occupy a different moral universe. The museum is a flippant, unserious, copy-and-paste exercise, turning horrifying histories into little more than a symbol of seriousness – a vague gesture towards it.

Lewis Gordon is a UK-based writer on technology and culture. His writing has appeared in New York Magazine, The Verge and The Nation, among others.