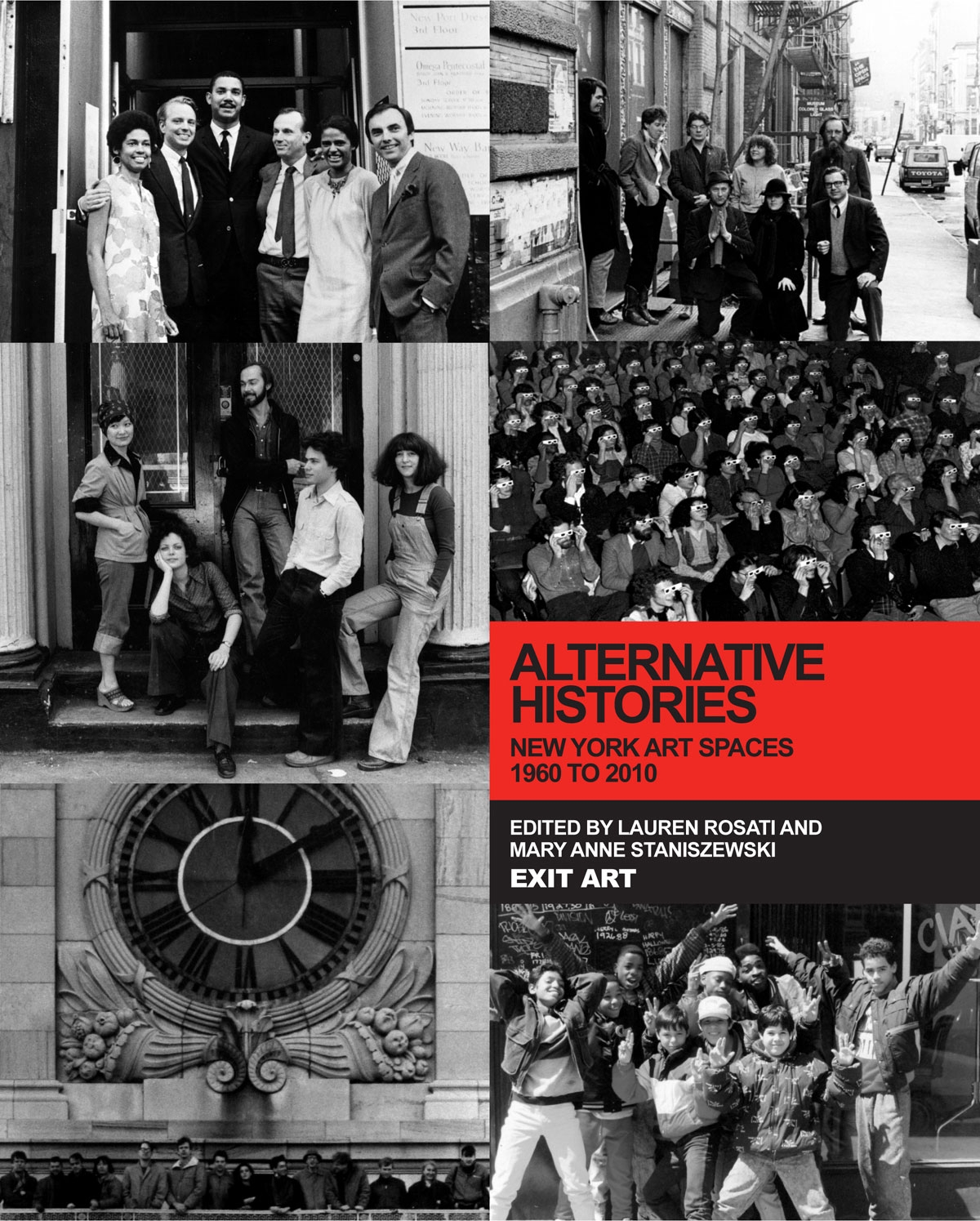

In the introductory essays and interviews to this directory of New York’s historic artist-run ‘alternative’ spaces, the midtwentieth- century artworld comes across as a different planet. While the politically active practice and presentation of art today is the exception to the rule, to judge from the quotes and manifestos that pepper the plethora of material here – the authors of which include artists Papo Colo (who cofounded Exit Art), Jacki Apple (who was behind a number of grassroots spaces in the 1970s) and composer Rhys Chatham – it was central to the creation of a scene that was not only largely anticommercial and anti-institutional, but also engaged in a wider social and political activism. While the book, a catalogue that expands on the themes laid out in a 2010 exhibition at Exit Art, profiles 140 artist-run spaces whose active years range from 1928 (the Sculpture Center, formed in artist Dorothea Denslow’s studio) to 2010 (Our Goods, ‘an online bartering network that supports artists’), its main portrait is of 1960s and 70s frustration and idealism.

The convergence of a general mistrust of government in the wake of Watergate and the first sale of a contemporary artwork for more than $100,000 (at the 1973 auction of the Scull collection) saw artists seeking alternative modes of presenting and experimenting with the process of art’s presentation outside the museum or the commercial gallery. The latter had ‘the goal of self-perpetuation, not experimentation’, writes onetime Exit Art curator Melissa Rachleff.

The reaction against the commercial model included the formation of 112 Workshop (precursor to White Columns), the Kitchen, Artists Space and Creative Time. A number of spaces redressing the neglect by the art establishment of particular sectors of society sprung up too. A.I.R. was a cooperative gallery formed by a group of women artists; Taller Boricua promoted a Puerto Rican voice in art; and Nyumba ya Sanaa gallery was aligned with the Black Power movement. The artists behind these ventures invariably sought to integrate the process of their art’s production into the local community, forerunning the educational remit of all publicly funded spaces now. It’s in an engrossing read, occasionally overly nostalgic, sometimes rightfully pessimistic about the current careerist trends in self-initiated artist and curatorial projects.

This article was first published in the January & February 2013 issue.